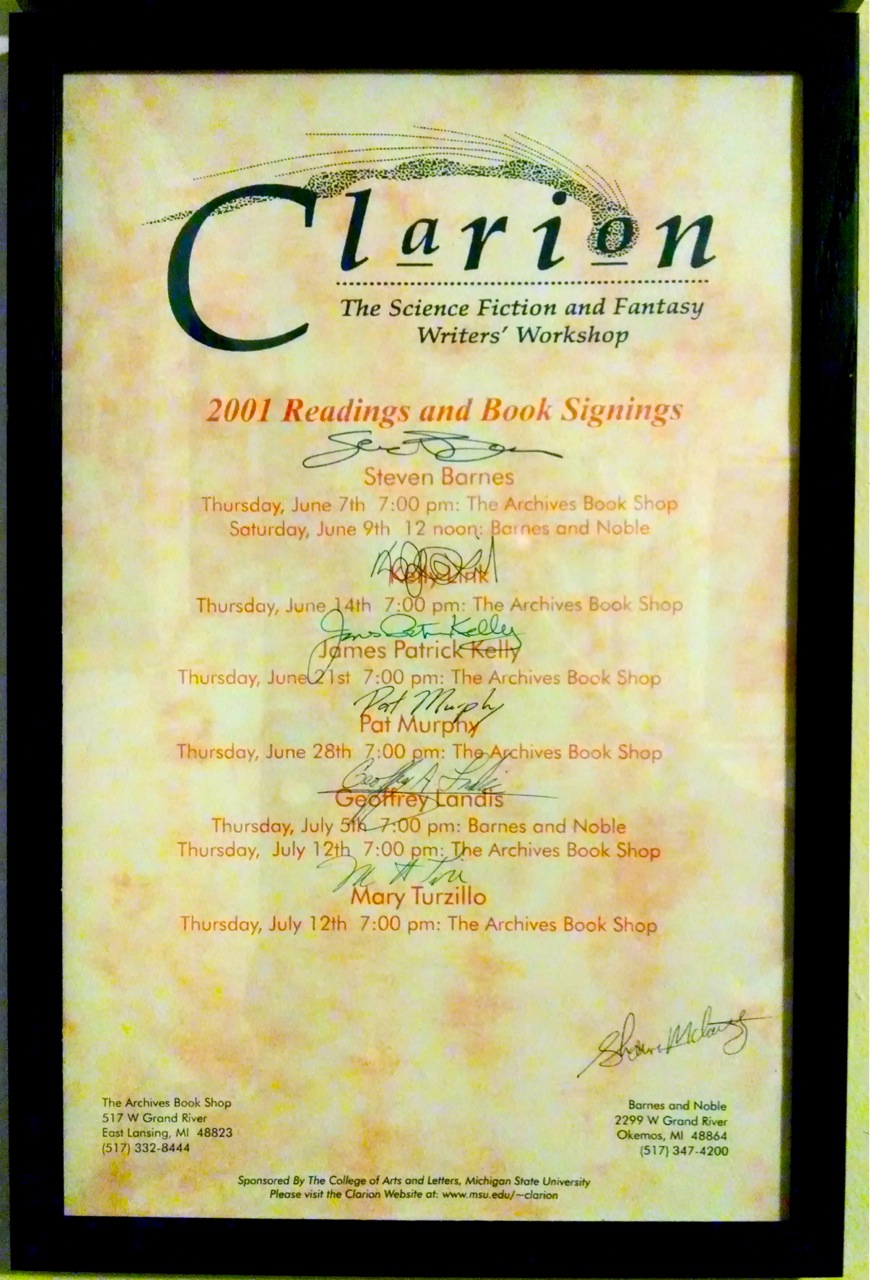

When I attended Clarion in 2001, Steven Barnes was my week-one instructor. Of course the class was about writing, but Steve talked quite a bit about martial arts in general and Tai Chi in particular—things that were important in his own life and in his own writing.

Although I had been interested in Tai Chi even before that, I didn’t get it together to find a class until 2009. But I managed to find a great class; one that made room for my idiosyncratic movement issues. It quickly became a daily practice that continues to this day. For several years I taught Tai Chi. I’ve retired from teaching it, but I still attend a group practice session in a nearby park several times a week in nice weather. (It’s free. Anyone is welcome. Send me email if you’re local or visiting and are interested in attending.)

All of which is to say that I was very pleased to find that Steven Barnes was teaching three Tai Chi classes at this year’s WorldCon.

Teaching individual Tai Chi classes is a fundamentally peculiar thing. I mean, if you’re trying to learn a Tai Chi form, you can expect to spend a year at it, if you take two or three classes a week. In that context, it’s kind of hard to know what to do with a single class, and the issue actually gets even more fraught if you’re teaching three classes, rather than just one.

Steve threaded the needle by focusing a large part of each class on talking about living well.

I started this post wanting to talk about all the great stuff that Steve covered—about movement and about life. But I hadn’t taken notes, and became somewhat daunted knowing that I’d skip all sorts of important bits. But, given the choice between documenting a few of the bits that stuck with me and documenting nothing, I’ve decided to go with the former.

I would like to emphasize that all these things are colored by my own thinking, so it is virtually certain that Steven Barnes would look at several of these things and go, “Wait a minute! That’s not what I said!” Don’t blame Steve for anything I get wrong. But this is how I remember it:

Purpose of life

On the first day, Steve mentioned that the Dali Lama said the purpose of life was to seek joy and to be of service. Steve used that statement to go on a short rant about being of service—how it’s the real motivation that gets most people out of bed in the morning. “Even if it’s just to feed the cat.” But on the third day he told a story that added some context.

Originally, he said, the Dali Lama said that the purpose of life was to seek joy. But people criticized him, saying that it sounded selfish to say that was the purpose of life. And the Dali Lama pushed back saying, “But as soon as you find joy, you’ll want to share it, and immediately find yourself drawn to be of service.” But people continued to complain, and eventually the Dali Lama conceded to the complaints and added the “and be of service” part.

And I think it’s good to tell the story this way, so that you get the context that “being of service” is an automatic urge, as soon as you find joy. It has certainly been my own experience.

Expertise

People almost always reach a point while learning something, where they perceive themselves as no longer getting better at that thing, even as they continue to train. Different people will keep training for different amounts of time before giving up, but most people eventually give up, before becoming an expert.

That has certainly been my own experience. There must be a hundred things—playing chess, identifying birds, gardening, StarCraft—where I did it enough to get pretty good at it, then found that getting significantly better would be hard work, and didn’t make the effort.

Steve suggested that 100 hours of study or training will give you a passing familiarity with some topic or activity, and 1000 hours gets you good enough to participate in a conversation about some topic with an expert. He also made a passing reference to the 10,000 hours of deliberate practice that it takes to develop actual expertise in something, but mentioned in an almost off-hand way the same issues with that idea that I talk about in my post on practice.

Three areas of life

One thing that I remember Steve talking about at Clarion was that he evaluated people as possible models for himself based on whether or not they were succeeding in each of three specific areas:

- Financial success: Does the person have some sort of career or business that supports them and could support a family at whatever standard of living that person aspires to?

- Family success: Has the person put together and maintained the sort of family they desire?

- Physical success: Is the person fit enough and skilled enough to be able to do the things they want to do?

Steve specifically evaluates people on these standards when they offer unsolicited advice. If the person trying to tell him what or how to do or be has all three of these areas under control, then maybe their advice is worth listening to. Otherwise, probably not. (I gather he has a different standard for when he’s the one seeking advice or a service. He probably wouldn’t refuse dental care from a twice-divorced dentist or to fly on a plane just because the pilot was out of shape.)

Pain

When I taught Tai Chi I would begin the first class of each session by telling students that nothing we did in class should hurt. If anything hurt, they should make the move smaller, do a different move, and just wait until we went on to the next move.

Steve had a different perspective. He told students that any pain they felt while training should never go above a level of 3 (on a scale to 10).

I pondered that quite a bit since then, and I think Steve’s perspective makes sense in a way, especially for students who have chronic pain. I never meant to tell my students that they couldn’t take my class if they had pain; just that they shouldn’t do any move that made their pain worse. Another population for whom Steve’s standard probably makes sense is serious athletes or serious martial artists.

Movement

We probably spent half of each class moving, starting with a very nice mobility warm-up. It’s rather a lot like what I’ve taken to calling my morning exercises, but focused on working all your joints through their full range of motion, leaving out the muscle-activation stuff that I’ve added for my own purposes.

The form

Steven taught us the first three moves of his Tai Chi form. The first move was roughly the same as the move called Preparation in the form I do, but Steve emphasized the breathing as the entry point into the move: You inhale, and the movement raises your arms (leading from the tops of the wrists), and then you exhale and your arms fall (leading from the bottoms of the wrists). The second move involved stepping forward, turning your foot, and then pressing forward with your hands facing one another (a move we call “ji” in our style). I’ve already forgotten the third move.

Martial art versus martial science

Steve made a distinction between martial art and martial science. Martial science is figuring out the best way to win a fight or battle. Martial art, like any art, is about expressing yourself, in this case through fighting or battle.

This is something I’ve just come to understand very recently—that the “best” or “most effective” martial art is very context dependent. If you’re going to be fighting a duel—hand-to-hand, with swords, with pistols, whatever—that’s very different from battlefield fighting, where you would find yourself with potentially any number of opponents, along with some number of compatriots.

As an aside, my own observation: Krav maga is an excellent choice of martial art, especially if you have a handful of opponents. It has downsides, especially if you have “opponents” who are not enemies. If your opponents are people that you wouldn’t be comfortable maiming or killing, Brazilian jiu jitsu would be a better choice, but perhaps not if you find yourself surrounded by four or five gang members on the street after dark.

The point Steve was making is that martial arts are only appropriate in the appropriate context. There are many circumstances where “fighting,” and “winning a fight” yields significant benefits, but they’re context dependent. He mentioned an important teacher he had who, upon being asked for instruction regarding the best move for some circumstance, said “You’re a primate. Use a tool.”

Being willing to die

Steve told a story about being bullied in school, about how when he was bullied to the point where he couldn’t take it any more, he crossed to the middle of the nearby busy street. Standing on the yellow line, with traffic zipping past in both directions, he dared the bully to come out there and fight him.

The bully realized that he’d made a mistake.

The line, as I recall it was, “You have to be ready to die, and ready to take him with you.” I think a whole lot of martial culture involves people who have reached that point.

Fighting to stay alive

One thing that got some pushback from one member of the class was the idea that anybody would fight to live: Even someone so depressed as to be suicidal, if you put their head in a bucket of water, would fight to survive. One member of the audience suggested that clinical depression was a matter of brain chemistry, which Steve did not dispute. But the student talking about it said that, when she was at her lowest, if you’d killed her she’d have thought you were doing her a favor. Steve suggested that, even if you’d think that way in the abstract, if you find your head thrust into a bucket of water, you’d do everything you could to to breath.

I have no doubt that Steve was right here. A person suffering from clinical depression might well wonder why they’d fought to hard to survive, but I very much doubt that they’d just breath in water and be glad to pass on, even if they were at the point where they might later that day have chosen to swim into the sea too far to be able to swim back.

Okay.

Those are the bits I remember from Steve’s three Tai Chi classes. There was a lot more—probably other things that were more important than these.

I find myself a little surprised that the “three areas of life” stuff stuck with me the way they did. At Clarion I was doing pretty well in two of them—I had a career in software engineering that provided for my family, and I was in a successful long-term relationship with my wife. But my physicality wasn’t yet on point: I was somewhat fit; I could walk a long ways, I could even run a couple of miles, but I was overweight and unhappy about it.

I’m surprisingly pleased that I’ve managed to get all three under control. That same career lasted long enough (and I boosted my income enough with writing and teaching Tai Chi), that I’m able to support myself on my pension and my investments. I’m still married to the same woman I was married to when I went to Clarion. And since I was in Clarion I lost around fifty pounds while at the same time developing the ability to move in ways that would have been impossible when I was younger.

My Tai Chi practice was important to all those things. Perhaps it seems even more important than it was, because it was my entryway into moving better. Since stepping through that door I’ve explored a wide range of natural-movement practices. During the pandemic I (to an extent) switched back to an exercise- (versus movement-) based paradigm, but really just because exercise suited the circumstances. As the pandemic winds down, I expect I’ll switch back to movement rather than exercise as the focus of what I do.

Looking for a Steven Barnes link to use here I found this post in which he talks about the very classes I was in:

I was very pleased to be able to take another class—three classes!—from Steven Barnes. I enjoyed them, and I learned a lot.