Whether I’m trying to “get enough exercise” (as I tried to do for years), or trying to “fill my days with movement” (which I’ve realized is a much better way to think about my physical activity), training has been a constant. As someone who has only rarely trained as part of a group, or had a teacher or coach, a lot of my training has been solo training.

Often my focus was on endurance training: preparing for very long walks, foot races, or a 100-mile bike ride. I also did strength training. And my training often included skill training—Tai Chi, parkour, tennis (long ago), even fencing (one brief term in college).

Training by yourself is hard. It’s hard to motivate yourself to go out and do it, and it’s hard to push yourself enough to make good progress (and if you’re good at pushing yourself, it’s hard to know when to take time to recover instead). For skills-based training, it’s hard to learn those skills without a teacher or coach. And for activities with any sort of competitive element, such as tennis or fencing, it’s especially hard to train without a partner. This has been particularly acute during the pandemic, but really it’s always true.

And here is where Guy Windor’s new book The Windsor Method: The Principles of Solo Training comes in.

A lot of the specific information in the book is stuff I’ve figured out myself over the years: Some training is just about impossible to do without a teacher (learning your first Tai Chi form) or a partner (practicing return of serve in tennis). But for most activities, that fraction of the training will be much less than half of your training. Much of the rest of your training is either easy to do by yourself (strength and endurance training), or at least possible to do by yourself once you’ve learned the skill well enough to be able to evaluate your own performance (practicing a Tai Chi form, for example).

The key is to spend some time figuring out the entire scope of your training activities, and then think deeply about what category each activity falls into.

To the extent that your access to a teacher, coach, or partner is limited (as during a pandemic), emphasize the things that are easy to train solo (such as strength training and endurance training), then judiciously add those parts of the training that are advantaged by (or require) a teacher or partner as they are available.

What Guy Windsor adds to this sort of intuitive structuring of training is, as the title suggests, a method. He has systematized the structure in a way that makes the decision-making parts of the activity easier to do and easier to get right.

Perhaps even more important than that, he has taken a step back to talk about all the parts of training that aren’t just skills training for your particular activity. That other stuff—sleep, healthy eating, breathing, mobility, flexibility, strength training, endurance training, etc.—are actually more important than this or that skill, while at the same time being the bits that are easiest to train solo. If you’re stuck for a year with no partner, no teacher, and no coach, but you spend that year focusing on health and general physical preparedness, you’ll scarcely fall behind at all, and make yourself ready to jump into your skills training with both feet once that’s possible again.

I should mention that Guy Windsor’s book was written with practitioners of historical European martial arts especially in mind, but that scarcely matters. It is entirely applicable not only to practitioners of any other martial art, it is entirely relevant to literally anyone who trains in anything.

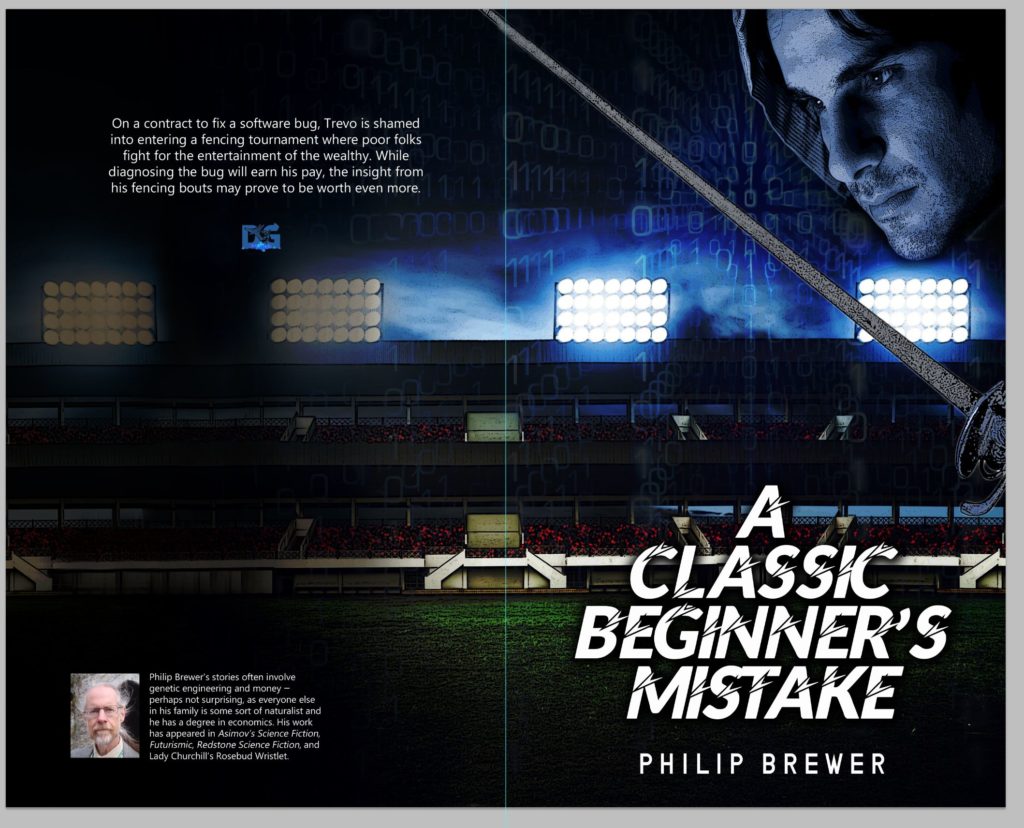

And, since many of my readers are fiction writers, I should also mention another of Guy Windsor’s books Swordfighting for Writers, Game Designers, and Martial Artists. When I signed up for his email list, he offered it as a free download for people who did so.

Being forced into purely solo training for 18 months has made me keenly aware of the many opportunities for non-solo training available here locally. There’s a local fencing club that I’ve had my eye on for some time, and our financial situation is such that now we could afford for me to join and buy fencing gear. Just today I searched for and found a local historical European martial arts club on campus—I’ve asked to be added to their Facebook group and joined their Discord. One of my Tai Chi students teaches an Aikido class with the Urbana Park District—I had started studying with him right as the pandemic began and got in two classes before everything was canceled. And, not sword-related, but cool and great training, is indoor rock climbing at Urbana Boulders.

Just as soon as the pandemic lets up for real, I’ll be doing some of those things.

In the meantime, I’m going over my solo training regimen, taking advantage of the insights that Guy Windsor provides in The Windsor Method: The Principles of Solo Training to figure out what adjustments I should make.