Who knew that Albrecht Dürer wrote—and illustrated!—his own fencing manual? I ordered a copy of Dürer’s Fight Book: The Genius of the German Renaissance and His Combat Treatise.

It predates Meyer, and covers wrestling, dagger, longsword, and messer.

Who knew that Albrecht Dürer wrote—and illustrated!—his own fencing manual? I ordered a copy of Dürer’s Fight Book: The Genius of the German Renaissance and His Combat Treatise.

It predates Meyer, and covers wrestling, dagger, longsword, and messer.

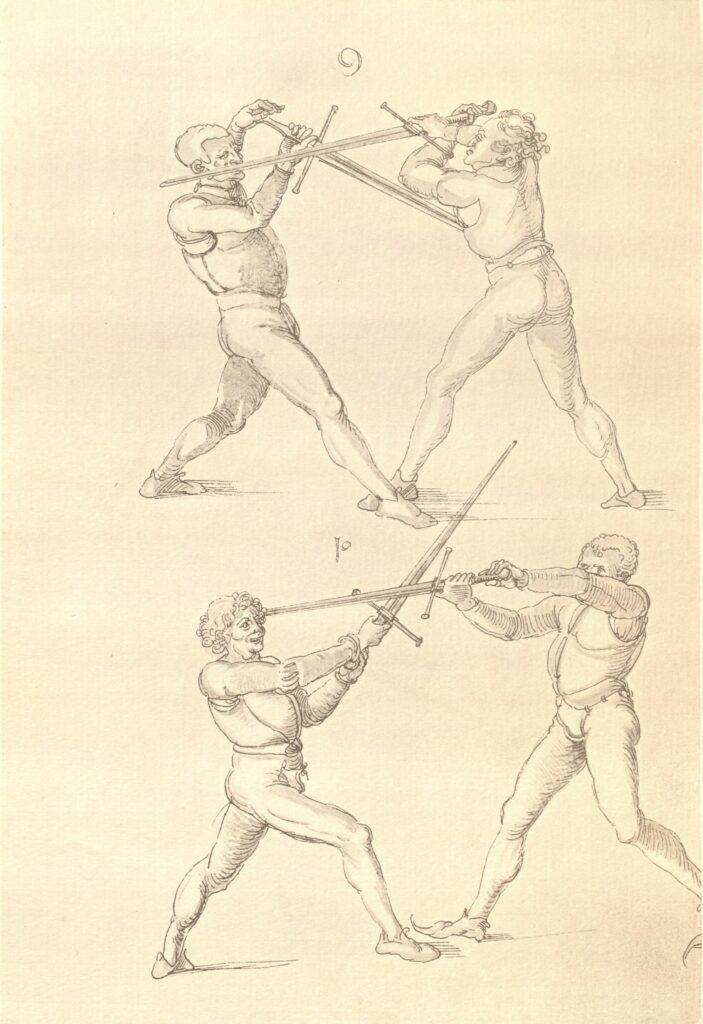

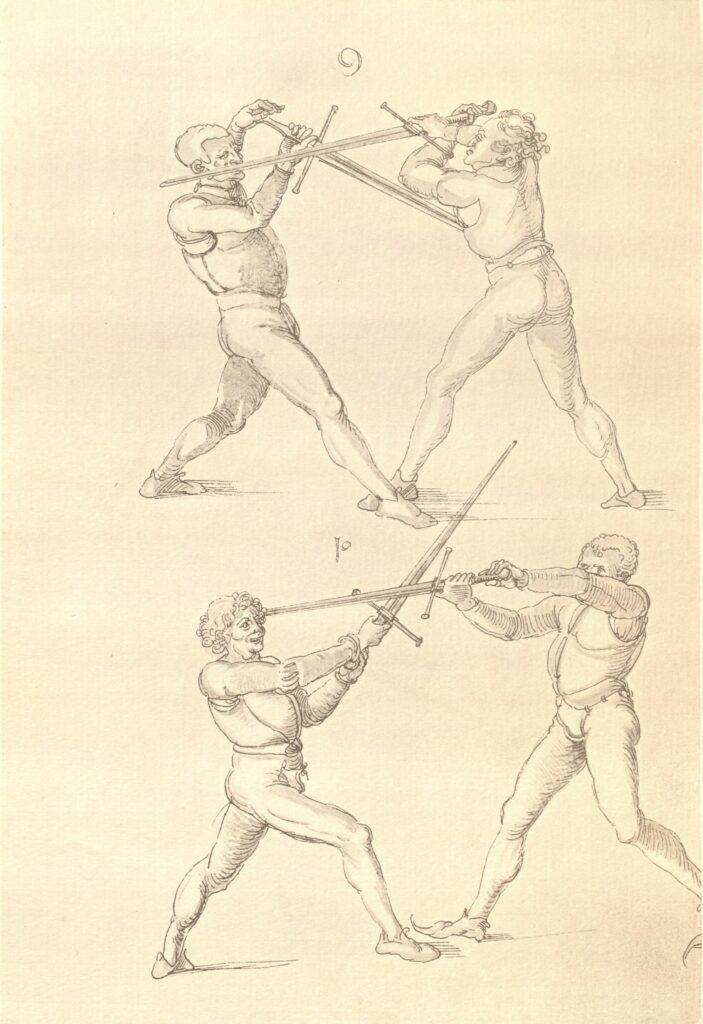

A couple of aspects of longsword turn out to be hard not from a skill perspective, but from a simple strength and endurance perspective. Look at the guys in this picture. Their arms are fully extended, either forward or upward. That’s just hard to do for minutes at a time. Besides that, they’re in a pretty low lunge position. That’s also hard to do for minutes at a time.

A couple of days ago, I had a chance to ask celebrity trainer Mark Wildman how he’d program for building arm strength and endurance. It turns out he’s a huge longsword geek. Here’s the video, cued up to where he reads my question (should be 41:57). The related stuff goes through 48:50).

My original question was: “I’m doing longsword. One issue is arm strength and endurance. I’m doing kettlebell clean&press and pushups (for holding the sword overhead and extended forward). Any other ideas?”

Here are my notes on Mark’s reply:

Mace & Club

Single-arm heavy club program (a program that isn’t for sale yet, but that is pretty easy to deduce from the videos on Mark Wildman’s youtube channel).

Basis of Strength (2-Handed club program that does exist, although it’s pretty expensive).

Mace 360s. (The mace equivalent of a club shield cast: You bring your hand past your opposite ear, swing the mace behind you, and catch it back in front.)

Cut the Meyer square for time. (I don’t think he said WHAT time would be appropriate. Maybe do a 10-minute emom, where you do the full square, rest until the end of the minute, and then repeat. Or maybe 30 seconds on/30 seconds off.)

He emphasized training both dominant hand and non-dominant hand.

This, by the way, goes against the advice of Liechtenauer, who says:

Fence not from left when you are right. If with your left is how you fight, You'll fence much weaker from the right.

I suspect that the difference has to do with your goals. Liechtenauer was speaking to someone who had to win sword fights. Wildman is speaking to someone trying to get fit for a hobby.

Push ups as part of a warm-up. (Since I had mentioned pushups.)

Instead of pushups, do burpies in full HEMA gear. (Oy.)

Don’t do actual sword movements with mace or club. Do those with an actual longsword.

Mace drop swing in Meyer stance (4 versions: contra- and ipso- lateral with each foot forward): Here’s two videos of that:

I’ve ordered a mace so I can try that (and other mace stuff). I haven’t yet pulled the trigger on the (expensive) Basis of Strength program, although I’m tempted. While I ponder that, I’ll start doing mace drop swings while in a lunge, and see if I can get both my extended arm strength and endurance up, while also improving my Meyer fencing stance.

I’ve been training in longsword for almost a full year now—I just looked and saw that my first two classes were in the last week of March last year—and I’d gotten kind of discouraged. I did okay the first few weeks, but then plateaued. For months I felt like I was making no progress at all. Finally, on Thursday, I felt like I had taken a step forward.

I’ve come up with training-at-home plans a couple of times in the past year, thinking that I need to work out my Meyer stance (very low lunge, with the front thigh almost parallel to the ground), and of course my cuts. (This pictures shows me doing a zwerchhau, and the cut looks pretty okay, although the stance isn’t nearly low enough.) That is, I’d come up with the plans, but I largely hadn’t followed through. Today, with the encouragement of having done okay on Thursday, I got out with my sword and spent a while working on low stance, Meyer square cuts, and zwerchhaus.

Several members have done a “bear pit” for their birthdays: The birthday boy faces everyone in the group for a pass or three, one after another. The exact details vary, but the idea is to pick some metric (passes or opponents) and do enough to hit your age. I’ll turn 65 in mid-June, and I’d like to be able to carry on the tradition. I think I’m within striking distance on the basic fitness. (I was doing 2-hour runs at the end of last summer, and my last run was 1 hour 14 minute.) But it wouldn’t be much fun to face opponent after opponent and get beat every time, so I’m pleased to finally feel like I’m making some progress.

If you’re local, and you think swords are cool (and who doesn’t?), you might check out our group: Tempered Mettle Historical Fencing.

My copy of the new translation of Meyer’s 1570 sword-fighting treatise has arrived!

In my workout yesterday, in the “lower body” slot where I’d usually do either some type of squat or some type of lunge, I decided to practice stepping for longsword fencing. As soon as I started, I realized there was all sorts of nuance to how to do it, with a lot of details I wasn’t sure of.

I posted a question to the group discord, asking when to pivot the foot. (That is, the front foot is pointed straight ahead and the back foot is turned out 45 to 90 degrees. After you step forward with your back foot it’s easy enough to just put it down pointed straight ahead. But your new back foot needs to turn out at some point.) I also wanted to know whether people did a toe-pivot or a heel-pivot.

A couple of people responded to say that they did toe-pivots, and that they did them at the end, after establishing the new front foot. Good to know.

When I got to today’s class, Christopher Lee French (one of the intermediate HEMA students, but also an instructor in sport fencing at The Point Fencing Club & School of Champaign) gave me a whole master-class in stepping. He made a series of excellent points.

(Let me pause just for a moment here to make it clear that all the following is my understanding informed by what he was telling me. It’s certainly not his fault if I’ve gotten some things wrong here.)

Here’s a short list:

He demonstrated many of these, and his example steps also helped me make sense of the (to me) odd use of a toe-pivot described by others in the discord. He tended to finish a quick step with his back foot not yet pointed out. Instead it was pointed forward, with the heel off the ground. When I asked about why he wasn’t turning it out, he said, “Fix that when you have time.” And the way you’d fix it would be to do a toe pivot, and then put your heel down.

None of this really has much to do with Meyer’s text. That is, I’m not trying to figure out how to step. Rather, I’m thinking about what to train to be able to execute what Meyer’s text documents.

Specificity would suggest that the way to train for fast, smooth, even steps would be a lot of stepping. But I know from experience that it’s always worth breaking these things down and checking to see if any of the pieces is posing a limitation.

To pick a not-so-random example, I’m limited by my leg strength for single-leg standing in a very low stance. Things to train for leg strength with bent knees: wall sits, single-leg wall sits, single-leg standing. Those first two I’ve done before, but I can emphasize them a bit for a while. I can add some bent-knee single-leg standing. And, because specificity is still a thing, I’ll also practice executing passing steps and gathering steps as smoothly and rapidly as possible.

In class a couple of nights ago the lesson was for us to take our first stab at understanding a piece of the text from Joachim Meyer’s The Art of Combat.

I’ve ordered a copy of the book. It hasn’t arrived yet (being shipped from England), but here’s a different translation of the same text from the Wiktenauer site:

Slicing

Is a fundamental element of proper handwork, when you rush from your opponent with quick and agile blows, you can block and impede him better with no other move than with the slice, which you, though you will treasure it in all instances as special as here, will hold in reserve. You must however complete the slices thus: after you entangle your opponent’s sword with the bind, you shall strive thereon, feel if he would withdraw or flow off from the bind, as soon as he flows off, drive against him with the long edge on his arm, thrust the strong or quillons from you in the effort, let fly, and as he himself seeks to retrieve, strike then to the next opening.

https://wiktenauer.com/wiki/Joachim_Meyer, “Of Displacing,” Slicing

The text we used translated what is here as “flow off” as “strike around,” which is actually a specific move (striking first to one side and then to the other). The translation included the word “pursue,” I think where this one says “drive against.”

I generally think of myself as being pretty good at working with text, but I found this remarkably difficult.

The correct move, the instructor indicated, was that you should not wait for the “flow around” or “strike around” to proceed, but rather “as soon as” he begins the move, “drive against” or “pursue” by thrusting your sword forward so that the guard of your sword is pressed up against his.

Since you caught him early in striking around, this leaves him in a very awkward position, giving you many options for striking him effectively.

This all makes sense, but I did not get it from my first ten readings of the text. Clearly I’m going to have to spend a lot of time and effort making sense of it, if I’m going to get good at this.

In our practice session, we did not have the picture:

I think I see this move in the middle bit, where the guards of the swords are pressed together.

The most obvious goal for someone learning to fight with swords is to get good enough to enter sword-fighting competitions and do well against other sword-fighters. And, I suppose that is my long-term plan. My medium-term plan is less ambitious, but rather specific.

I’ve come up with this intermediate goal because I know that I am not a natural martial artist. My reflexes and hand-to-eye coordination are merely average. Besides that, I am well below average in my ability to watch someone execute a move and then do “the same thing.” I’ve written about this before in my post Learning movement through words.

I hadn’t realized it in advance, but the very nature of Historical European Martial Arts makes it especially well-suited to me: Essentially every HEMA practice is based on a text—in our case Joachim Meyer’s The Art of Combat. The text provides the verbal description that I need to be able to learn a movement practice.

Still, even with the text and the instructors showing us stuff (and correcting our errors) and classmates to practice with, I’m still the guy with merely average reflexes and hand-to-eye coordination (plus a lifetime of no experience with stuff like this, because I was in my 40s before I figured out that I could learn this stuff at all, as long as I have a verbal description to work from), so my expectations for developing the skills of an excellent sword-fighter are rather low.

That would be rather discouraging, so I’ve come up with my own personal medium-term goal. I’m going to focus on executing Meyer’s system very, very well. Success for me will not depend on doing well sparring with opponents, but rather on looking like—moving like—someone who has trained with the best teachers of Meyer’s system.

Expressed in aspirational terms: A year or two from now a modern expert in Meyer longsword will look at me and think, “Wow—this guy looks like he might have trained with Meyer himself!”

Knowing my own strengths and weakness, this seems like it might be achievable, with the bonus that it will probably be much more effective at making be a better sword-fighter than if I jumped right into trying to figure out how to spar well.

I had been waiting to get the new translation of Meyer that’s coming later this month from HEMA Bookshelf, but decided to go ahead and order a copy of the existing translation. It’s what everyone in the group has been working with for several years now, so the instructors and senior students all know it. I’m sure it’ll remain a useful reference even if everyone switches to the new translation as soon as it’s available. (And I’ll get the new translation immediately myself.)

My short-term plan to support my medium-term plan will be to create my own practice sessions on the foundational stuff: stance, footwork, guards, and cuts. The classes covered stance and footwork on the first day (and then added a third stepping pattern on the second day), but hasn’t returned to those things since then. This makes sense: We’re practicing stance and stepping as we’re learning cuts and parries. But for my purposes, I think and extra 15 or 20 minutes each day specifically working on these items (which are readily amenable to solo practice) will do me a world of good. I’ll also spend a few minutes each day working on the German vocabulary, so I know the names of everything (and know what the thing is!).

One bright spot: I seem to be fit enough. The first week and a half I was just a bit worried about whether I could do a 2-hour training sessions and the recover enough to do the next one and then the one after that, but it seems that my fitness regimen of the past few years is standing me in good stead. I may not be as strong or as fast (or recover as well) as the fitter of the college-age kids, but I’m fit enough to see a practice session through to the end.

If you don’t want to get hit with a sword, you might want to consider a different hobby.

My instructor at yesterday’s HEMA class.