During the pandemic I followed something of a training plan—a mostly bodyweight exercise plan with minimal equipment beyond a pair of gymnastic rings, based largely on Anthony Arvanitakis’s Bodyweight Muscle books and YouTube channel.

Post-pandemic (once my local fitness room reopened, and exercise equipment became available again), more activities became possible. As they did, I added some in. With extra stuff to fit in, I let the program go. Instead I began exercising more intuitively—simply trying to fit in my strength training and my running as best I could. Each day I’d decide what to do influenced by how I felt, and what I’d done (or hadn’t done) the previous day or two, trying to cover all the bases, while allowing adequate time for recovery.

It has worked pretty well, but not as well as I was doing with an actual program. However, I don’t want to go back to the bodyweight rings program, because I feel like I’m getting real benefits out of the kettlebell and heavy club activities. So, I’m working on roughing up a training program that includes all the stuff I want to do.

Goals

It probably doesn’t make any sense to talk about the activities I do without thinking about the goals I’m trying to achieve.

Of course, I want to feel fit and healthy.

In the spirit of Peter Attia’s Centenarian Decathlon, I want to not only be capable of all the activities of daily living, but have enough reserve capacity now that I’ll still be able to do those things when I’m eighty, ninety, or (as I like to joke, except I’m totally serious) eleventy-one.

Among those things are the obvious—be able to hike a few miles on a rugged trail, climb a steep hill or several flights of stairs, carry a heavy bag of groceries home, put a suitcase in the overhead compartment, get down on the floor and back up again, etc. Besides those, I also want to be able to do well at longsword, which requires the ability to stand and walk in a low lunge, hold the sword with my arms at full extension (both forward and over my head), etc.

Fitness Activities

I figure the first step is just to document the activities that I think will support these goals, so that I know what I want to fit into the week. Here’s my first pass at a list. (Note that I already do an extensive warm-up every day, because it makes me move and feel better all day, whether I do a workout or not. I also walk my dog, and she rather insists on at least 6 miles a day.)

HEMA practice

My group has 2-hour meetings three times a week. They’re mostly skills training, so not too intense, although now that I’m approved for sparring the intensity has gone up.

Running

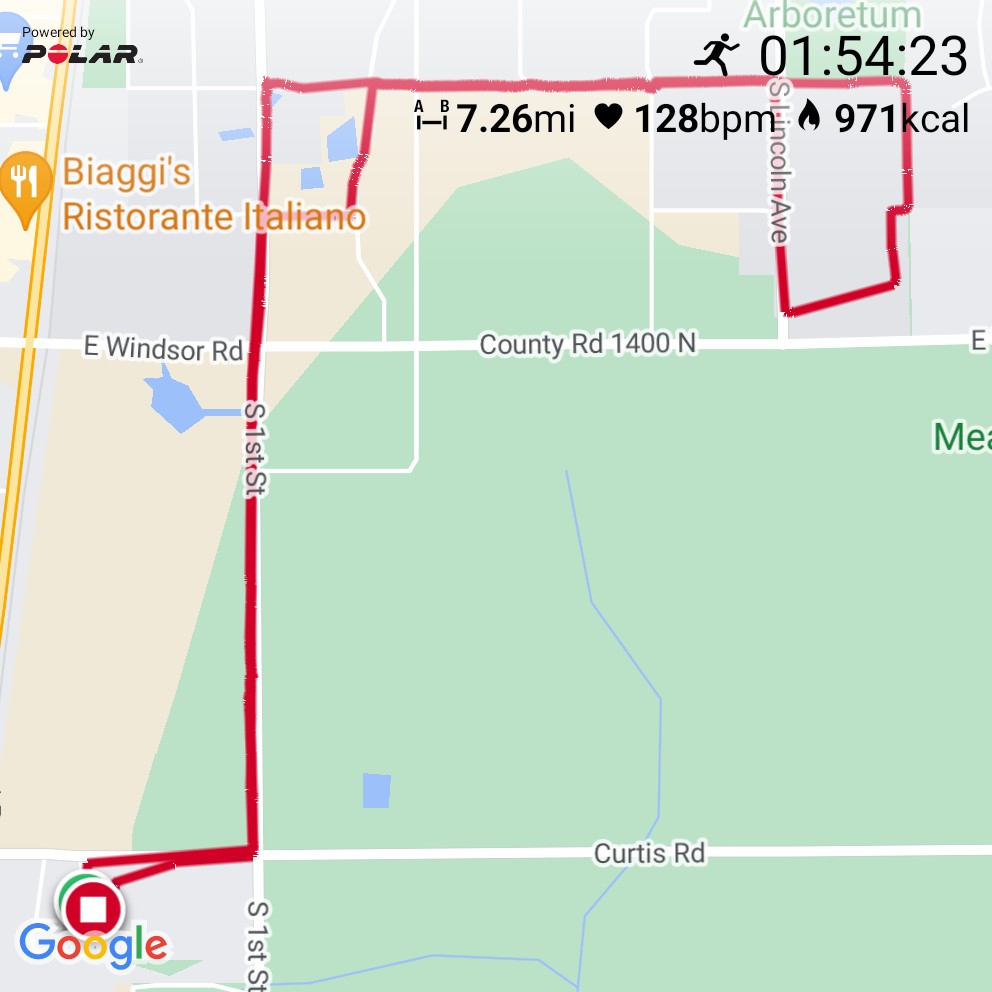

I want to go for two runs per week. One is a “long” run, in the 6–10 mile range (although I may want to work up to half-marathon length). The other is a “fast” run, which might include sprints, hill sprints, or just a hard run in the 3–4 mile range.

Kettlebell swings

This is primarily to work the muscles of my posterior chain, which needs a regular workout to keep me functioning well. In particular, I learned the hard way what happens if I don’t work my glutes. Currently I’m doing a heavy/light cycle, where I alternate between swinging an 18 kg (40 lb) kettlebell and a 24 kg (53 lb) kettlebell.

For the light kettlebell I’ve worked up to 10×19 swings emom. For the heavy kettlebell I’ve worked up to 10×12 swings emom. I try to add one swing per set every week.

Somewhere around sets of 25, I’d no longer get any break at the end of a minute. I don’t yet know if that’ll mean I’ll be able to do 250 straight swings.

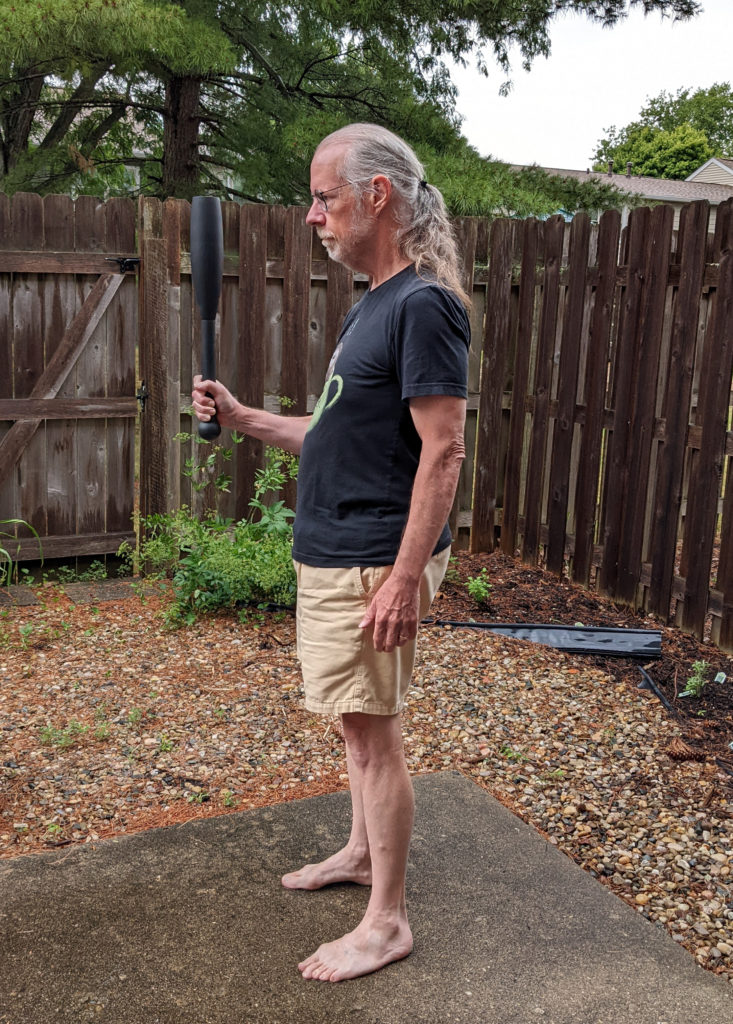

Heavy club swinging

This is one of my newer additions, and I have already seen it do great things for rotational strength, plus grip, arm, shoulder, and core strength. As the weight has gone up, it has started hitting the legs as well.

I do three exercises (outside circle, shield cast, inside circle) in sets of 5 left and 5 right, and I work up from 5 sets on each side, adding one set every workout or two, until I get to 10 or 12 sets on each side, and then go up in weight. I’m up 8 sets with a 13.75 pound club. Soon I’ll go up to 15 lbs.

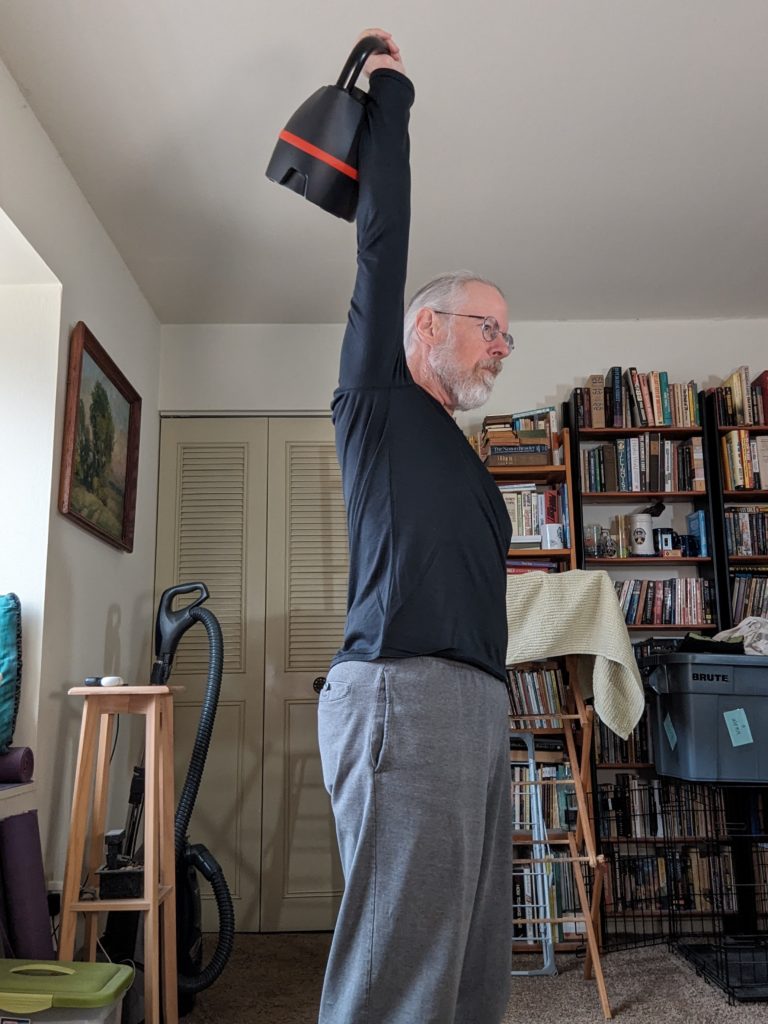

Kettlebell clean and press

This one seems especially useful for longsword, where you often need to hold the sword over your head, with your arms near full extension.

I do these as a reverse ladder, starting with 4 reps on the left and 4 reps on the right, then 3, then 2, then 1 rep on each side. Then I take a short break and repeat for some number of sets. Each workout (or every other workout) I add one set.

I just did 7 sets. I’ll work up to 10 or 12, then either increase the weight or else start the reverse ladder at 5 reps left and right, and go back to workouts of 4 or 5 sets.

Gymnastic rings circuit

Versions of this were my main workout all through the pandemic, when fitness rooms were closed and kettlebells impossible to come by. These were push/pull/legs workouts preceded by a starter and then ended with a core exercise. I had at least a couple variations of each exercise, so the starter was often jumping rope, but sometimes some sort of quadruped movement, push generally alternated between dips and some version of a push up, pull alternated between pull ups and inverted rows, legs was often air squats, but sometimes hindu squats or lunges or wall sits, and core was often hollowbody hold, but sometimes planks or reverse planks or V-ups.

I’d set the number of reps of each exercise at what I thought I could carry through for 3 rounds, and the 3rd round I’d aim to push to technical failure.

Toward a schedule

Putting all these things into a weekly schedule has proven to be difficult.

One issue is that my HEMA practice sessions occur at specific times, so there’s a certain lack of flexibility in the schedule there.

Besides that, there’s simply more stuff I want to do than fits easily into a week.

One solution to that would be to abandon the idea that “weekly” is the right structure. I could fit things into, let’s say, a 9-day cycle—but there are enough inconveniences with that, that every time I’ve considered it before, I’ve ended up sticking with weekly.

I’m pretty close to having a first cut at a weekly schedule ready to post. Look for it here in a day or two. (Update: It took much more than a day or two, but you can now see my Personal exercise program for winter 2023-2024.)