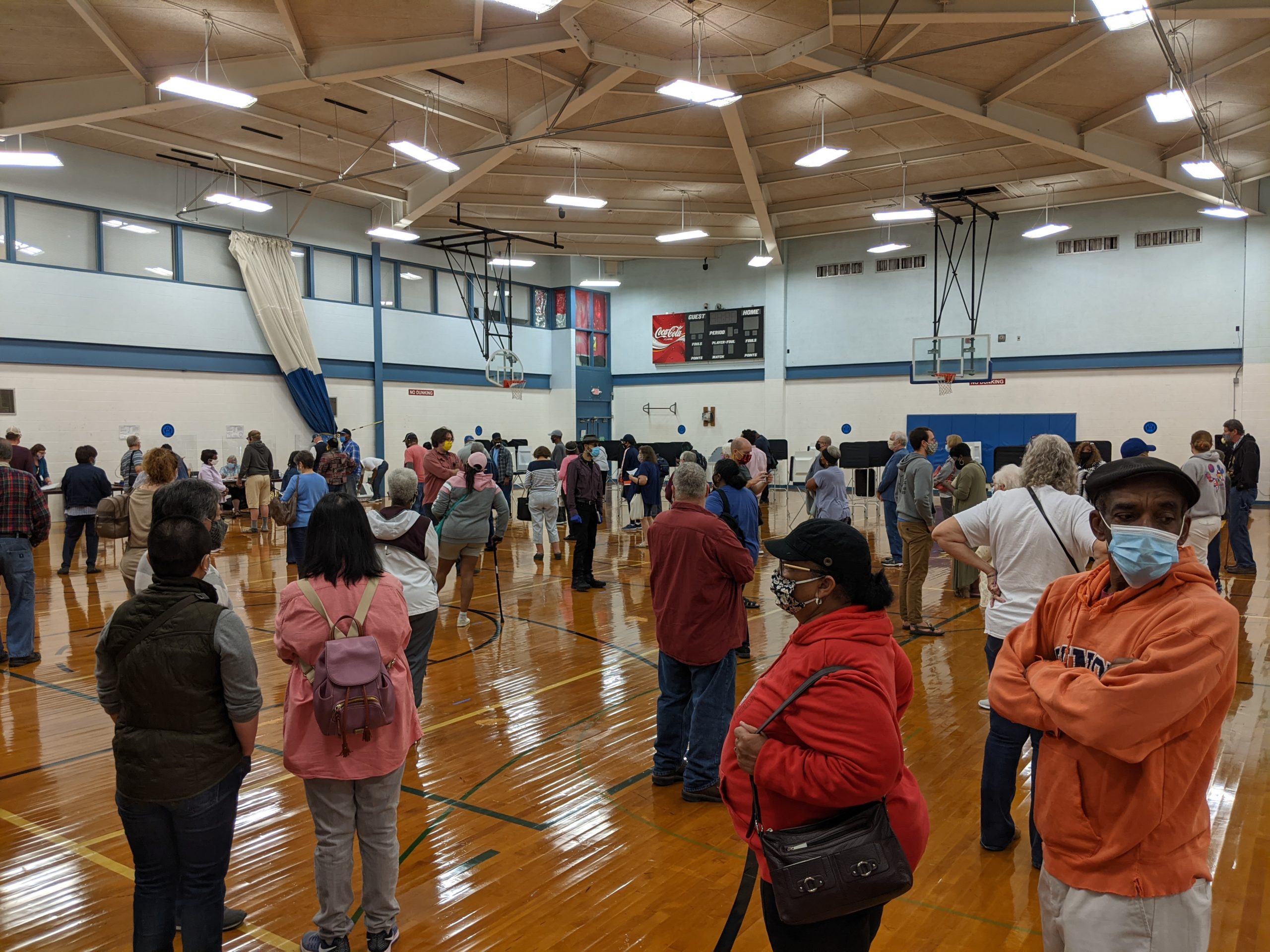

Polls have been open for early voting for about 45 minutes. The room is pretty full, but everybody is masked and keeping proper social distance.

Polls have been open for early voting for about 45 minutes. The room is pretty full, but everybody is masked and keeping proper social distance.

Seven-spotted ladybug (Coccinella septempunctata), observed in our local prairie.

Since spring I’ve been using some workout plans put together by Anthony Arvanitakis. For eight weeks from late May to early July I did his Superhero Bodyweight Workout, and since then I’ve been following along with bodyweight workouts he’s been sharing for the summer.

One limitation that I’ve had all this time is that I haven’t been able to do the hill or stair sprint workouts that he suggests, due to a lingering foot injury. After repeatedly resting my sore foot until it was nearly all better, and then trying to get back into running, only to have my foot start hurting again, I finally took a full month off. That was enough for my foot to finally feel entirely better, so last week I went for a 3-mile run as a test. My foot didn’t hurt during the run, but was sore again that evening and the next day.

I took another week off from running, and then today decided to try a different tack: Those hill-sprint workouts.

Three things about this make it make sense to me:

Putting those things together makes me think that maybe hill sprints will let me run at least a little without aggravating my foot injury.

Another thing I’m doing is extending my warmup quite a bit. I did my full dynamic stretching routine before heading to the workout location. Once I got there I scrupulously followed the prescribed warmup routine, jogging up the hill at 50%, 60%, 70% and 80% intensity (I actually did 5 preliminary jogs up the hill, at gradually increasing intensity). After each of the last two warmup jogs I did a set of 12 straight-elbow push ups (what I call rhomboid pushups) as preparation for the pushup part of the workout.

The main workout then was 4 sets of sprinting up the hill at 90% intensity, walking down, and then doing as many pushups as I could do with perfect form (I did 10, 10, 8 and 8 pushups).

I also did something I’ve always resisted in the past: I drove to my hill. (This being central Illinois, hills are few and far between. My hill is at Colbert Park.) Usually I don’t like to drive somewhere to get exercise—why not walk or run and thereby get more exercise? But with my sore foot, that much extra running would definitely aggravate the injury. Even walking that far might be an issue.

One thing I need to be careful of is to be sure to get in my full wrist warmup. I’m pretty good about that ahead of a rings workout, but perhaps wasn’t as scrupulous as I should have been this time. But the pushups put enough stress on the wrists that it’s good to get them fully warmed up even before the rhomboid pushups.

I’m pretty pleased with my workout. My foot (really my ankle) is a bit tender this evening. We’ll see how it feels tomorrow. On the schedule I’m (tentatively) following, I’ll be doing hill sprints again Monday. If my foot is completely pain-free at least several days ahead of that, I’ll proceed with that plan.

Remembering that @limako really liked @UplandBrewCo CoastBuster, when I saw another of their “side trail” beers—Viking Slang, an Imperial Nordic-Style IPA—I had to pick up a 4-pack. Sharing a can with @jackieLbrewer.

For years I heard the lyrics of the Rolling Stones song “Black Dog” incorrectly. I thought it was:

I don't know, but I've been told

A beetle-age woman ain't got no soul

The main problem here, of course, is that I have no idea what’s meant by “beetle-age.” I mean, is it the lifespan of a typical beetle? Or is it the whole epic since the appearance of the order Coleoptera? Or, for that matter (given the date of the song) is it something about the “Age of the Beatles”?

I was puzzled for years.

I recently added the song to my workout playlist, so I’ve been listening to it more lately, and I’ve realized that I had misunderstood the lyric. It’s actually:

I don't know, but I've been told

A beetle-egg woman ain't got no soul

This makes a lot more sense.

Just sharing this for all the other people out there puzzled by song lyrics. We should have a support group or something.

Kindred spirit. (Although for me it was taiji that started it. So many people stand around with their hips thrust forward and their shoulders internally rotated.)

“If there is a downside to studying MovNat, it’s that I can’t help but watch and analyze people to see how well they move. It amazes me how many people I encounter with a bad back that I end up explaining the hip hinge to, and I seem to talk about glutes a lot these days.”

Jackie was fixing blue-corn pancakes with maple syrup for breakfast, and eating that many carbs first thing in the morning can be a problem for me. However, I have come up with a strategy for dealing with it: Getting in a pre-breakfast fasted workout. My theory is that by doing this I deplete my muscle glycogen, so that my muscles are primed to soak up all the carbs I eat, minimizing the degree to which the glucose spikes my blood sugar.

I have no data to show that this works, but anecdotally I can report that it seems to help.

I’ve been wanting to go for a run. I had planned to go for a run yesterday, but it ended up being rainy enough that I decided to postpone the run for a day. So I might have gone for a run for my pre-breakfast workout, but Jackie was hungry early, and I didn’t want to delay breakfast by an extra hour.

So, I did what’s becoming my standard HIIT workout: I warm up with 3×25 Hindu squats, and then I do 3×25 kettlebell swings with my 53 lb kettlebell. It’s a quick workout—it’s all done in 20 minutes, including some amount of pre-workout warmup—and it’s of high enough intensity to burn off plenty of glucose.

After breakfast (and a bit of digesting) I went ahead and got out for my planned run. After the persistently sore foot I’ve been dealing with for months now simply refused to get better, I had taken a full month off from running to see if all I needed was plenty of rest to fully recover, and that may have done the trick—I went out for a 3.33-mile run, and I had no foot pain whatsoever.

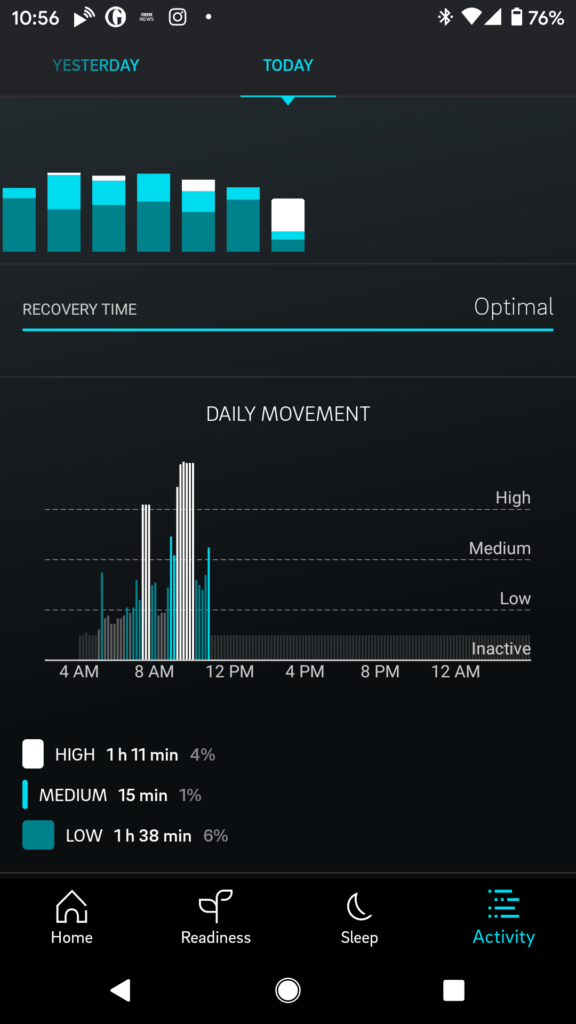

I don’t wear my Oura ring for the kettlebell workouts (or other workouts where I have to grip something, because handles, bars, and (gymnastic) rings don’t play well with the Oura ring). However, my Polar heart rate monitor will tell Google Fit about my workout, and the phone app for the Oura ring will read that data and give me credit for what I did while the ring was off:

My peak heart rate during the kettlebell swings would have seen me to much higher activity levels than the just-barely “High” levels shown, but that’s because it’s an interval workout. A set of 25 swings takes me just about 50 seconds, and then it takes about 3 minutes for my HR to drop low enough that I can do another set. The software is averaging those periods together. Unless I’m doing sprints (which I didn’t today) a run is just a steady-state effort. I try to keep my HR down in the MAF range, but didn’t manage it today (because of the prior HIIT workout).

Exactly why I quit using Facebook too:

“Life is too short to wade through idiotic Jordan Peterson videos so I can feel depressed about how many people I know from high school are now openly racist.” — Facebook is setting fire to America by @ryanlcooper.

One thing I’ve started doing (without really thinking about it until just today) has definitely improved my life: I’ve changed my attitude about “saving” energy for later.

It used to be that I’d consciously do less, if I expected to need that energy later. (And not just with energy. I’d ration all kinds of things that I had in limited supply. When I was suffering from plantar fasciitis, I’d ration my time spent standing or walking.)

I do much less of that now. It’s not that I have boundless energy, but I’m consciously refraining from setting boundaries in advance: I treat my energy as if it were boundless—and then, only when I find that I’ve become very tired, do I go ahead and quit spending energy with reckless abandon, and prioritize recovery.

One key here is having come to understand how important that second step is. I deplete myself, and then I recover. The more I do both of these things, the better I feel.

Children are like this—boundless energy and then none. (It was somebody pointing this out that prompted me to recognize that I’d shifted in this direction myself.) Broadly speaking, natural systems often work this way. A grassland that is intensively grazed and then allowed to fully recover tends to be healthier, more productive, and more diverse than one that is perpetually grazed, or one that goes ungrazed for long periods of time.

I recognize that I have some privilege here. I’m in a position where, if I tire myself out, I can just decide to stop whatever I’m doing. Someone working on a chain gang (or in an Amazon warehouse) doesn’t have that same option. If you’re not in control of when you stop, acting like you had boundless energy could get you into real trouble.

The guy behind the superhero bodyweight workout plan I followed for 6 weeks from late May until early July lined up some superhero t-shirts participants could buy, and I got one of the Captain America shirts.