Today was a rest day, but yesterday I did three rounds on my rings:

- Jump rope

- Dips (best set x 2 + 5 negatives)

- Walking lunges

- Inverted rows

- 3-way core (30″ each hollowbody, inverted plank, shoulder taps)

Today was a rest day, but yesterday I did three rounds on my rings:

Back in 2020 I bought a set of gymnastic rings, and used them for pull ups, dips, and inverted rows during the period that fitness rooms were closed due to the pandemic. More recently, I’ve been doing a lot of club and kettlebell swinging—using equipment that was unavailable during the pandemic, but that I’ve purchased since.

I like the club and kettlebell stuff. However, probably because I’m not programming the workouts as well as I might, I don’t seem to be making progress. In fact, in some ways I’m backsliding. So, now that the weather supports getting outdoors and putting my rings up again, I’m going to do more of those workouts.

Today I did a circuit with three rounds of:

This picture has nothing to do with my workout. I took it while walking the dog at dawn.

Today’s workout was hill sprints at Colbert Park. Did a few warmup sprints at 40% up to 80%, then 4 working sprints at 90–95%.

Me and Ashley, out for a #run. Once again, she’s a much better running companion than she is portrait model. 🏃🐕 #dogsofmastodon

Because of dog-related complications, I didn’t get good stats on the run, but it was about 2 miles and maybe 30 minutes (including time to water the dog and pose for photos).

The books say not to take your dog running until they’re at least a year (better: 18 months) old, so they’re running on mature bones and joints.

Early on, I instead let Ashley take me on runs, letting her drag me on the leash while she sprinted off in random directions at breakneck speed for 30 or 40 seconds, only to cut in front of me and then come to an abrupt stop. It wasn’t really satisfactory. After I fell and badly split the skin on my knee, I mostly quit doing that. If I wanted to go for a run, I’d leave the dog behind with Jackie and run by myself. But that was unhandy for all of us.

Now that it’s spring, and we’re getting some nice running weather, I thought I’d see if Ashley could run with me.

I’d done some preparation: In the winter I took a “loose-leash” walking class, and she’d gotten a lot better at walking with me. For loose-leash walking I wrap the leash around her chest and then back through that loop you can see on the collar in the picture. That has a couple of positive effects: the leash is effectively shorter, and when she does pull, the friction from the leash constricting around her chest makes the pull gradual, rather than an abrupt hard yank. The key, though, is that it serves as a signal that I want her to walk like a pet, and stay by my side, and she’s gotten pretty good at doing so.

Yesterday I thought we’d give running together a try, and it worked great! I walked her a few blocks on a long leash, so she could get her sniffies in. Then, once we reached a multi-use path that’s about a quarter mile away, I put her on the leash wrap, and started running—and she did just what I wanted her to! She ran along, next to me, at my pace. She didn’t try to run off in some other direction. She didn’t try to sprint ahead. She didn’t lag behind like she didn’t want to run. She just loped along next to me.

It was great!

I had neglected to bring water for her, so I was a little worried that she’d overheat, but she seemed to do okay. We ran a mile, then turned around and walked partway home, but when it seemed that she wasn’t overheated, I picked up the pace again and we ran the rest of the way back to our starting point, then I put her back on a loose leash and we walked home (where she did proceed to drink a whole bowl of water).

For future runs I will bring water. I’ll also make a point of getting out early, before the weather gets hot.

If this doesn’t turn out to be a one-off thing, and she’s willing to run with me on a routine basis, I’ll start taking her running every other day, sticking to short runs for a while to make sure we don’t over do it, then gradually increase the distance until one or the other of us hits some limit or another. (I’ve been routinely walking her over 6 miles nearly every day, so we’re both already in pretty good shape.)

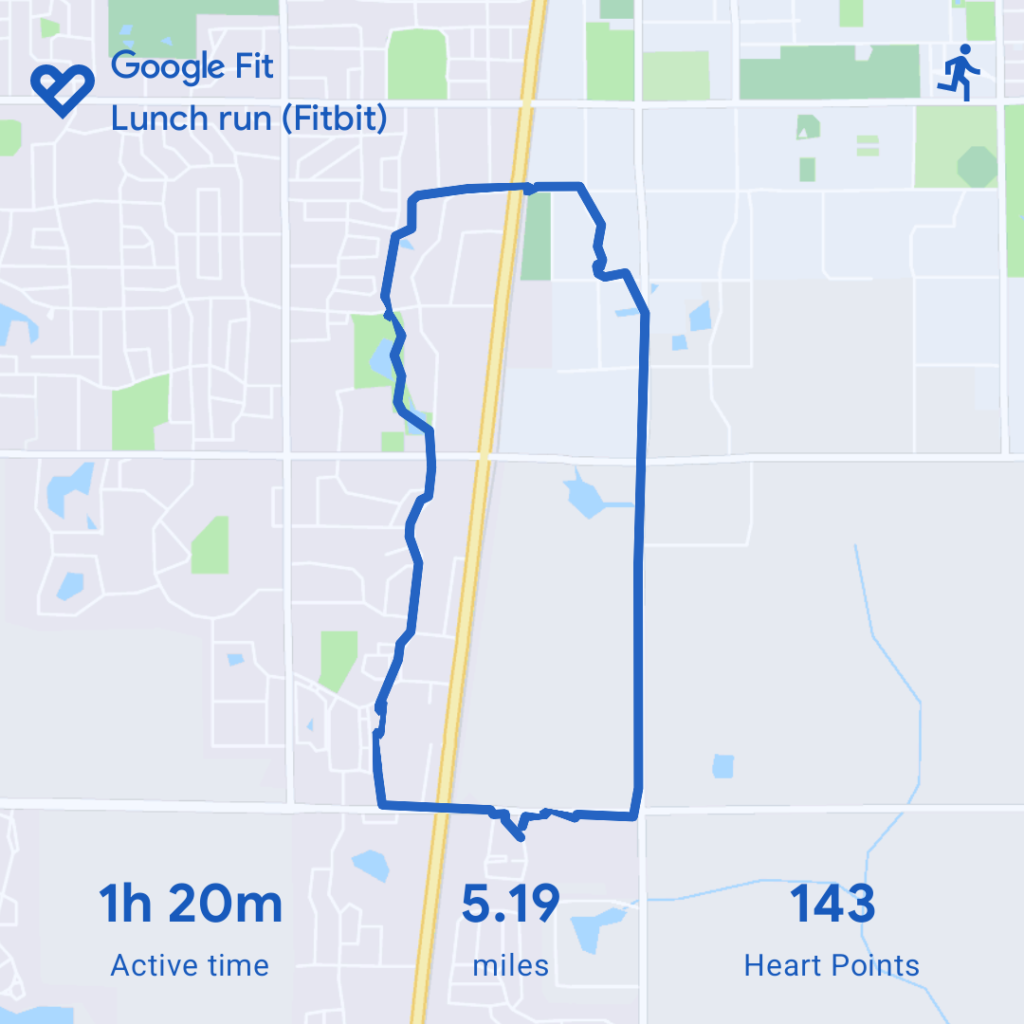

A great #run! 🏃 My feet and knees felt great throughout. And it looks like the weather will finally support getting out twice a week. (This was my “long” run. I also want to do a “fast” run.)

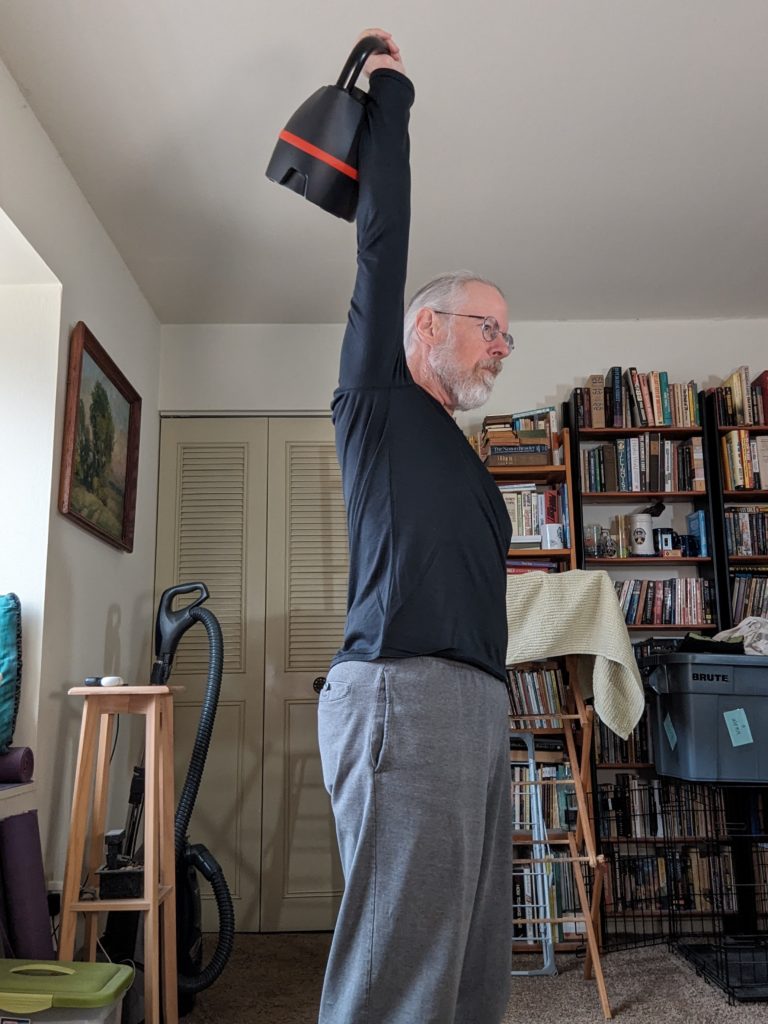

A couple of aspects of longsword turn out to be hard not from a skill perspective, but from a simple strength and endurance perspective. Look at the guys in this picture. Their arms are fully extended, either forward or upward. That’s just hard to do for minutes at a time. Besides that, they’re in a pretty low lunge position. That’s also hard to do for minutes at a time.

A couple of days ago, I had a chance to ask celebrity trainer Mark Wildman how he’d program for building arm strength and endurance. It turns out he’s a huge longsword geek. Here’s the video, cued up to where he reads my question (should be 41:57). The related stuff goes through 48:50).

My original question was: “I’m doing longsword. One issue is arm strength and endurance. I’m doing kettlebell clean&press and pushups (for holding the sword overhead and extended forward). Any other ideas?”

Here are my notes on Mark’s reply:

Mace & Club

Single-arm heavy club program (a program that isn’t for sale yet, but that is pretty easy to deduce from the videos on Mark Wildman’s youtube channel).

Basis of Strength (2-Handed club program that does exist, although it’s pretty expensive).

Mace 360s. (The mace equivalent of a club shield cast: You bring your hand past your opposite ear, swing the mace behind you, and catch it back in front.)

Cut the Meyer square for time. (I don’t think he said WHAT time would be appropriate. Maybe do a 10-minute emom, where you do the full square, rest until the end of the minute, and then repeat. Or maybe 30 seconds on/30 seconds off.)

He emphasized training both dominant hand and non-dominant hand.

This, by the way, goes against the advice of Liechtenauer, who says:

Fence not from left when you are right. If with your left is how you fight, You'll fence much weaker from the right.

I suspect that the difference has to do with your goals. Liechtenauer was speaking to someone who had to win sword fights. Wildman is speaking to someone trying to get fit for a hobby.

Push ups as part of a warm-up. (Since I had mentioned pushups.)

Instead of pushups, do burpies in full HEMA gear. (Oy.)

Don’t do actual sword movements with mace or club. Do those with an actual longsword.

Mace drop swing in Meyer stance (4 versions: contra- and ipso- lateral with each foot forward): Here’s two videos of that:

I’ve ordered a mace so I can try that (and other mace stuff). I haven’t yet pulled the trigger on the (expensive) Basis of Strength program, although I’m tempted. While I ponder that, I’ll start doing mace drop swings while in a lunge, and see if I can get both my extended arm strength and endurance up, while also improving my Meyer fencing stance.

I’ve been training in longsword for almost a full year now—I just looked and saw that my first two classes were in the last week of March last year—and I’d gotten kind of discouraged. I did okay the first few weeks, but then plateaued. For months I felt like I was making no progress at all. Finally, on Thursday, I felt like I had taken a step forward.

I’ve come up with training-at-home plans a couple of times in the past year, thinking that I need to work out my Meyer stance (very low lunge, with the front thigh almost parallel to the ground), and of course my cuts. (This pictures shows me doing a zwerchhau, and the cut looks pretty okay, although the stance isn’t nearly low enough.) That is, I’d come up with the plans, but I largely hadn’t followed through. Today, with the encouragement of having done okay on Thursday, I got out with my sword and spent a while working on low stance, Meyer square cuts, and zwerchhaus.

Several members have done a “bear pit” for their birthdays: The birthday boy faces everyone in the group for a pass or three, one after another. The exact details vary, but the idea is to pick some metric (passes or opponents) and do enough to hit your age. I’ll turn 65 in mid-June, and I’d like to be able to carry on the tradition. I think I’m within striking distance on the basic fitness. (I was doing 2-hour runs at the end of last summer, and my last run was 1 hour 14 minute.) But it wouldn’t be much fun to face opponent after opponent and get beat every time, so I’m pleased to finally feel like I’m making some progress.

If you’re local, and you think swords are cool (and who doesn’t?), you might check out our group: Tempered Mettle Historical Fencing.

My lowest resting heart rate has crept up these past few months. My Oura ring keeps saying that I need to take it easy, but I think I need to do a few more long runs. So I’m going to test that theory.