Ooh! My new story has picked up a review! https://www.goodreads.com/review/show/5404239594?book_show_action=false

You can buy the story here: https://waterdragonpublishing.com/product/classic-beginners-mistake/

Ooh! My new story has picked up a review! https://www.goodreads.com/review/show/5404239594?book_show_action=false

You can buy the story here: https://waterdragonpublishing.com/product/classic-beginners-mistake/

I’ve long struggled to program my training, a task that is difficult because I want to get better at everything. I want to be stronger and faster. I want to have more endurance for running and more endurance for walking (which turn out not to carry over perfectly from one to the other). I want to maintain and deepen my taiji practice and my parkour practice. I want to learn rock climbing and fencing.

This isn’t a new problem for me. As just one example, back in 2013 I was considering programming training not organized by the week but perhaps in 9-day training cycles.

There are at least two problems that I’m trying to address. One is just fitting in training for each capability I want to get better at. The other is how to not break down under that training load (which involves at least fitting in enough recovery time, but other stuff as well).

During the pandemic I’ve done okay, by focusing on exercise. Although I tweak things pretty often, very roughly I’ve organized each week to include:

That looks pretty good until you do the math and see that it only works for 8-day weeks.

Besides that, note that this excludes my taiji practice (which amounted to more than 5 hours a week back in pre-pandemic days, because besides teaching I was engaging in my own practice). It also excludes my long, slow warmups (which I’ve started calling my “morning exercises,” since I do them pretty much every morning before proceeding with my “workout” for the day).

The way I’ve been making it sort-of work is by doubling up how I think about some of the workouts. A “fast” run with sprint intervals is a HIIT workout, and a HIIT workout with kettlebell swings is a strength-training session.

Still, there’s no hope to make something like this work if I want to add in parkour, rock climbing, and fencing. Likewise, I know from experience that I need a full day to recover from a very long (14-mile or longer) walk, so doing one of those requires devoting two days out of the week to just one training session.

So, I’m left in a quandary. How can I get better at all the things I already do and add in some additional activities as well? (Just before the pandemic I’d started taking an aikido class; I’m sure I’d enjoy finding a local group that plays Ultimate Frisbee….)

Happily for me, Adam Sinicki (aka The Bioneer) has written a book that addresses exactly this issue. The book is Functional Training and Beyond: Building the Ultimate Superfunctional Body and Mind. It starts out talking about “functional training,” and about the history of “getting in shape” i.e. “physical culture.” Then it runs though all the most common training modalities (bodybuilding, powerlifting, kettlebells, crossfit, etc.), before proceeding to talk specifically about how to take the best from each one, and then how to program it all into a workout plan.

His thinking on programming is pretty straightforward: You don’t just add everything together. Rather, you look through all the exercises you might do and pick the ones with the most cross-over benefit relevant to your goals, and then build an exercise program out of those (and you sequence them correctly to maximize your gains in terms of strength, mobility, flexibility, skills acquisition, speed, power, hypertrophy, etc.).

I’m going to spend some time (and some blog posts here) thinking over just how I want to do that.

Just finished The Assistant by @cheribaker (@Cheri on micro.blog). Right notes for a spy novel; industrial espionage angle is a fun twist. Also, I’m a sucker for stories about people learning things.

Deep Work: Rules for Focused Success in a Distracted World by Cal Newport.

At some level, I’ve always understood deep work—the sort of work where you sit down and focus on your task for 20 or 60 or 90 minutes, long enough finish a difficult task, or make real headway on a big project.

Even when I was quite young I’d use it to get large amounts done on some big project I’d made for myself. Deep work let me create codes and ciphers for securely communicating with Richard Molenaar. It let me create maps of the wooded areas in our neighborhood where we’d play, and then assign fantasy or science-fictional elements to them. Once it let me write quite a bit of scripture for an imaginary religion. Deep work let me create maps and keys for D&D adventures I was going to be DM-ing.

I’ve never quit using deep work on my own projects. At Clarion writing a short story every week entailed a great deal of deep work. Writing an article for Wise Bread was best accomplished with an hour or so of deep work.

For other people’s work—in school, in college, and as an employee—I more often used it to enable procrastination: On any small or medium-sized project I knew I could sit down a couple of days before a task was due and crank through the whole thing in one or a few long sessions of focused work.

Given that it was such a useful capability, I’ve long thought it was kind of odd that I never really honed my capability for deep work. But through the lens of this book, I think I’m coming to understand it now.

I used to think it was because I was lazy. It was only when I quit working a regular job and started writing for Wise Bread that I came to understand that I was never particularly lazy. Rather, I just didn’t want to do stuff I didn’t want to do. Lacking that understanding I did a poor job of arranging my (work) life so that there was a lot of work I wanted to do and only a little that I didn’t want to do. Once I had work that I wanted to do, I jumped right into using deep work to get it done.

Although I take my full share of the blame for not doing a better job of maximizing the work that I wanted to do, my various former employers also deserve plenty of blame. They routinely deprived me and (most of) my coworkers the opportunity to engage in deep work.

First, they tended not to assign people a single top-priority task, but rather a set of tasks of shifting priority. (I don’t think they did it in order to be able to blame the worker when they focused on the tasks that turned out in retrospect not to be the right tasks, although that was a common result. Rather, they were just abdicating their responsibility to do their jobs as managers.)

Second, they were (especially during the last few years I was working a regular job) constantly interrupting people to ask for status updates. (One randomly timed query along the lines of “Are you going to have that bug fixed by Thursday?” which from the manager’s point of view only interrupted me for 20 seconds could easily undo 60 or even 90 minutes of stack backtrace analysis.)

At some level it was clear that the managers understood this, because there were always a few privileged engineers whose time for deep work was protected. The rest of us resorted to generating our own time for deep work by coming in early or staying late or finding a place to hide or working off-site—all strategies that worked, but not as well as just being able to close the door of our office and focus.

It wasn’t all bad management though. There were times when there was no external obstacle to doing deep work, and yet I’d not be highly productive. It’s only in retrospect that I’ve come to understand what was going on here: When I suffer from seasonal depression I find it very hard to do deep work. As a coping mechanism—as a way to keep my job when I couldn’t do the deep work they’d hired me to do—I started seeking out shallow work that I could manage to be productive on.

It’s from that perspective that I found Deep Work even more interesting than the book that lead me to Cal Newport’s work, his more recent Digital Minimalism (that I talked about briefly in my recent post on social media).

The first part of the book is about what deep work is and makes the case that it’s valuable—things that, as I said, I understood. The rest of the book is largely devoted to teaching you how to arrange your life to maximize your opportunities for bringing deep work to bear on the work you want to get done. That part, in bits and pieces, helped me understand myself in a way that I really hadn’t before.

Deep work is the way to get a big or difficult task done, but everybody has some small or easy tasks that also need to get done, so there is plenty of opportunity to make effective use of shallow work as well. Newport lays out the distinction well and provides some clear guidelines as to when and how to use shallow work to do those things where it makes sense, and in a way that protects time for deep work. He also talks about the appeal of shallow work—it’s quick, it’s easy, it’s “productive” in the sense that a large number of micro-tasks can be quickly ticked off the list.

It’s been very good for me to be reminded of all these things, because it’s easy to fall out of the habit of using deep work to do big or difficult things. The sort of rapid-fire “productivity” of shallow work has its own seductive appeal, especially in the moment. It’s only after a week or a month of shallow work, when I look back and realize that I haven’t really gotten anything done, that I tend to remember the distinction—and then pointlessly feel bad that I haven’t made any progress on the big things I want to get done.

Deep Work by Cal Newport is a great book for anyone who wants to do big or difficult things. (Also for people who manage such workers, although I don’t expect they’ll want to hear the message.)

I just finished Ultralearning: Master Hard Skills, Outsmart the Competition, and Accelerate Your Career by Scott H. Young.

It’s a good book. I think it would be particularly interesting to my brother, who of course won’t read it because he imagines that its implicit pedagogical underpinnings would not accord with his own. In fact, to the extent that I understand either one, I think it accords almost perfectly. (In particular, that learning is an activity of the learner.)

Even if he were to spend five minutes looking at the table of contents, he’d still be inclined to reject the book, because three of the nine principles are about drilling, testing, and memory retention. Since he won’t read past that he’ll never see the nuanced discussion on these topics.

What kinds of things should you invest the time in to remember in the first place? Retrieval may take less time than review to get the same learning impact, but not learning something is faster still . . . .

One way to answer this question is simply to do direct practice. Directness sidesteps this question by forcing you to retrieve the things that come up often in the course of using the skill. If you’re learning a language and need to recall a word, you’ll practice it. If you never need a word, you won’t memorize it. . . . Things that are rarely used or that are easier to look up than to memorize won’t be retrieved.

Young, Scott H. Ultralearning, pp. 127–128.

Still, it’s an excellent book for anyone who is interested in undertaking any sort of learning project. There are good, practical tips how to start such a project (how to decide what to learn, how to decide how to learn it and find resources, how to manage the project once you get going).

The book works especially to normalize the behavior of undertaking a learning project that might be considered extreme in terms of its size, scope or speed.

Ultralearning: Master Hard Skills, Outsmart the Competition, and Accelerate Your Career by Scott H. Young. Highly recommended.

Does money come with new-agey energy flows or emotions attached? For most of my life, I’d have said no (or more likely just rolled my eyes at the question). As you might expect from an economics major, I bought into a free-market model of how money worked.

Experiences over the course of my career, gradually convinced me that those ideas were . . . Well, not wrong exactly, but incomplete. I came to understand that money isn’t the kind of neutral object that it is in economic theory.

Ken Honda’s new book will let you skip over the 25 years of first-hand experience it took me to figure this out.

If you think money is a neutral, transactional artifact, then it just makes sense to earn as much as you can in the easiest ways possible. Because I was a software engineer whose career started in the early 1980s, it was pretty easy to find a job that paid well, and salaries grew rapidly, so I was doing just fine as an employee. There are certain things that come along with being an employee, the main one being that you’re supposed to do what your boss tells you to do.

I was okay with that. More okay than a lot of my coworkers, who objected when the boss wanted them to do something stupid or pointless.

My own attitude was always, “Yes, attending this pointless training class is a waste of time that I could be spending making our products better. But it’s easier than doing my regular work, and if my boss is willing to pay me a software engineer’s salary to do something easier than write software, I’m fine with that.”

The idea that I was fine with that turned out to be wrong. In fact, putting time and effort into doing the wrong thing is a soul-destroying activity. Getting paid a bunch of money for it doesn’t help. That money is, in Ken Honda’s terms, Unhappy Money.

Money that flows into (or out of) your life in a positive way is Happy Money—money that you receive (or give) as a gift, money that you earn by doing something useful (or spend to get something that you want or need). Unhappy Money is money lost or gained by theft or deceit, paid grudgingly by someone who feels cheated or taken advantage of—or, as in my own case, paid willingly, but paid to someone who doesn’t think what he’s doing to earn it is worth doing.

Honda’s thesis is that if you adjust your life around this idea—so that your own money flows are all Happy Money (and that you refrain from receiving or spending Unhappy Money)—your life will improve. My experience is that this is true.

If that insight is the key to the book, probably next most important is understanding that “There’s no peace to be found in always wanting more,” which is one of the points I tried to make when I was writing for Wise Bread.

To be honest, probably one reason I like the book so much is that a lot of the practical advice sounds a lot like what I talked about for years at Wise Bread. (For example that the strategy of just saving more quickly reaches limits in terms of its utility for making your family more secure.)

Much of the book is on the details of how to shift all aspects of your financial life toward Happy Money. There’s a long discourse on what he calls your “money blueprint”: The attitudes and practices passed down from parent to child (or rejections of those attitudes and practices), people’s basic personalities, and simple ignorance about how money works. A crappy money blueprint will predictably lead to people into cycles of Unhappy Money flows.

I’ve been interested in money for a long time, at least since sixth grade. Between studying economics in college, and embarking on an enduring interest in investing, I’m sure I’ve read hundreds of books on money. Among them, Happy Money: The Japanese Art of Making Peace with Your Money stands out.

My brother shared this comic with me a while back. I think it captures something—something about CrossFit, but also about how people react to anyone who’s “really into” anything. I’m not a crossfitter, but my expanding interests in fitness and movement have produced similarly horrified reactions to the prospect of having to engage with me on the topic—less frantic only because people are not literally trapped in an elevator with me.

I’m not a crossfitter, but my expanding interests in fitness and movement have produced similarly horrified reactions to the prospect of having to engage with me on the topic—less frantic only because people are not literally trapped in an elevator with me.

I bring this up because the recent book Lift, by Daniel Kunitz, can be read as a love song to CrossFit (although he has done a pretty good job of discreetly tucking away most of the CrossFit stuff near the end of the book).

The book is more than just one thing, and even more than a love song to CrossFit it’s a fascinating cultural history of fitness.

Kunitz uses the term New Frontier Fitness to refer to the whole emerging cluster of practices centered around the idea of “functional” fitness: CrossFit, MovNat, Parkour, AcroYoga, obstacle course racing, and any number of gymnastic and calisthenic exercise practices. Kunitz doesn’t mention Katy Bowman’s work, but it obviously fits in as well.

A key thesis of the book is that the motivating genius of New Frontier Fitness is not without precedent: It springs directly from ancient Greek ideals of fitness, and he references both ancient Greek representations of a fit body (such as the Doryphoros sculpture) and statements by ancient Greeks not unlike Georges Hébert’s admonition “Be strong to be useful.”

A key thesis of the book is that the motivating genius of New Frontier Fitness is not without precedent: It springs directly from ancient Greek ideals of fitness, and he references both ancient Greek representations of a fit body (such as the Doryphoros sculpture) and statements by ancient Greeks not unlike Georges Hébert’s admonition “Be strong to be useful.”

This cluster of ideas—in particular that fitness was a moral and social obligation, but also that functional fitness produces a beautiful body as a side-effect (rather than as a goal)—largely disappeared after the Greeks, except in tiny subcultures such as the military. It has only reemerged in the past few years as the various things that Kunitz refers to as New Frontier Fitness.

In between—and the 2000-year history of this makes up of the center of Kunitz’s book—there were many things that were not this particular tradition of functional fitness, but instead were aimed at producing a particular type of body (body-building, aerobics, etc.)

It’s impossible for me to talk about Daniel Kunitz’s Lift without comparing it to another book—Christopher McDougall’s Natural Born Heroes. They are similar in at least two ways. First, they both compare modern fitness culture to that of the ancient Greeks. Second, they both appear to have been written just for me.

It’s impossible for me to talk about Daniel Kunitz’s Lift without comparing it to another book—Christopher McDougall’s Natural Born Heroes. They are similar in at least two ways. First, they both compare modern fitness culture to that of the ancient Greeks. Second, they both appear to have been written just for me.

A third book that I read recently but haven’t written about is Spark, by John J. Ratey, which overlaps in the sense that all talk about intensity as a key aspect of exercise to produce functional fitness. (If all you’re interested in is appearance and body composition, you can get most of the way there with a diligent application of low-intensity exercise, but some amount of intensity is highly beneficial for functionality and brain health.)

All three books are worth reading.

Image credits: CrossFit Elevator comic by Ryan Kramer from ToonHole. Doryphoros photo by Ricardo André Frantz.

I’m not sure exactly when I discovered parkour. Its first mention here in my blog is in May 2014 when I talk about starting to practice precisions and shoulder rolls.

I’m not sure exactly when I discovered parkour. Its first mention here in my blog is in May 2014 when I talk about starting to practice precisions and shoulder rolls.

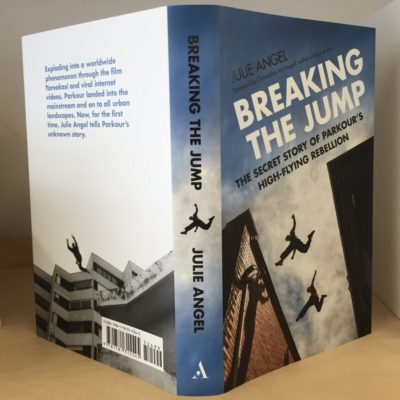

By then, Julie Angel had already finished a PhD and created a large body of photos and videos on parkour.

I came across her work fairly early, and immediately appreciated its strength, so I was delighted to learn that she was writing a book. I bought a copy as soon as it came out, and spent last week reading it.

I’d read some about the early history of parkour, so I knew about David Belle as an individual and the Yamakasi as a group, but this was largely my first exposure to the other early practitioners as individuals—and a bunch of interesting individuals they are.

Early in the book Angel takes a stab at tweezing out the many threads that went into making parkour something that appeared in this place at this time: The urban planning that produced the built infrastructure in Lisses and that also drew in the immigrant population that lived there. The life- and family- histories of the handful of young men who became the Yamakasi. The kinds of men they were. Angel never really pins down exactly why these young men produced parkour when no one else had done so, but it’s a credible effort at answering a question that’s probably unanswerable.

Because on the one hand, many other groups of young men could have created parkour. Most of the key traits of these young men—a certain facility with movement; a willingness to train very, very hard; a tendency to push one another to ever greater efforts (and to let themselves be pushed)—are not that rare. Although many young men are clumsy or lazy, you need only look among the national-level competitors in any boys or junior individual sport, or even at any good high school sports team, to find both movement skill and the capacity for hard training.

More important than those things—which are, as I say, fairly common among young men—was an ethos that leaned against that willingness to push and be pushed. It’s an ethos exemplified in some of their sayings—things like “Start together, finish together,” and “Be strong to be useful.” Everyone was pushed outside their comfort zone, but no one was pushed to attempt anything that he didn’t know he could succeed at. It is surely the reason that early parkour practitioners had such an incredibly low rate of training injuries whether from accidents or from overtraining. (Would that runners were as durable.)

New to me—and a perfect example of that ethos—is the picture Julie Angel gradually paints of Williams Belle. Younger than the others, he was someone I hadn’t even been aware of until I read the book. Williams is portrayed as having all the movement skill and all the willingness to train very, very hard as any of the other pioneers, but lacking the ego of David Belle, and possessing teaching methods that seem uniquely gentle.

She has Stéphane Vigroux saying this about Williams:

On the surface it was the same training school, but somehow the energy and feel when observing Williams was different. . . . From the first jump . . . Williams had known that the discipline should be about helping and sharing with others.

It makes Williams sound like someone I’d like to get to know.

Angel includes a good look at the prehistory of parkour—Georges Hébert and others—and a look at contemporaries who created things that overlap—people like Erwan Le Corre—but it’s not really about them. Most of the book is about the early practitioners. But only most of the book. A little bit—maybe ten or fifteen percent—is kind of a memoir of Julie Angel’s own experiences beginning with parkour. Her stories of her struggles to break her own jumps, learn to balance on a rail, or simply to attend her first class are very effective at illuminating the journey of the founders.

Maybe she used every such story she had—at least, that’s the only good reason I can think of for including so few, because frankly, those bits are some of the best bits in the book. If she wrote a longer memoir of her own journey learning parkour, I’d buy it.

If you’re interested in the history of parkour, and especially if you’re interested in understanding what it meant to those early folks—what it meant to work together, to train very hard, to confront their fears and overcome them together—this is an outstanding book

Breaking the Jump: The secret story of parkour’s high-flying rebellion by Julie Angel.

I no longer remember the precise path through which I came to Katy Bowman’s work, but it must have gone something like this: Parkour to Georges Hébert to Erwan Le Corre to Katy Bowman.

I no longer remember the precise path through which I came to Katy Bowman’s work, but it must have gone something like this: Parkour to Georges Hébert to Erwan Le Corre to Katy Bowman.

Once I found her Katy Says blog, I stuck around for a while—binge-reading the trove of posts I found there, watching the related videos, and listening to back episodes of her podcast. That material, together with what I found in her then-newest book Move Your DNA, went into a piece I wrote for Wise Bread that suggested natural movement as a way to get fit that was doubly frugal—no cost for the gym, plus you get to do some of your exercise while you’re working.

Unbeknownst to me, Katy was on the verge of publishing a book on just that topic and when I shared my article with her, she offered to send me a review copy of Don’t Just Sit There.

Katy’s thesis in brief is that your body responds to the forces applied to it by adapting itself: moving toward the most optimal form for dealing with those forces. The forces it experiences are wildly diverse—gravity, the continually changing pressures caused by clothing and by breathing, the stretching and compressing of all parts of your body as you move them, the activity of your intestinal biome, etc. Your body as it is now includes a lifetime of accumulated adaptations.

If you had spent your life moving as humans moved during the period in which the human form evolved, your body would have adapted itself most excellently. But you probably haven’t. You’ve probably spent your life sitting in chairs, wearing shoes, riding in cars, and doing a hundred other things that no one had ever done until just the last few hundred years—things that have produced a relatively novel set of forces, resulting in a set of adaptations that are probably not ideal.

Among those adaptations are many things that are considered diseases—osteoarthritis and osteoporosis being two of the ones most obviously related to the history of forces applied to your body. But most “lifestyle” diseases like high blood pressure, coronary artery disease, type-2 diabetes, allergies, and asthma also have their roots in adaptations to the lifetime history of forces applied your body.

It is these adaptations—and the resulting disease processes—that explain why sitting all day is an independent risk factor for all-cause mortality, even for people who exercise regularly.

And that is the starting point Katy has chosen for this book. Sitting all day is clearly bad for you, but what should one do instead? Using the model that Katy provides, it is easy to understand that simply replacing sitting all day with standing all day is not an improvement. The problem is not any particular posture; it is maintaining a static posture for hours each day. Specifically, it’s the forces produced by maintaining a static posture for hours each day.

What’s good about this insight—that many disease processes are deeply related to your body’s response to the forces applied to it—is that it is very easy to apply different forces, and thereby produce different adaptations: Adaptations that make your body stronger, more functional, and more healthy. These different forces can be produced by engaging in natural movement.

It is, of course, no easy thing to overcome the results of a lifetime’s movement history. You probably can’t even think of many of the things that all humans did daily for millennia, and without a lifetime of practice, you wouldn’t be able to do them well. If you tried, you’d surely hurt yourself—your adaptations have produced a body that can no longer do certain things.

Happily, Katy’s book provides exactly what you need: a program for safely achieving the capability of filling your day with natural movement—without hurting yourself, and without hurting your productivity. (I was going to say “and without losing your job,” but it’s more than that. Katy is endlessly productive, and clearly cares deeply about your ability to be productive as well, whether you have a job or are simply doing work you think is important.)

This provides the core of the book. There’s a chapter on how to stand (because your lifetime movement history has probably produced habits—and a body—that don’t make it automatic to stand in proper alignment). There’s a chapter on how to sit (for the same reason, plus you probably have a chair that encourages poor posture). There’s a chapter on the small movements that don’t even need to interrupt your work. There’s a chapter on the larger movements that probably do interrupt your work, but only for a minute or two.

All that is preceded by a chapter on building a workspace that doesn’t lock you into one or a few static postures, and then followed by a short group of chapters that use all the preceding information to build a specific program with exercises that build toward filling your workday with natural movement.

What I like best about the book is that it constructs a model for how to think about all these issues. Instead of finishing the book wishing that you could ask the author the right way to deal with this or that particular workplace situation, you can figure it out on your own by applying the principles presented.

If the book has a flaw, it is only that some of its recommendations are based on specific research, while others are simply Katy’s well-informed gut-instinct about what would be better—and the distinction is not always well-marked. For example, there’s an excellent reference to research on the health effects of light pollution to justify suggestions for dealing with lighting and screen time. The related suggestions for engaging in “distance eye-gazing”—that one take “a quick glance every five minutes, and more extended gazes every 30 minutes”—don’t include a reference. I suspect this is because there has not yet been any research to quantify whether those specific time periods are frequent enough and long enough to significantly improve outcomes, but the book doesn’t say.

If you do work—whether for a living, or simply because you’re trying to accomplish something—this is a great book. It’s filled with actionable tips for adapting your workspace to allow you to fill your time with natural movement, and it provides a program for doing so. Most important, it constructs a model for understanding the underlying problem, meaning that you can adapt the program to your own situation.

The paper book is the text portion of a multi-media program with audio and video as well as an ebook. I haven’t seen it, but having heard and seen audio and video created by Katy, I don’t doubt that it is also excellent.

You can buy the paper book Don’t Just Sit There by Katy Bowman from Amazon. (That’s an Amazon affiliate link.) Or you can buy either the paper book or the multimedia program directly from the publisher.

As a bonus, here’s video of Katy filling an hour of work with exercise and natural movement, run at high speed so you can watch the whole hour in just a couple of minutes.