My lowest resting heart rate has crept up these past few months. My Oura ring keeps saying that I need to take it easy, but I think I need to do a few more long runs. So I’m going to test that theory.

My lowest resting heart rate has crept up these past few months. My Oura ring keeps saying that I need to take it easy, but I think I need to do a few more long runs. So I’m going to test that theory.

Based on the ideas that I talked about in Training for everything, here’s my latest cut at a personal exercise program. (My first cut was derailed by circumstances, and then I adopted a dog which derailed everything except dog walking. Then I got West Nile fever.) See my no-longer-particularly-recent Starting to rough up a new training plan for more information about the specific exercises and how I organize them into sets, reps, and progressions.

I have a set of exercises that I want to do, ideally twice a week each:

That’s five things, so if I did each twice, and gave everything its own day, I’d have to have a 10-day week. That isn’t impossible. In fact, I’ve seriously considered planning my workouts in a longer cycle than weekly in the past, it but is unhandy in various ways. Fortunately, I think I can double-up several of these exercises in a way that will let me fit them into 7-day week.

The 1-handed club swinging isn’t particularly intense cardiovascularly, so I’m thinking I can combine it with the clean & press. The KB swings is intense cardiovascularly, but because it’s very different, I’m thinking I can combine it with the gymnastic rings bodyweight circuit, doing the KB swings as a “finisher” after the rings workout.

My HEMA (sword fighting) practice is three times a week, and I can’t adjust that schedule, except by skipping workouts, so I have to work that in when it actually happens.

Of course I also want to get one day a week of complete rest. I’d normally make that Sunday, but there’s a HEMA practice session on Sunday so it’ll have to be on Saturday instead.

So here’s a quick stab at a possible weekly plan:

| Day | Morning | Midday | Evening |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sunday | Rings circuit / KB Swings | HEMA | |

| Monday | 1-H Heavy Club / KB C&P | ||

| Tuesday | Sprints | HEMA | |

| Wednesday | Rings circuit / KB Swings | ||

| Thursday | 1-H Heavy Club / KB C&P | HEMA | |

| Friday | Long run | ||

| Saturday | Rest |

I’ve omitted a “warm-up” block, because I already do my morning exercises, my ridiculously long warm-up routine, nearly every day. I’ve also omitted my dog walking, which averages something over 6 miles a day.

I’m pretty happy with this. It has my HEMA practice sessions in at the correct times; it leaves open the time slots where I have Esperanto, and meeting friends for lunch; it has a full rest day.

I don’t show it here, but I’ll definitely do a de-load week every 5 or 6 weeks.

I should be very clear that, at this point, this is entirely aspirational. I’ve been doing each of these workouts individually, but the only combined workouts I’ve tried so far are the heavy club swinging and the clean&press workouts. I’ve also been taking more than one rest day per week. But the progress I want seems to depend on doing something like this workout schedule, so I’m going to give it a try.

I’ll report back regarding my success or failure.

I’m only rarely in shape to run 7+ miles, and even more rarely in shape to do it in the winter. 🏃🏻♂️

I spotted this toy in mile 4, and paused to get a photo.

Some fitness guru that I follow on the internet—I think it was Andrew Huberman, although it might have been Andy Galpin—suggested that the optimal ratio of resistance and endurance training was 3-to-2—but also suggested that which one is emphasized should switch after some number of months.

So, you might combine three strength-training workouts per week with two endurance workouts per week for some number of months, and then reverse the ratio and go with three endurance workouts per week combined with two strength-training workouts per week.

This is interesting to me mainly because I seem to intuitively be doing exactly that. All through 2020 I was emphasizing resistance exercise (often 4 workouts per week), and limited myself to a single run most weeks. (Due in particular to a sore foot, but also just because it felt right.) I generally included an HIIT session most weeks—so also endurance training, even if not long steady-state training.

Early in 2021 I had made a plan to repeat Anthony Arvanitakis’s Superhero Bodyweight Workout, which I’d used the year before to good effect. I even bought the latest version, which seemed slightly better. But then a minor medical issue meant I had to defer the super-intense workouts that it called for. Once the medical issue was resolved I figured I’d get back to it, but as the year progressed I started feeling like running more and longer. My foot was no longer troubling me, and I always enjoy long runs.

I found myself doing less lifting and more running. Just lately it occurred to me that what I wanted to do was three runs per week, and maybe just two lifting sessions—which would be nicely in accordance with the suggested adjustment in workout ratios.

So that’s my plan for the rest of the winter—three runs per week, with just two lifting session. Then maybe in the spring I’ll switch back and reemphasize lifting.

For years I had trouble running into the winter. I eventually figured out that I’d simply had the wrong idea about how to do it. I’d imagined that if I just continued running through the fall, I’d gradually ease myself into winter running. That never worked—because there are plenty of warm days (or at least warm hours) through early fall, and then in middle or late fall there is (identifiable only in retrospect) a last warm day, and then it’s cold nearly every day until late March or early April. So even if I ran through fall, if I chose to get in my runs during the warm hours, I wouldn’t actually develop tolerance for the cold, the wardrobe for handling it, or the skill at picking the right garments.

A couple of years ago I failed to run through the fall, and then decided to develop a winter running habit anyway. I bought a few pieces of cold-weather gear—plenty, because I was generally only running once or twice a week.

I started with the sweats I wear to teach taiji, and then I added two pairs of tights—one sort of classic running tights, and then another pair of fleece tights, that ought to be good down to colder than I’m every likely to try to run in.

For tops I generally wore a regular sweatshirt over a regular cotton t-shirt. Then I got some short- and long- sleeved merino t-shirts, which are vastly better as a base layer. I also dug out a capilene half-zip top that my dad gave me a few years ago, which was just the thing when it got a little colder.

I also got a washable merino knit hat in high-viz yellow, and two different pairs of gloves in high-viz yellow—first a pair from the dollar store, which were not nearly warm enough, then a pair from Amazon that I think was marketed to people directing traffic, that were dramatically more high-viz, but still not quite warm enough.

Now that I’m in my third year of winter running—and now that I’m running more times per week—I’ve added a few more pieces of winter running garb.

I bought a third pair of high-viz gloves, these from Illinois Glove company, which are finally warm enough, and almost as high-viz as the previous pair.

Last winter I picked up a pair of Janji Mercury Track Pants, which are wonderful. Size medium fits me perfectly, they’re warm enough down to well below freezing (and I rarely run when it’s below freezing, because of slipping hazards). I liked them so much I picked up a second pair last year, and just now got a third pair (because a couple of weeks ago I wanted to go for a run and both of the first two were already in the laundry).

Last year I added another quarter-zip pullover in some high-tech fabric that I picked up cheap at Amazon, and just now today another fancy Patagonia capilene base-layer top that I can wear either by itself, over one of my merino T-shirts, or under a wind-proof or water-proof layer.

I’ve gone running five or six times in the last couple of weeks, at temperatures ranging from right at freezing up to maybe 50℉, and so far I’ve managed to nail it each time as far as matching the warmth of the clothing to the conditions outside.

I have one more piece of running gear that I’ve ordered, but that hasn’t arrived: a headlight. Normally I just don’t run when it’s dark. (Since I don’t work a regular job, I have the freedom to choose to run only during daylight.) But a couple of times in the last few weeks, I wanted to go for a run that would start in the daylight, but might not finish until after dark. I figured that a headlight might be very useful as a just-in-case piece of safety equipment, even if I didn’t plan on doing much nighttime running. I ordered this Spriak Wide-Beam headlight, which seems like it would serve my purpose as emergency safety gear. If I end up running in the dark on purpose, rather than by accident, I’ll be tempted to step up to this Petzl Headlamp that offers 3x to 15x the battery life, and what looks like a rather better system for fitting the whole thing on your head, but costs 10 times as much ($200 vs. $20).

(FYI: Those Amazon links are affiliate links. The non-Amazon links are not.)

If circumstances develop in any sort of interesting direction—if it turns out that the gear I’ve got doesn’t cut it for this or that sort of conditions, or if I decide that I need some other bit of fancy running kit, or if one of the things I’ve got turns out to be even more suitable than I’ve already described, I’ll go ahead to write another post.

If you’ve got great winter running gear, I’d be very interested to hear about it! Comment below or reach out on social media or by email (see my contact page for ways to connect to me).

Bought two of these peach-colored shirts for summer running. They’re a little loose on me, so not especially flattering, but the fabric is wonderfully soft and comfy. I kinda wish I’d bought three.

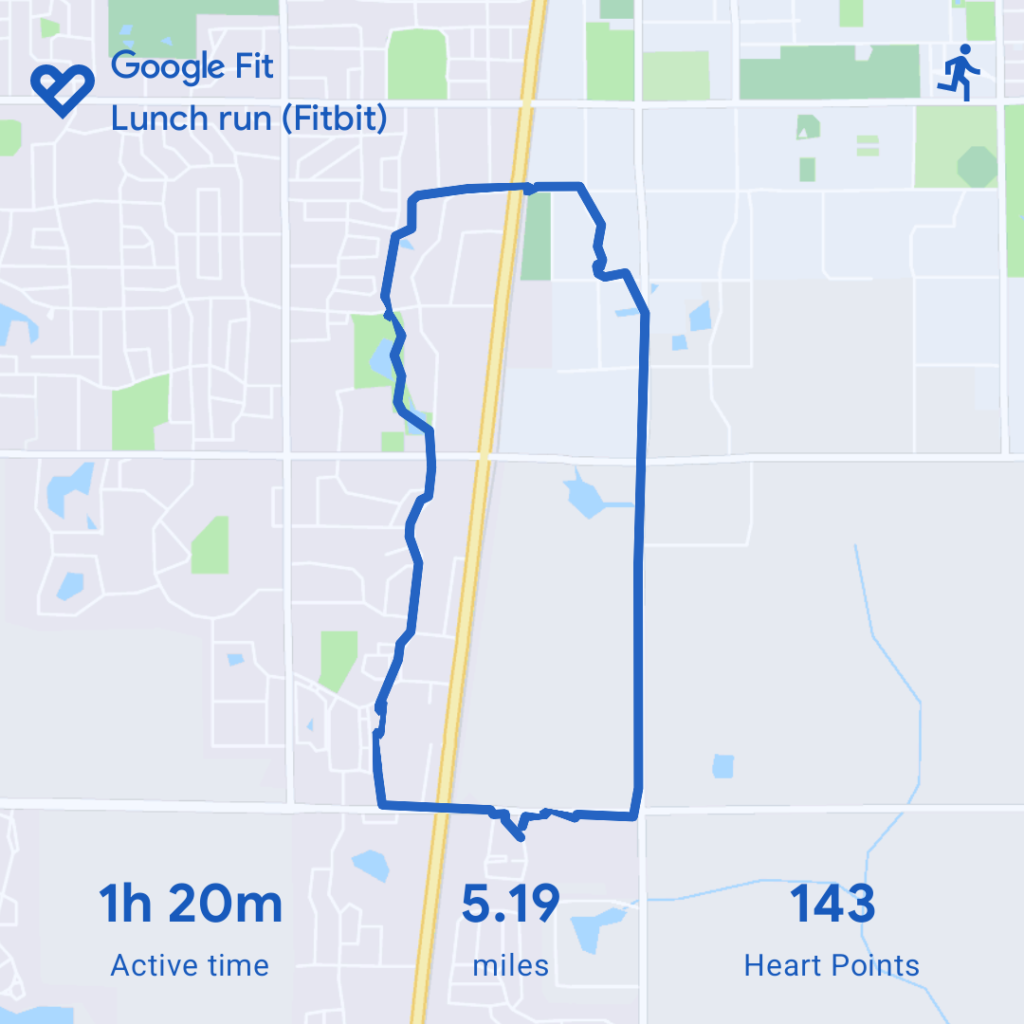

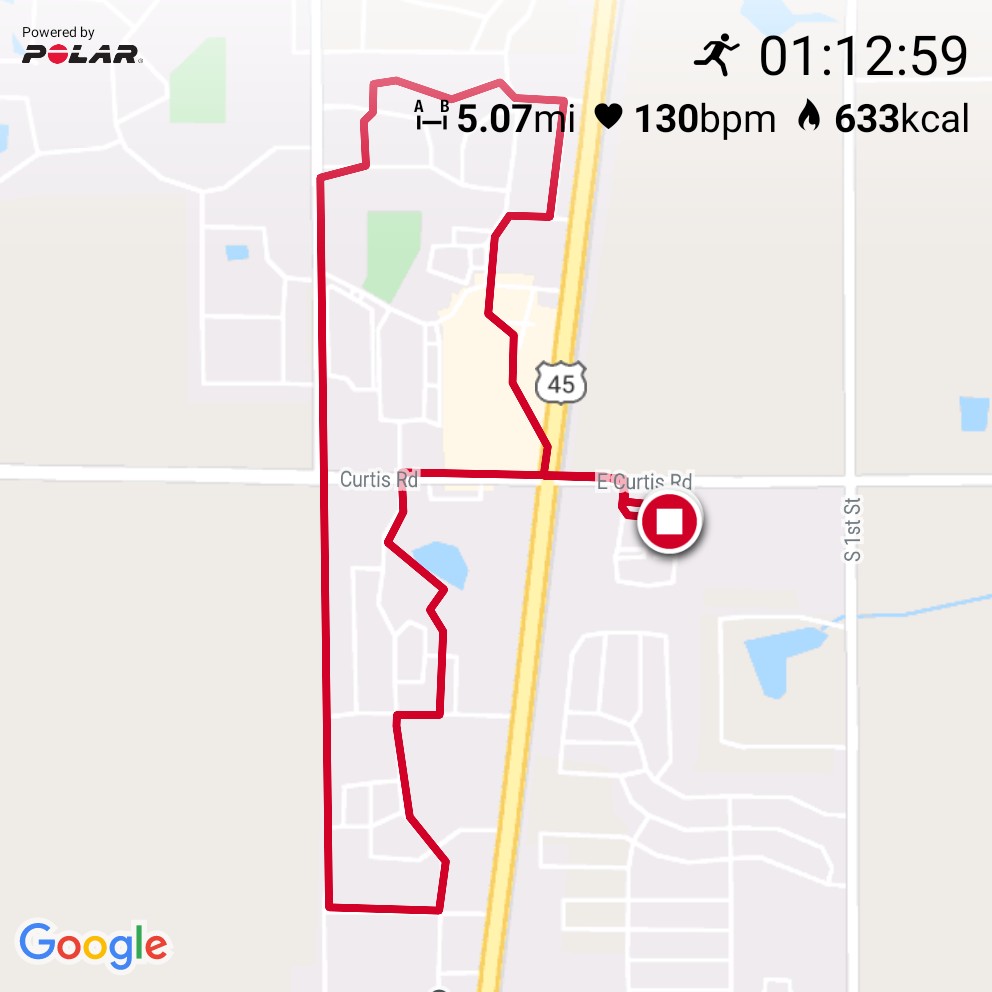

At just over 5 miles, this was my longest run in a very long time. (I just checked: I ran a fraction of a mile farther back in April of last year.) Cold, but I have the clothes for it. 🏃🏻♂️

This year was obviously strange in all sorts of ways, so I figure it’s not so strange that my movement practice got strange.

One thing that seems very strange to me is that I reverted to doing a lot of exercise, after having made a big deal the past few years of scorning exercise in favor of movement. I wrote a whole post on this recently (Exercise, movement, training), so I won’t repeat all that stuff here, except to say that the pandemic response provided me with a lot of opportunities to exercise, while restricting my opportunities to move and to train.

Around the beginning of the year I had a realization that what had held me back from achieving my fitness goals was not (as I had been supposing) a lack of intensity, but rather a lack of consistency. I responded by getting very serious of getting my workouts in, and was pretty pleased about having established a proper workout habit when just a few weeks later the pandemic led to our local fitness room being closed. I found this momentarily daunting.

As I’ve mentioned elsewhere, it was around this time I saw this hilarious tweet:

To which my response was “Challenge accepted!”

The biggest problem with losing access to the fitness room was losing access to the pull-up bar. I looked around for alternatives, found that gymnastic rings were available and affordable, and I ordered a pair.

Easily the best purchase I made last year.

The addition of gymnastic rings made for a big change in my exercise regimen. I use them for three exercises: pull ups, inverted rows, and dips. I had worked pretty hard on pull ups before, but upon getting the rings I redoubled my efforts. As far as inverted rows and dips, I had played around with both, but now I got serious.

I round out my upper-body exercises with push ups.

For lower-body exercises I experimented with a variety of possibilities: squats of various types, kettlebell swings, burpees, lunges, etc.

One milestone was achieving my first pull-up. Another was the first time I did two pull-ups. Later I manged (a couple of times) to do three pull-ups!

I just wrote about how kettlebell swings taught me something about the value of doing lots of reps. Based on that, for my indoor workouts (where it’s not handy to set up my rings), I’ve started doing more exercises for high reps. Not enough data yet to know how that’s going to work, but it seems like a valuable experiment.

For a long time—at least many months, maybe more than a year—I’d had a sore foot that got worse when I ran. I repeatedly cut back or eliminated runs, had my foot get better, and then had it start hurting again as soon as I started running again. This past summer I finally took a full month off from running, which seems to have been what my foot needed.

I’ve very gradually resumed running. For some weeks I kept my runs down around just one a week and just 2–2.5 miles. Then up to a 3–3.5 miles. I did one 4 mile run, which didn’t seem to cause any problems, but then I did a run of nearly 5 miles, which did make my foot sore the next day. I took a break until the pain was completely gone and eased back to 3–3.5 miles, and all seems well.

I’ve just started doing two runs per week, a “long” run (slightly over 3 miles) and a “fast” run (where I hold the distance down under 3 miles, but include a few 10-second sprints around the mid-point of the run). That felt really good the last time I did it. (My running gait seems to improve when I run fast.)

I’ve talked at some length about my adventures in getting a kettlebell during a pandemic, and about my experience with kettlebell swings producing unexpected hypertrophy, so I won’t repeat that here. I’ll just say that cold weather—and especially ice on the patio—have kept me from doing much kettlebell swinging in the second half of December. But literally every day I look out on the patio to see if it is clear of ice, and get out and do some swinging when it seems safe.

I added a jump rope to my exercise equipment a while ago, and back in March and April did enough rope skipping to recover the ability to do it. (That is, I could jump rope for 30 or 40 seconds with zero or one misses.) The problem was that jumping rope hurt my sore foot just like running did. I prefer running, so when I had to set limits on those exercises to protect my feet, I ended up mostly running, as long as the weather was nice.

As the weather turned chilly in the fall, and especially when we started having days when there was an occasional short period adequate weather, but not the sort of reliable block of nice weather that makes me think I can fit in a good long run, I started thinking that an occasional bout of jumping rope might be a great way to squeeze in a quick, intense workout during even quite a brief period of nice weather on an otherwise nasty day.

To make full use of such periods, I paid up for a weighted jump rope. I have to say I’m pretty happy with it. It’s very much the opposite of my old jump rope, which was just a plastic-coated wire—very light and very fast—marketed to martial artists and cross-fit types. Pretty good for getting lighter on your feet, and adequate for a lower-body workout, but not much for the upper body. The weighted jump rope (even the lightest one, at just ¼ lb) definitely turns the jump rope exercise into an upper-body exercise as well.

I haven’t had the weighted jump rope long enough to form a definite opinion about it, but after just a couple of sessions, I’m pretty pleased, and if the weather cooperates, I’m hoping to get multiple HIIT jump rope workouts in over the course of the winter.

My main non-exercise movement is and always has been walking, but I’ve done very little this past year. This was half due to the pandemic, and half due to Jackie having a sore hip that makes it hard for her to walk fast or for long distances. (I’ve been taking Jackie to physical therapy, and she’s getting better. We’ve been doing walks in the woods south of the Arboretum, and that’s going very well.)

With fewer and shorter walks with Jackie, and with walking for transportation almost eliminated by the pandemic, my non-exercise walking has dwindled pretty severely.

Ditto for my non-exercise running.

I have very much had my eye on parkour as the thing I want to get back to this summer. Since I have made great progress on strength training specifically with an eye toward parkour, I’m very hopeful.

I’ve been doing just a bit of training, even without being able to get together with other traceurs.

The most active member of the campus parkour group turns out to have moved to Colorado. I’ve been in touch with him, and he seems to mean to spend at least some time here this summer, so hopefully I can put together some sort of training with him. In the meantime, I ordered one of his t-shirts, so I’ll have something to wear.

Like everything else, the taiji classes I used to teach at the Savoy Rec Center had to be abruptly canceled back in March.

During the spring I led a few group practice sessions via Zoom. They’re better than nothing, and at least keep the group connected.

Once the lock-down restrictions in Illinois eased up a bit in April, my group started meeting in the park, and we continued to meet through the summer. Once the weather turned, I resumed the on-line practice sessions.

Unlike a lot of my students, who don’t feel like they can do the taiji practice without someone to lead them, I can actually do a full practice session entirely on my own. And I occasionally do. But without the group being there, it’s hard to get motivated.

Still, I almost always include some qigong as part of my morning exercises, do the once-a-week group practice session, and occasionally do the full 48-movement form (if only to make sure I don’t forget how to do it).

Looking ahead, of course, is all about the end to the pandemic, something that I have high hopes for. If I can get vaccinated by June, let’s say, then by July maybe I can resume normal activity (while wearing a mask and maintaining social distance, of course, but actually interacting with people other than just Jackie).

Normal would include hiking in the woods, and maybe visiting some natural areas within a few hours drive. (We’ve pretty much completely avoided going anywhere so far that we couldn’t go, hike, and return without having to use a restroom.)

Normal would include practicing parkour with the campus group.

Normal would include resuming teaching taiji in the fall.

I had scheduled a visit to Urbana Boulders to do some wall climbing right when the lockdown started, so that fell by the wayside. I had actually started taking an aikido class when we had to stop because of the pandemic. Either one of those things might happen, once the pandemic ends.

Basically, I have high hopes for 2021.

Objectively speaking, autumn is probably the best season. Not cold like winter, stormy like spring, or hot like summer, autumn has great weather—totally aside from the pretty colors and Halloween (arguably the best holiday, albeit in a near tie with Groundhog’s Day).

For pretty much my entire adult life I’ve dreaded the cold dark days of winter, and among the many ways that Seasonal Affect Disorder affected my life in a negative way was that it ruined autumn. I could usually get past the summer solstice okay (although in the back of my head, I knew that the best day of the year had come and gone), and I could keep it together through July and August. But by the beginning of September I knew that winter was coming, and I’d spend the last months of nice weather steeling myself against the dark days to come.

It was the dark that bothered me, more than the cold. It’s easy to armor yourself against the cold—flannel, moleskin, fleece, wool, down—there are many ways to deal with cold. But even a Verilux light therapy lamp (which does help) does not solve the problem of the dark days of winter.

All of which is merely an introduction to saying: Last winter I did not suffer from SAD!

I had meant to write something at the time, but I didn’t want to speak too soon, and then once it was spring, it didn’t seem like the most important thing.

I don’t want to jinx anything, and I’m sure the right combination of stressors on top of the cold and dark could once again put me in a bad place, but something more important has changed than just a good year: I’m no longer afraid of the dark days. Maybe I’ll suffer from SAD again, and maybe I won’t, but at least the mere knowledge that the cold and dark is coming is not ruining my fall! In the back of my head I seem to have turned a corner and developed some confidence that I’ll be okay despite the season.

So what has helped?

First, not having to work a regular job. I’m sorry that I can’t recommend something more generally available, but that was the biggest thing that made a difference. Because I don’t have to be productive on a day-to-day basis, I avoid the depression-spiral that used to result from realizing that I wasn’t getting anything done, which made me anxious about losing my job and being unable to support my family, having the anxiety make me more depressed, and the depression making me even less productive. That used to be a killer. On top of that, because I don’t have to be in the office during any particular hours, I’m able to spend a few of the few non-dark hours of the day outdoors, taking advantage of what daylight there is (and making some outdoorphins).

Second, exercise. I always knew it was important, but I took things up a notch each of the last few years, and each new tick up turned out to provide an enormous improvement in my mood. In my experience, all kinds of exercise are good. Endurance exercise is good. High-intensity interval training (HIIT) is good. Skill-based training—ballet, parkour, animal moves, taiji—is good. Resistance exercise (lifting) is perhaps best of all. Letting the dark days of winter compress you down into a lump that seeks (but never finds) cozy because you’re unable to move? That’s the worst.

Third, community. Granted this is not so easy during a pandemic, but even people that you only see on-line are still people you can have a connection with, and having connections is good.

Fourth, something to look forward to. It can be almost anything. Last year I was looking forward to having my family visit. Other years I’ve looked forward to taking a vacation somewhere warm. Even little things help me—ordering some fountain pen ink or cold-weather workout clothes and then looking forward to the package being delivered, and then looking forward to using the newly acquired item.

Fifth, a project that you can make progress on. Ideally something without a deadline—at least, no deadline during the dark days of winter—but a project that you care about. Something that you can spend a few minutes on every day and see some headway that brings you closer to completing it. Creative projects are good, but creativity isn’t as important as just having a thing that you’re working on, and making steady headway.

Not suffering from SAD, even if just for one year, has been wonderful. Having some confidence that things will be okay-enough this winter that I’m not spending all fall dreading it is even more wonderful-er.

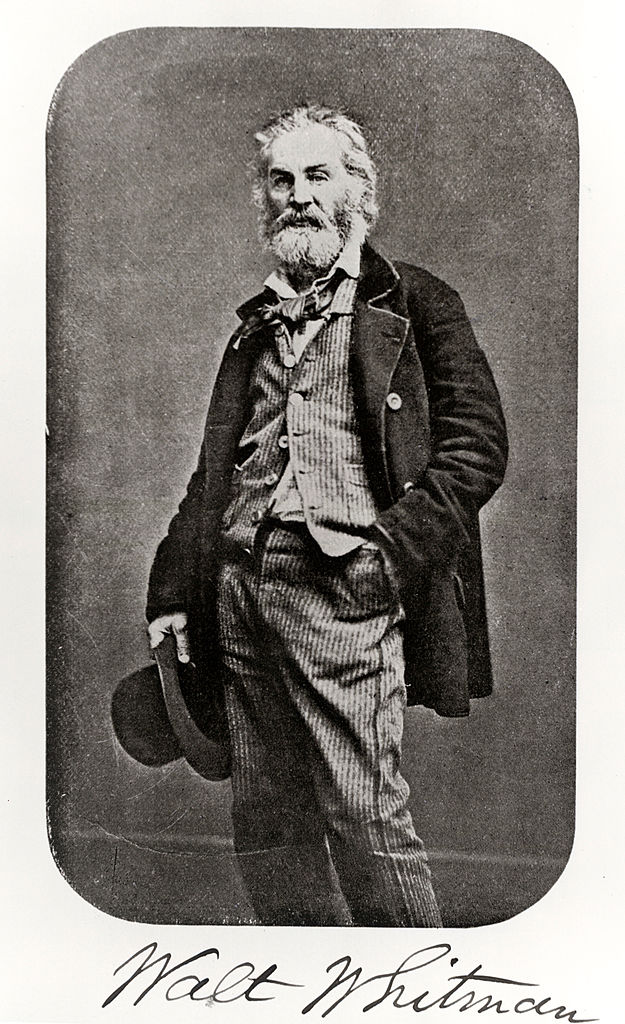

I actually knew this already, having seen an article about the work, originally serialized in the weekly journal the New York Atlas under the pseudonym Mose Velsor, when it was collected and republished as a PDF (Manly Health and Training) in 2016. But I hadn’t read through the whole thing until this month.

I’ve read a lot of fitness books over the years, and one thing I find interesting is how much they are all the same—including Walt Whitman’s. Of course, every fitness book has its own peculiarities—more or less focus on functional fitness, flexibility, muscle size, body fat, strength, quickness, power, control, aerobic capacity, aesthetics, etc. But the levers available to affect these things don’t really change: sleep, diet, resistance exercise, endurance training, and stretching just about cover the gamut. Aside from the details of the diet, it’s primarily a matter of selection, focus, and combining of exercises.

Walt Whitman’s fitness manual offers a nice little selection of exercises, none of which would seem out-of-place in any modern fitness book:

Walt Whitman wants his readers to be exemplars of manly beauty. In fact, based on how he talks about it, you have to assume that increasing the amount of manly beauty around is really the most important thing he hopes to achieve with his book—but that’s a fair thing to do, because:

As regards human beings, in an important sense, Beauty is simply health and a sound physique. We can hardly conceive of a man, at any age of life, who is in perfect health, and keeps his person clean and neatly attired, who has not some claims to this much-prized attribute.

Related to this, he is clearly keen to normalize men caring about aesthetics:

Nor is there anything to be ashamed of in the ambition of a man to have a handsome physique, a fine body, clear complexion, nimble movements, and be full of manly vigor. Ashamed of! Why, we think it ought to be one of the first lessons taught to the boy, when he begins to be taught at all. It is of quite as much importance as any grammar, geography, or arithmetic— indeed, we should say it was of unrivalled importance.

Of course, some things are desirable for more than just their aesthetic benefits:

The beard is a great sanitary protection to the throat—for purposes of health it should always be worn, just as much as the hair of the head should be. Think what would be the result if the hair of the head should be carefully scraped off three or four times a week with the razor! Of course, the additional aches, neuralgias, colds, &c., would be immense. Well, it is just as bad with removing the natural protection of the neck; for nature indicates the necessity of that covering there, for full and sufficient reasons.

An aside, because it touches on both dancing and aesthetics: A few years ago I read a fitness book titled something like How to Have a Dancer’s Body, which I read hoping to get some suggestions for improving strength and flexibility, only to be sadly disappointed. Its advice in those areas, after a brief treatment of stretching and posture, was that the student should find a good dance class and workout under a teacher. (Most of the book seemed to be about normalizing having an eating disorder—which, admittedly, is probably essential if you want to have the body of a prima ballerina.)

Dance’s attractiveness comes, I think, from the way it both provides actual (often astonishing) physical capability along with an aesthetic that I and many other people find attractive. Walt agreed on both counts, although seemed to take issue with the dance fashions of the times:

As originally intended, dancing was meant to give harmonious movements to the whole body, from the legs, by keeping time to music. In that sense, it was a beautiful art, and one of the noblest of gymnastic exercises. Modern arrangements have made it something quite different.

We would be glad to see some manly genius arise among the dancing teachers, who, out of such hints as we have hastily written, would assist the objects of the trainer and gymnast.

As I said, all fitness books are pretty much the same, so I am not really surprised to find things here that read exactly like something I might find in some entirely modern source of fitness advice.

For example, his rant on shoes and feet sounds exactly like what you might expect if Walt Whitman wrote some copy for Katy Bowman’s Nutritious Movement shoe page or Steven Sashen’s Xero Shoes.

Probably, in civilized life, half the men have more or less deformed feet, from the tight and wretchedly made boots generally worn.

In one of the feet there are thirty-six bones, and the same number of joints, continually playing in locomotion, and needing always a free and loose action. Yet they are always squeezed into boots not modeled from them, nor allowing the play and ease they require. For the modern boot is formed on a dandified idea of beauty, as it is understood at Paris and London, and not as it is exemplified by nature.

If you want to see the feet in their natural and beautiful proportions, you must get a view of the casts of the remains of ancient sculpture, representing the human form, doubtless from the best specimens afforded by the public games and training exercises of the Greek and Roman arenas. They exhibit what the foot is when allowed to grow up, with its free, uncramped, undeformed action. There have been no artificial coverings or compressions; and we know that the gait therefrom must have been firm and elastic. We can understand how the Macedonian phalanx, or the Roman legion, performed its long day’s march. We can see the ten thousand Greeks pursuing their daily wearying course through the destroying climate of Asia, marching firmly, manfully, across the arid sand, the mountain pass, or the flinty plain. It is a truthful lesson we may learn, not for the soldier only, but for the civilian.

Probably there is no way to have good and easy boots or shoes, except to have lasts modeled exactly to the shape of the feet. This is well worth doing. Hundreds of times the cost of it are yearly spent in idle gratifications—while this, rightly looked upon, is indispensable to comfort and health.

Simlarly, his principle workout plan sounds exactly like a MovNat combo:

In truth, however, a man who is disposed to attend to the matter of strengthening and developing his muscular power, will be continually finding some means to further that object, and will do so in the simplest manner, as well as any. To toss a stone in the air from one hand and catch it in the other as you walk along, for half an hour or an hour at a stretch—to push and roll over, a similar length of time, some small rock with the foot, thus developing the strength of the knees and the ankles and muscles of the calf—to throw forward the arms, with vigorous motion, and then extend them or lift them upward—to pummel some imaginary foe, with stroke after stroke from the doubled fists, given with a will—to place the body in position occasionally, for a moment, with all the sinews of the arms and legs strained to their utmost tension—to take very long strides rapidly forward, and then, more slowly and carefully, backward—to clap the palms of the hands on the hips and simply jump straight up, two or three minutes at a time—to stand on a hill or shore and throw stones, sometimes horizontally, sometimes perpendicularly— to spring over a fence, and then back again, and then again and again—to climb trees in the woods, or gripe the low branches with your hands and swing backward and forward—to run, or rapidly walk, or skip or leap along—these, and dozens more of simple contrivances, are at hand for every one—all good, all conducive to manly health, dexterity, and development, and, for many, preferable to the organized gymnasium, because they are not restricted to place or time. Nor let the reader be afraid of these because they are simple, but form the daily habit of some of them, without making himself uneasy “how it will look” to outsiders, or what they will say.

The book especially addresses people who are in school, telling them to be “also a student of the body,” but wants to be sure that the reader knows that not only students are the intended audience:

To you, clerk, literary man, sedentary person, man of fortune, idler, the same advice. Up! The world (perhaps you now look upon it with pallid and disgusted eyes) is full of zest and beauty for you, if you approach it in the right spirit! Out in the morning! Give our advice a thorough trial—not for a few days or weeks, but for months. Early rising, early to bed, exercise, plain food, thorough and persevering continuance in gently-commenced training, the cultivation with resolute will of a cheerful temper, the society of friends and a certain number of hours spent every day in regular employment.

I am pleased to find myself so particularly represented! I’m really not a clerk, but I will claim to be a literary man, and will own up to being also a sedentary person, an idler, and arguably even a man of fortune.

There are many reasons to read a good fitness book, but very few reasons to read another after that. Walt Whitman’s fitness book isn’t really an exception. Still, if you are, like me, a connoisseur of fitness books, it’s worth including this one—for his unique prose style, for his place in American literary history, and for his perspective on manly beauty.