Thanks to Srikanth Perinkulam for the very useful worked example of Self-hosting Jitsi video conferencing. Like everyone, I’ve been spending too much time in Zoom and Google Hangouts, and am looking for a secure, open alternative.

Tag: open source

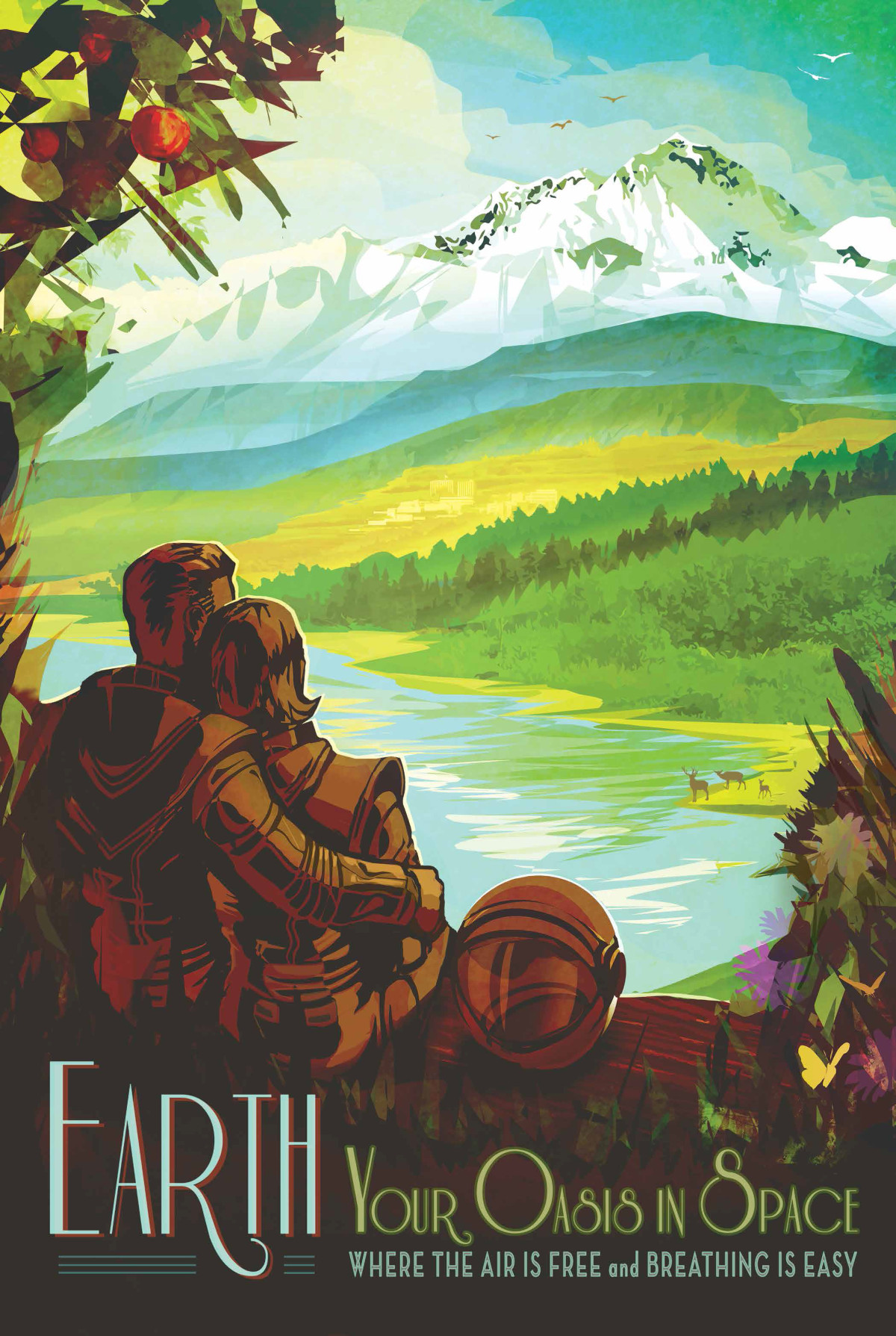

NASA (space) travel posters!

I’m both a huge fan of poster art and a huge geek about travel to fantasy locations, so I’m doubly entertained by this batch of posters from the fun-loving artists at NASA advertising a bunch of possible travel locations in our solar system and beyond, available in resolutions high enough for printing at poster size:

Source: Visions of the Future

Image courtesy NASA/JPL-Caltech.

Open Source Fiction?

Frank Gilroy, a guy I used to work with at Motorola, has written a post called My Thoughts on Open Source Story Telling about why he’s putting his fiction up on the web. I had a few thoughts on the topic that I would have shared in a comment, except that he’s got comments turned off. So, instead here’s the long version.

To begin with, fiction was always “open source” in the sense that you can’t keep the text secret from the reader. In this way it is unlike software (where you can keep the source code secret from the people running the program). Because of this, in software “open source” was an important (and somewhat transgressive) notion. In fiction, though, it’s just the way things have always been.

Since fiction has always been open source, stories have always been pieces of a greater conversation. Some explicitly respond to other stories, but even the ones that don’t are informed by what the author has read. At least as important, the readers’ reactions are informed by what they’ve read, whether or not the writer has read the same things.

It’s rare in fiction for writers to do what’s common in open source software—use their access to the source to improve it (fix bugs, add functionality, improve standards compliance, and so on). But the reason has nothing to do with a lack of access to the text.

Putting that issue aside, the remaining issues seem to be money (how does the writer get paid) and access (how does the reader find the work).

Money

In software, the open source model offers a revenue stream for providing support. Is there an equivalent for open source fiction? Perhaps one could say that some professors of English and literature do, in a sense, get paid to support the readers of open-source literature. But I don’t see a business model forming around the idea that a writer would publish his stories free on the web and then charge a fee to explain them.

Why do people ever pay for fiction? They pay to be entertained, to be edified, to be amused, and so on, but I think the root value that they’re paying for is novelty. People will pay for access to new fiction (that they’re confident that they’ll enjoy) and there are revenue streams built around the fact that people will perceive access to new fiction (that they expect to enjoy) as being of value. (Advertising being the most obvious.)

Putting a story up on the web can only hurt its novelty value. It may be worth doing for other reasons (in particular, if you’re getting paid for it), but a piece of fiction is only new to a reader once.

Writers are as happy as anyone else to get paid, but they’re also motivated by other things. In particular, they want their work to be read: They want to be part of the great conversation that is literature—or at least part of some tiny piece of that conversation. This, I think, is the reason that so many writers are tempted to post their fiction: it means that the whole world has access.

Access

It might seem like putting your fiction up on the web would maximum the chance that it would be read, but that’s very much not true.

Fiction is different from nonfiction, where a brief glance can give the reader an pretty good sense as to whether or not a piece is worth reading. Fiction needs to be read from the beginning. Good fiction often produces temporary feelings of frustration or confusion and then resolves those feelings in a satisfying way. But there’s plenty of bad fiction that produces frustration or confusion and then fails utterly to produce a satisfying resolution.

Every reader has been repeatedly unsatisfied by bad fiction. Most of them have responded by choosing not to read random pieces of fiction. Instead, they only read fiction by writers that they trust to make it worth their while, or after someone they trust vouches for it as being worth the effort.

These pieces—fiction by writers they trust, or selected by editors they trust—they’re willing to pay money for. But fiction that lacks such credentials is not only not worth money, it generally doesn’t even get read. Just offering it for free does not make it worth investing the time to read it—in fact, just the opposite. Being available on the web for free doesn’t prove that it’s not worth reading, but in the absence of a recognized by-line or an endorsement by an editor, being offered for free is a negative.

Because of that, posting a story on the internet usually means that almost no one will read it except the writer’s friends and relations. In this way it’s very different from software, and from other things that have flourished on the internet, such as music.

[In the interest of full disclosure, let me mention that my story “An Education of Scars” is currently available to read for free on the internet at Futurismic, which paid me for the right to offer it.]