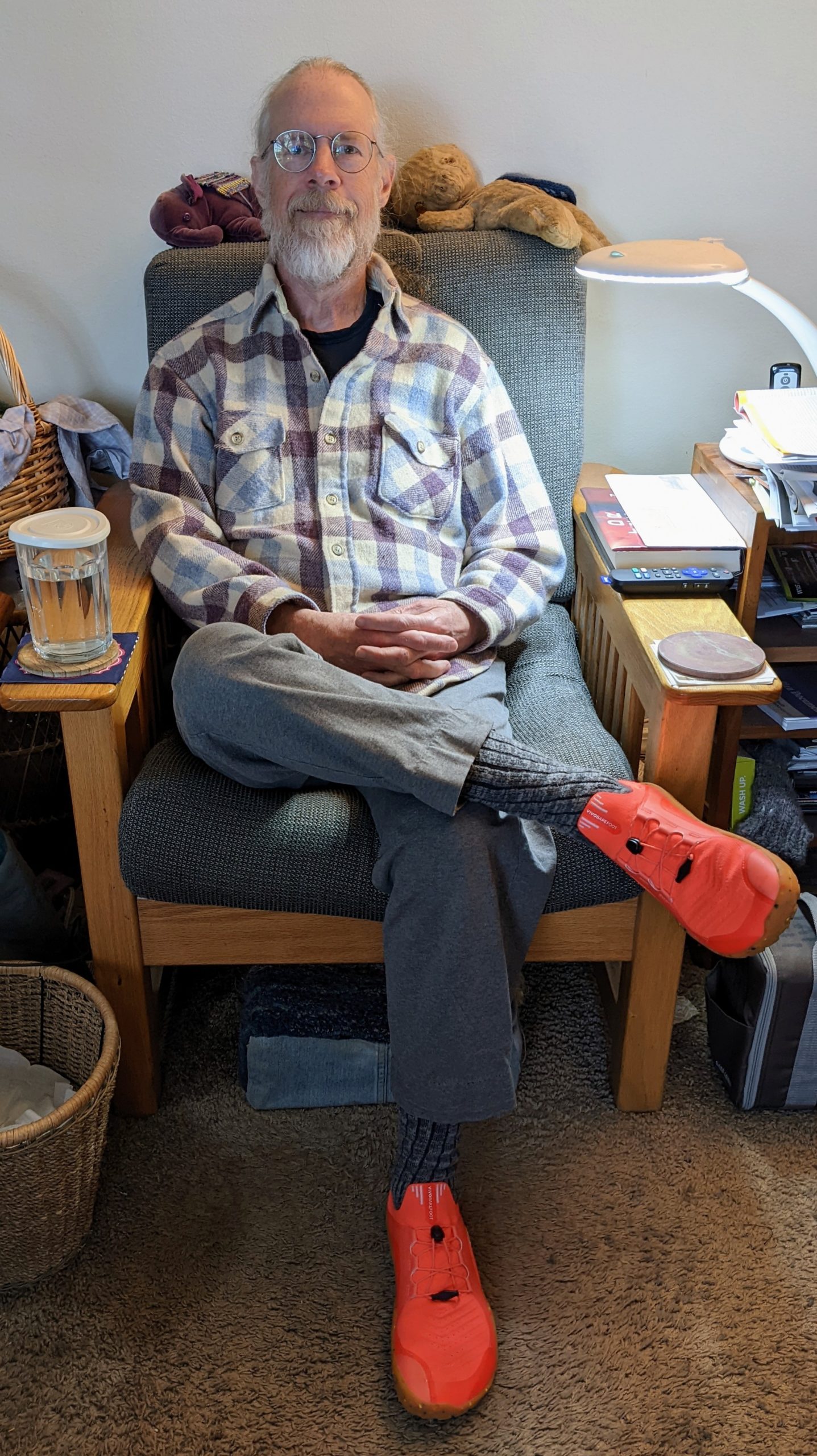

I have new shoes. They are very orange! (Vivobarefoot trail running shoes in Molten Lava.)

I have new shoes. They are very orange! (Vivobarefoot trail running shoes in Molten Lava.)

I’ve been meaning for a long time to write about the various minimal shoes that I wear these days, and since Xero recently gave me an affiliate link, now seems the perfect time.

First up is the Speed Force, which is Xero’s running shoe.

My experience with the Speed Force shoes is slightly fraught, because my pair arrived right after I aggravated a long-standing foot injury. To recover from the injury I ended up taking a long break from running, so these shoes have only recently started to get the wear-time they deserve.

Despite that unfortunate association, I really like these shoes. They’re the lightest, most minimal shoes I’ve got.

As part of my foot rehab, I’d did some actual barefoot running, which was highly effective: When I was actually barefoot, running didn’t aggravate my sore foot, whereas when I ran in shoes (even minimal ones), the injury would flare up again. That difference prompted me to remember that these shoes had a removable insole to provide just a tiny amount of cushioning. I took the insole out and that was the adjustment that got these shoes close enough to actually barefoot that I could start running again.

I’m sad that I missed almost the whole summer’s running, but I’ll make do with fall and winter running.

For me, these shoes provide exactly just what I want from minimal running shoes: Some puncture resistance and some thermal resistance. (They also provide some abrasion resistance—comfortable, but perhaps part of the reason my foot injury was so persistent. If you run with correct form there shouldn’t be any abrasion; protecting yourself from it just enables bad form, leading—at least in my case—to injury.)

The Speed Force shoes are the maximally minimal shoes I had been looking for. Check them out at my affiliate link. Buy a pair (or any of the other Xero shoes) and earn me a tiny pittance!

There are several other Xero shoes, boots, and sandals that I wear regularly, which I’ll write about over the next little while.

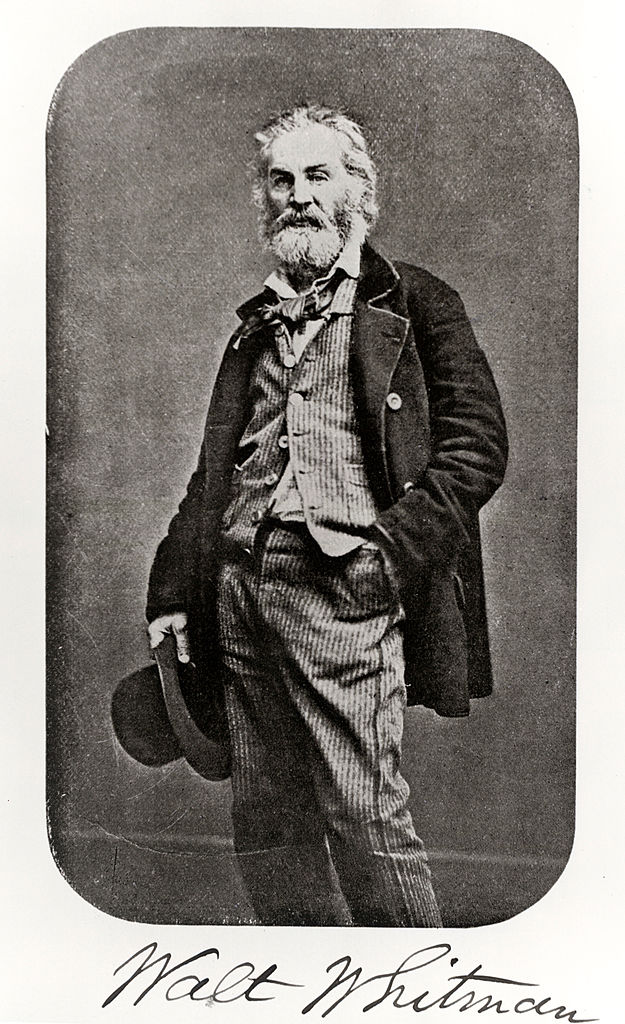

I actually knew this already, having seen an article about the work, originally serialized in the weekly journal the New York Atlas under the pseudonym Mose Velsor, when it was collected and republished as a PDF (Manly Health and Training) in 2016. But I hadn’t read through the whole thing until this month.

I’ve read a lot of fitness books over the years, and one thing I find interesting is how much they are all the same—including Walt Whitman’s. Of course, every fitness book has its own peculiarities—more or less focus on functional fitness, flexibility, muscle size, body fat, strength, quickness, power, control, aerobic capacity, aesthetics, etc. But the levers available to affect these things don’t really change: sleep, diet, resistance exercise, endurance training, and stretching just about cover the gamut. Aside from the details of the diet, it’s primarily a matter of selection, focus, and combining of exercises.

Walt Whitman’s fitness manual offers a nice little selection of exercises, none of which would seem out-of-place in any modern fitness book:

Walt Whitman wants his readers to be exemplars of manly beauty. In fact, based on how he talks about it, you have to assume that increasing the amount of manly beauty around is really the most important thing he hopes to achieve with his book—but that’s a fair thing to do, because:

As regards human beings, in an important sense, Beauty is simply health and a sound physique. We can hardly conceive of a man, at any age of life, who is in perfect health, and keeps his person clean and neatly attired, who has not some claims to this much-prized attribute.

Related to this, he is clearly keen to normalize men caring about aesthetics:

Nor is there anything to be ashamed of in the ambition of a man to have a handsome physique, a fine body, clear complexion, nimble movements, and be full of manly vigor. Ashamed of! Why, we think it ought to be one of the first lessons taught to the boy, when he begins to be taught at all. It is of quite as much importance as any grammar, geography, or arithmetic— indeed, we should say it was of unrivalled importance.

Of course, some things are desirable for more than just their aesthetic benefits:

The beard is a great sanitary protection to the throat—for purposes of health it should always be worn, just as much as the hair of the head should be. Think what would be the result if the hair of the head should be carefully scraped off three or four times a week with the razor! Of course, the additional aches, neuralgias, colds, &c., would be immense. Well, it is just as bad with removing the natural protection of the neck; for nature indicates the necessity of that covering there, for full and sufficient reasons.

An aside, because it touches on both dancing and aesthetics: A few years ago I read a fitness book titled something like How to Have a Dancer’s Body, which I read hoping to get some suggestions for improving strength and flexibility, only to be sadly disappointed. Its advice in those areas, after a brief treatment of stretching and posture, was that the student should find a good dance class and workout under a teacher. (Most of the book seemed to be about normalizing having an eating disorder—which, admittedly, is probably essential if you want to have the body of a prima ballerina.)

Dance’s attractiveness comes, I think, from the way it both provides actual (often astonishing) physical capability along with an aesthetic that I and many other people find attractive. Walt agreed on both counts, although seemed to take issue with the dance fashions of the times:

As originally intended, dancing was meant to give harmonious movements to the whole body, from the legs, by keeping time to music. In that sense, it was a beautiful art, and one of the noblest of gymnastic exercises. Modern arrangements have made it something quite different.

We would be glad to see some manly genius arise among the dancing teachers, who, out of such hints as we have hastily written, would assist the objects of the trainer and gymnast.

As I said, all fitness books are pretty much the same, so I am not really surprised to find things here that read exactly like something I might find in some entirely modern source of fitness advice.

For example, his rant on shoes and feet sounds exactly like what you might expect if Walt Whitman wrote some copy for Katy Bowman’s Nutritious Movement shoe page or Steven Sashen’s Xero Shoes.

Probably, in civilized life, half the men have more or less deformed feet, from the tight and wretchedly made boots generally worn.

In one of the feet there are thirty-six bones, and the same number of joints, continually playing in locomotion, and needing always a free and loose action. Yet they are always squeezed into boots not modeled from them, nor allowing the play and ease they require. For the modern boot is formed on a dandified idea of beauty, as it is understood at Paris and London, and not as it is exemplified by nature.

If you want to see the feet in their natural and beautiful proportions, you must get a view of the casts of the remains of ancient sculpture, representing the human form, doubtless from the best specimens afforded by the public games and training exercises of the Greek and Roman arenas. They exhibit what the foot is when allowed to grow up, with its free, uncramped, undeformed action. There have been no artificial coverings or compressions; and we know that the gait therefrom must have been firm and elastic. We can understand how the Macedonian phalanx, or the Roman legion, performed its long day’s march. We can see the ten thousand Greeks pursuing their daily wearying course through the destroying climate of Asia, marching firmly, manfully, across the arid sand, the mountain pass, or the flinty plain. It is a truthful lesson we may learn, not for the soldier only, but for the civilian.

Probably there is no way to have good and easy boots or shoes, except to have lasts modeled exactly to the shape of the feet. This is well worth doing. Hundreds of times the cost of it are yearly spent in idle gratifications—while this, rightly looked upon, is indispensable to comfort and health.

Simlarly, his principle workout plan sounds exactly like a MovNat combo:

In truth, however, a man who is disposed to attend to the matter of strengthening and developing his muscular power, will be continually finding some means to further that object, and will do so in the simplest manner, as well as any. To toss a stone in the air from one hand and catch it in the other as you walk along, for half an hour or an hour at a stretch—to push and roll over, a similar length of time, some small rock with the foot, thus developing the strength of the knees and the ankles and muscles of the calf—to throw forward the arms, with vigorous motion, and then extend them or lift them upward—to pummel some imaginary foe, with stroke after stroke from the doubled fists, given with a will—to place the body in position occasionally, for a moment, with all the sinews of the arms and legs strained to their utmost tension—to take very long strides rapidly forward, and then, more slowly and carefully, backward—to clap the palms of the hands on the hips and simply jump straight up, two or three minutes at a time—to stand on a hill or shore and throw stones, sometimes horizontally, sometimes perpendicularly— to spring over a fence, and then back again, and then again and again—to climb trees in the woods, or gripe the low branches with your hands and swing backward and forward—to run, or rapidly walk, or skip or leap along—these, and dozens more of simple contrivances, are at hand for every one—all good, all conducive to manly health, dexterity, and development, and, for many, preferable to the organized gymnasium, because they are not restricted to place or time. Nor let the reader be afraid of these because they are simple, but form the daily habit of some of them, without making himself uneasy “how it will look” to outsiders, or what they will say.

The book especially addresses people who are in school, telling them to be “also a student of the body,” but wants to be sure that the reader knows that not only students are the intended audience:

To you, clerk, literary man, sedentary person, man of fortune, idler, the same advice. Up! The world (perhaps you now look upon it with pallid and disgusted eyes) is full of zest and beauty for you, if you approach it in the right spirit! Out in the morning! Give our advice a thorough trial—not for a few days or weeks, but for months. Early rising, early to bed, exercise, plain food, thorough and persevering continuance in gently-commenced training, the cultivation with resolute will of a cheerful temper, the society of friends and a certain number of hours spent every day in regular employment.

I am pleased to find myself so particularly represented! I’m really not a clerk, but I will claim to be a literary man, and will own up to being also a sedentary person, an idler, and arguably even a man of fortune.

There are many reasons to read a good fitness book, but very few reasons to read another after that. Walt Whitman’s fitness book isn’t really an exception. Still, if you are, like me, a connoisseur of fitness books, it’s worth including this one—for his unique prose style, for his place in American literary history, and for his perspective on manly beauty.

I don’t always dream about shoes. But when I do, they are (apparently) brogues.

Jackie and I went for a nice walk yesterday, through the prairie and woods next to Winfield Village. We walked about four miles altogether.

Toward the end of the walk I paused to retie a boot, and found that my back was really tight. Bending down caused pain in my sacroiliac joints.

It was odd because it was a familiar sensation, but an old familiar sensation. I used to feel that pretty often on a long walk, but I hadn’t felt it lately. Without really thinking about it, I had attributed the change to general improvements in fitness and flexibility. But here after a fairly short walk that old pain was back again.

I was briefly puzzled, but realized right away what had happened: Because the walk was going to be wet and muddy, I’d worn my old heavily lugged goretex hiking boots.

These used to be my main boots; they’re the ones I wore on my 33-mile Kal-Haven Trail hike. I’ve kept them because I haven’t found a satisfactory pair of waterproof minimal boots, and I’ve worn them right along over the three or four years I’ve been transitioning to minimalist footwear, whenever I needed waterproofness or a heavily lugged sole. But they have the big downsides of non-minimalists shoes: Their thicker heel jacks up my posture, and their rigid sole keeps my feet from adapting to the terrain.

It might not be just the footwear. The trail was muddy enough that every step was a bit of an adventure—my foot would sink into the ground, but it would sink a different amount each step, making it hard to establish and maintain a consistent gait. I wouldn’t be surprised if that didn’t play into making my back feel a bit wonky after a couple of miles.

But clearly it’s time to retire these old boots and find some waterproof minimalist boots with sufficiently lugged soles to handle some short, steep hills on a muddy trail.

If you’ve got any suggestions, I’d be glad to hear them. Comment below, or send me email! (Email address on my contact page.)

I was generally pleased with the Merrill Road Glove shoes that I bought last summer, but they didn’t offer quite enough protection for running on gravel. Because of that, I largely quit running on the gravel road around Kaufman Lake, which had been my standard short run.

To expand my trail-running options for this year, I bought a pair of Trail Glove shoes. Today was my first chance to give them a try, and of course I did my old 1.5 mile Kaufman Lake loop.

It was a good run. I felt comfortable all the way through—no ankle or knee pain. I finished with some energy left, enough that I’m sure I’ll have no trouble running the 2.2 mile Centennial Park loop that served as my standard short run for the second half of last summer. I managed a 11:26 pace, solidly in the mainstream of last year’s runs.

I’m not quite where I hoped I’d be, because I just couldn’t bring myself to put in the miles on the treadmill. I did okay in the first half of the winter, but in the second half, I barely ran at all. Because of that, I’ll have to be somewhat cautious ramping up the distance. I have no doubts about 2.2 miles, but I’ll run that a couple of times before attempting longer distances. I ran almost 6 miles as recently as December, so expect I can recover the capability of running that distance again pretty quickly, but I don’t want to injure myself. Hence: caution.

Still, a good start.

The Trail Glove shoes worked fine—provided adequate protection against hard/sharp rocks while keeping most of the “barefoot” feel of the Road Glove shoes.

One risk: The forecast is for 6 straight days of nice running weather. I’ll need to take a couple of those days as rest days, which may be hard to do.

I knew I’d have to run some low-mileage days, after switching to minimalist shoes and changing my gait (to land on my forefoot instead of my heel). As it turns out, the changes have been more drastic than I’d expected.

With one exception, the changes have all been good. My new running gait feels good and it’s more gentle on my feet, ankles, and Achilles tendons. It’s also faster. I’m not sure yet, but I think it may well turn out to be a lot faster.

The one exception is that running this way instantly destroyed my old running gait.

As I said, I had to cut my mileage quite a bit, and I’d hoped to ameliorate that by doing one long run in my old shoes with the old gait. And I did, sort of: on Sunday I ran 3.1 miles in my old shoes. It was a terrible run. I felt awkward and sluggish and uncomfortable the whole way.

The reason for the reduced mileage is that the new gait really works my calves. They get sore, and I need to take a rest day to recover. After doing 1.5 miles on Thursday last week, I had to take two days off to recover. Then I ran 2.15 miles on Monday, and had to take Tuesday off.

But I discovered something toward the end of Monday’s run: this new gait feels better—and is gentler on my calves—when I run faster.

Much the same was true of my old gait. Each new running season I’d look forward to the day when I could stretch out and run at a more natural pace that was gentler on my legs than the cramped stride I’d resort to early in the season when I could barely run for 20 minutes.

The same seemed to be true of barefoot running. I picked up the pace for the last block or so on Monday, and when I ran faster, it felt a lot better.

So, I made today a tempo run. Basically, I ran my ordinary 1.5-mile short loop, but I ran pretty hard.

Six weeks ago, I did a tempo run where I was hoping to break 17 minutes for my 1.5 run, and was delighted to clobber 17 minutes, finishing in 16:16.

With six more weeks of training, I was not surprised to break 16 minutes. But I was surprised that once again I clobbered it: I did my 1.5-mile short loop in 15:08.

That is, by 49 seconds, the fastest I’ve every run this route. I’ve run faster (this was a 10:06 pace), but only on a track, and only over 1 mile.

Of course, now my calves are sore. I’ll probably have to take a rest day tomorrow—maybe two—and stick with shortish runs for a while longer. But I’ll be doing long runs soon. And I’ll be doing them a lot faster.

I decided that I wanted to try barefoot running.

Of course, I didn’t want to actually run with bare feet. That seems stupid (although I suppose it’s another capability that might be worth developing, just in case circumstances arise where I might really need to run in bare feet).

No, what I wanted to do—like many people who have read Christopher McDougall‘s book Born to Run—was try running with the stride that one would use if one were barefoot.

The natural running stride, it turns out, is quite different from the walking stride. In walking, you land on your heel, then rock forward and push off with your toes. If you wear cushiony, padded running shoes, you can run like that too, but it’s not the natural way to run.

The natural running stride is easy to experience—just run in place for a few seconds. You’ll land on your forefoot, absorb the impact with the muscles of your calf and thigh, and then launch yourself off again with those same muscles.

I’ve been trying to run with more of a forefoot strike since I started running again this spring, but it’s hard to do if you’re wearing ordinary running shoes. The heel is not only all cushiony, it’s thick. That means that, unless you exaggerate your forefoot strike, you’re still going to land on your heel.

So, I went to the shoe store, meaning to try out one of the many new “minimalist” running shoes with thinner heels and less cushioning that are now on the market.

Happily, we have a great running shoe store in town called Body and Sole. After trying on three pairs of shoes with progressively less padding and structure, I tried on a really minimalist pair, which felt wonderful. I tested them in the concrete parking lot, taking a turn around the outside of the building, and then a second turn, and then a third. I told the salesman, “That first pair was fine, and I would have bought them. But this pair was the pair that made me want to keep running laps around the building.”

So, now I need to adjust to this new stride. It demands a bit more strength and endurance in the calf muscles (and no doubt in the muscles that keep the bones of the foot correctly arranged as well).

The shoes I ended up, a style called the Road Glove, are made by Merrell, which also provides an extensive website on barefoot running. They feel just like you’re barefoot, except that there’s a sole to protect your feet from sharp/hard/abrasive road hazards.

Following their advice, I just ran half a mile yesterday. I certainly feel it in my calves today. They don’t feel bad, though. Just tired and sore like I got a good workout yesterday. And my tendons and joints don’t feel sore at all.

The timing is perfect for doing a few low-mileage days. On Sunday I ran 5.25 miles for my long run (in my old shoes), so Monday and Tuesday would have been light running days anyway.

Plus, on Tuesday we went for a long bike ride. We rode to Philo and met some friends for lunch at the Philo Tavern. That’s a 28-mile round trip, which we did in an even three hours. (I wrote about an earlier bike ride to Philo in my old Clarion journal.)

Here’s us, on the road to Philo:

And here’s a pretty ladybug that I noticed while we were paused to get that picture:

I’ve already sent that picture to the Lost Ladybug Project, which is trying to gather data on the native ladybugs, whose distribution is changing due to the importation of non-native ladybugs and climate change.

I don’t hate shopping. I sometimes say I do, but it’s an inaccurate shorthand. What I hate are a cluster of things inextricably intertwined with shopping. I hate driving from store to store. I hate the mall. I hate agonizing about the tradeoffs between choice A and choice B, especially under time pressure, and especially under conditions of imperfect information.

I don’t hate shopping. I sometimes say I do, but it’s an inaccurate shorthand. What I hate are a cluster of things inextricably intertwined with shopping. I hate driving from store to store. I hate the mall. I hate agonizing about the tradeoffs between choice A and choice B, especially under time pressure, and especially under conditions of imperfect information.

I’m a lot happier buying stuff on-line. But not boots. I never buy shoes or boots without trying them on.

I also dislike spending money, especially spending largish sums of money, such as the $168 (including tax) that I just spent for a pair of boots.

I think I like the boots. I wanted a pair of waterproof, lightly insulated, hiking boots. This pair is all those things, plus they fit well and feel good on my feet. I’d had in my mind that I’d get GoreTex waterproofing and that the degree of insulation I wanted would probably be 200 gm Thinsulate, and I didn’t end up getting either of those. These are just “waterproof,” which probably means that the leather was treated with some sort of sealant—probably adequate for my purposes. And they’re insulated with 200 gm Primaloft, which is also probably at least as good as Thinsulate.

I decided that I needed these boots, because last year I found myself staying indoors too much during the winter, because I didn’t have adequate footwear for cold and wet. (We get a lot of cold and wet in Central Illinois—slush, snow, rain changing to snow, melting snow, cold rain falling on snow or ice, freezing rain, freezing mist. If you can think of weather that’s cold and wet, we have it here.)

With the right boots, I’m hoping I’ll be able to get myself out to walk, even in inclement conditions. Plus, there’s the slight extra boost that comes from the novelty factor of new boots.

And, with that in mind, I’m heading out now to walk a mile or two, to start breaking them in.