It’s been eleven years since I retired, at age forty-eight.

I hesitated at first to call it “retiring early,” even though in my head that’s exactly what I was doing. Partially that was because I hadn’t decided to take the plunge. I had been intending to retire early, doing the planning, doing the saving. But part of a proper early retirement is deciding that you’re ready, based on having established an income stream that covers your expenses.

I hadn’t done that. What I did was learn that my employer was closing down the site where I worked, and then wing it. I counted my money; I did some figuring. I secretly figured that I could retire, but I didn’t tell people that. What I told people was that, “Although I couldn’t retire, I had reached the point where I didn’t need to work a regular job any more.”

I’d meant to celebrate the 10-year anniversary with a post about how things had gone, but haven’t gotten around to it. And I guess this isn’t going to be that post either, because I’ve gotten so annoyed by an ignorant article by Jared Dillian in Bloomberg Opinion, The ‘Radical Saving’ Trend Is Based on Fantasy—which manages to both be wrong about the facts, and (more fundamentally) miss the whole point—that I’m compelled to write a response.

Dillian’s item number one manages to be both wrong on the facts and miss the point in roughly equal measure:

Most people save now because they want to consume later. But the FIRE folks don’t want people to consume. For the FIRE folks, the point of saving is simply not to have to work. To give you the freedom to do whatever you desire over the last 50 years of your life. Trouble is, the freedom to do anything you want isn’t much fun when you’re hemmed in by a microscopic budget.

First of all, the “financial independence/retire early” (FIRE) folks do want to consume. It’s just that they’ve figured out that, at some point, just consuming more doesn’t make your life better. Rather, they’ve thought deeply about what they need to consume to make themselves happy, they consume that, and then they stop consuming.

I think of it as drawing a line under the stuff that’s worth paying up to get all I want of exactly what I want, and then paying zero for the things that don’t make the cut. (Most people don’t do this. Instead of a cutoff they have a gradual trickle off, spending smaller and smaller amounts as they work their way down the list of things they want. This is no way to be happy. The money they’re spending on stuff they only kinda want eats into the money they could be spending on the stuff they really, really want.)

Second, the whole point of FIRE is not to “simply not have to work.” Rather, the point is to free yourself to do whatever work you want, instead of whatever work pays best. Everybody I know who’s retired early still works at something.

This point is made very clearly by literally everybody I know of who has written about FIRE. To miss it suggests either that Jared Dillian was very careless indeed in doing his research, or that he is willfully missing the point.

Third, it’s simply false to say that “the freedom to do anything you want isn’t much fun when you’re hemmed in by a microscopic budget.” Rather, the freedom to do anything you want enables you to do the most important thing you can think of.

Maybe the most important thing you can think of is really expensive (in which case you’d have saved a lot of money to fund your retirement). But very likely the most important thing you can think of is free, or cheap, or even modestly remunerative. (The list is endless—crafting musical instruments, researching obscure topics in your field you didn’t have time for while working full time, helping care for a family member, documenting the history of your ethnic group, researching the natural history of your region, working for a candidate or a political party or a non-profit that’s trying to stop global warming or child trafficking or hunger or poverty…)

Finally, who says your budget has to be microscopic? Rather, your budget should fund your planned expenses. If the most important thing you can think of is to take a round-the-world cruise every year, you’ll want to save more money than someone whose most important work is to study the local mosses.

I’m going to skip over his second item, because he just makes the same mistake again, imagining a purpose of being able to “consume more later” is a better justification for saving than being able to live exactly the life you want to live and do your most important work.

His third item manages both to make the same mistake yet again, and to insult everybody who understands the difference between the most important work you could do and the work that pays the most:

What is wrong with working? Why do the FIRE people dislike working so much that they want to quit at age 35? Working gives people purpose… I have had unpleasant jobs, and even working an unpleasant job is preferable to not working at all. I am one of these people who thinks there is dignity in working, that every job is important no matter how small.

(I left out a random swipe against basic income.)

I don’t know any FIRE people who dislike working. I know a lot of FIRE people who dislike working at regular jobs. I know a lot of FIRE people who dislike working for psycho bosses, bosses who take inappropriate advantage of them, and stupid bosses who don’t know how to do their job well. I know a lot of FIRE people who think there is great dignity in choosing to do whatever they think their most important work is, regardless of whether it pays enough to live on.

I’ve worked at bad jobs now and then. Not unpleasant jobs, which are okay as long as the work is worth doing. But some jobs are not worth doing.

One example: a manager one place I used to work put huge pressure on employees to finish a task, despite knowing that the project the task was for had been canceled —because completing the project on-time was required for the manager to get a big bonus. That is work that was not worth doing. (Literally. It produced nothing of value to the company, while keeping the employees from doing something that would be valuable.) That sort of situation, which is more common that you might think, is what FIRE people are trying to escape.

Finally, Dillian suggests:

The biggest issue with the FIRE movement is that it’s the ultimate bull market phenomenon. FIRE seems to work because the stock market has gone straight up. A bear market will change that. Even if stocks do return 8 percent to 12 percent over time, it’s not going to be any fun living on a shoestring budget and watching your nest egg decline in value by 30 percent to 50 percent.

Here I have actual first-hand experience. My early retirement started in the summer of 2007, and pretty much right after that came the financial crisis in which my stock portfolio lost about 40% of its value.

I engaged in some pretty dark humor during those first two years, joking about how I wouldn’t want to be retiring early in that kind of market.

In fact, I was just fine. I did the obvious things: I found a way to earn a little money (in my case by writing, which was what I wanted to do anyway), and I got a little extra frugal (on a temporary basis, to preserve my capital).

So, yes, I did live on a “shoestring budget” for a few years while watching my nest egg decline—although not by as much as 30%, even though the stock portion lost 40%, because the bond portion soared and the cash portion remained stable (although the income it produced declined).

Contrary to Dillian’s concerns, it was actually great fun. I was writing full time—fiction in the mornings and articles about personal finance and frugality for Wise Bread in the afternoons—which was exactly what I wanted to do. We didn’t travel much, and we didn’t buy much in the way of new clothes, but we were very happy.

Since then my portfolio has more than recovered. Part of that was just the bull market. Part of it was basic portfolio re-balancing, which automatically had me sell bonds near the peak and buy stocks near the bottom.

After all, the 4% rule (which I assume is what Dillian is implicitly rejecting) was never a law of nature. It’s always been just an empirical guideline. The FIRE people all understand that you can’t just “set and forget” your spending. Instead you need to pay attention, and adjust as needed. Maybe you need to spend less. Maybe you need to find a way to earn a little money. I did both those things, although not very much of either one.

For eleven years now I’ve spent every day doing exactly what I chose to do.

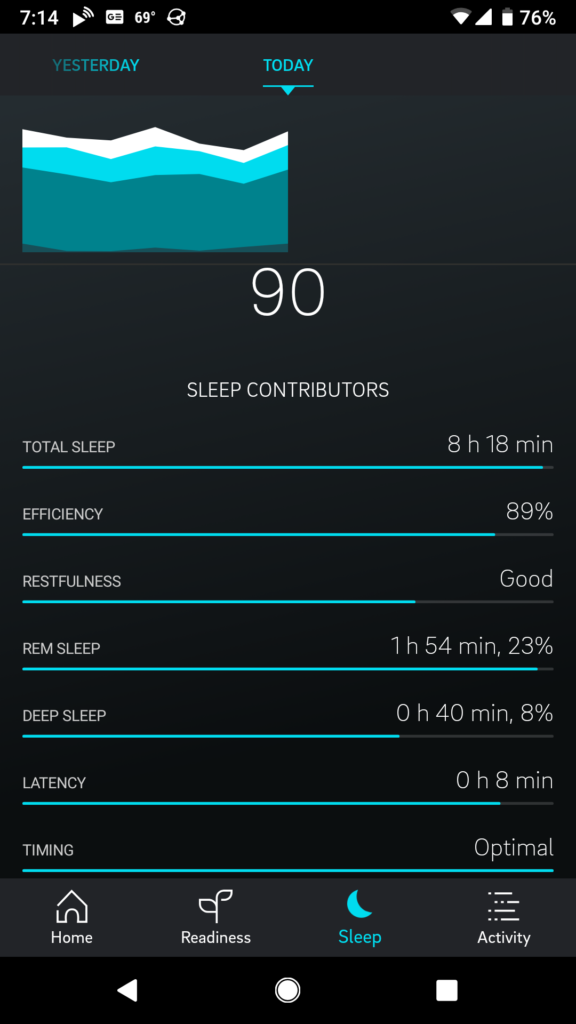

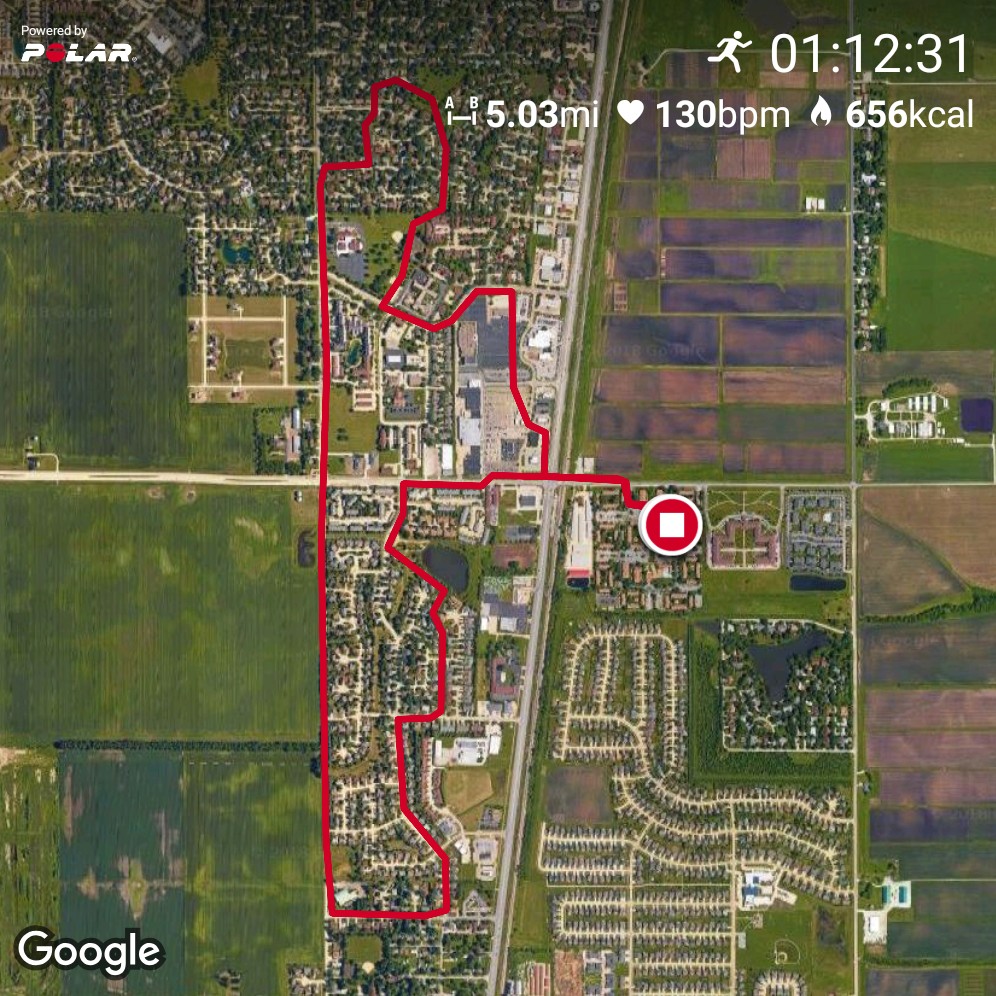

What I chose to do has varied, of course. At first it was all writing. When I realized that I wasn’t taking full advantage of not needing to be at my desk during working hours, I rearranged my schedule so I could spend more of the daylight hours engaged in outdoor exercise. I took a taiji class, discovered that I really enjoyed the practice, and persisted with it. Now I teach taiji, and it has become one of those modestly remunerative things I was talking about.

But for eleven years, it’s always been whatever I most wanted to do.