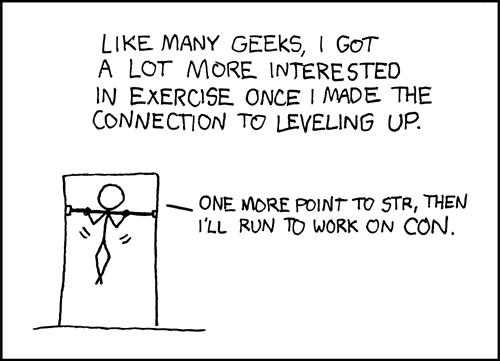

I have long had mixed feelings about gameification, where you use the structures that underlie games (like points, achievements, badges, etc.) to motivate yourself to do the things you already know you want to do. I’m dubious about it, but at the same time, I do find myself motivated by such structures, which makes it very tempting to use them. (For exercise in particular, but really everything.)

Just lately, I’ve started thinking about a modest alternative: storyfication, where you use the structures of fiction to motivate yourself to do whatever it is you want to do.

Essentially, you tell yourself a story about what you’re doing, rather than making a game out of it.

Plenty of people do related things. There are several popular YouTube fitness channels that are all about using anime stories and situations, or superhero stories and situations, as inspiration for working out. (See for example JaxBlade, The Bioneer, or Kevin Zhang.) Some of them are primarily about aiming for the aesthetics of anime characters, but some reach into the story lines of specific anime. And some—the most interesting ones—use the underlying structure of anime or comic-book type stories as workout inspiration.

I’ll rough up an example here. Any story structure might be worth trying, but I’m inclined to start with the Hero’s Journey story structure. I’m assuming that we’re talking about doing exercises to get fit, but the basic storyfication thing could work for anything where you need to engage in repeated actions to get better at something—learning to paint, say, or learning to play the violin.

You begin with the Call to Adventure. If we’re talking about exercise, it would be a desire to get fit. Of course, the hero always initially resists the call. (Getting fit is a lot of work that’s hard and sometimes uncomfortable.) But finally the hero (you) chooses to accept the call.

The bulk of what you’d be doing would be “traveling on the road of trials, gathering powers and allies.” (That is, consistently doing your workouts.)

Dividing things up into separate books or seasons makes good sense. It can be very useful to grind away on one or a few things (building strength, say, or building endurance, or explosiveness) for a few weeks or a few months, but you need to include occasional breaks. You might consider each week of workouts a chapter or an episode. Put six or eight or ten together, then take a break. And then, of course, return for the next volume or the next season, perhaps with a new focus.

In the Hero’s Journey structure, the next thing would be to confront evil and be defeated, leading to a dark night of the soul. I don’t see much value in writing this into your plan, but there may be value in keeping the idea in your pocket for when things go awry. And, of course, things will go awry. A major project at work or at home may take so much time you can’t fit in all your workouts. An injury or illness may derail your workouts for a time. Maybe you’ll just hit a plateau in your fitness journey.

When something like that happens, well, you can view it as confronting evil. Remember, after being defeated, you face the dark night of the soul. One thing you might do at this point is think deeply about what obstacle might be blocking your progress. In fitness there are many possibilities: insufficient volume of exercise, insufficient intensity, insufficient recovery, poor exercise selection, poor nutrition . . . . The possibilities are nearly endless, and it is often hard to know which is the real culprit.

For that reason, the next step in the hero’s journey is especially appropriate: You take a leap of faith. Even though you can’t know what’s the best choice, you make a choice anyway. Maybe you ease up on intensity and focus on recovery. Maybe you double-down on exercise volume. Maybe you focus on your diet.

Whatever you choose, you can think of it as confronting evil again. And in a proper hero’s journey, this time are victorious.

Go ahead and write this part into your plan.

The final stage of the Hero’s Journey is that the student becomes the master. Again, there’s no need to write that into your plan. But it is entirely possible that having some success with storyfication will make you feel like sharing your insights with others, which is really what being a master of something is.

I generally view both gameifcation and storyfication as essentially neutral—neither good nor bad, except to the extent that the thing being motivated is good or bad.

Perhaps related to this is a word I’ve just learned:

“hyperstition.” The term, coined by “accelerationist” writer Nick Land, describes the belief that one can manifest future realities by telling compelling stories, and that prophecies become self-fulfilling through repetition and virality.

— https://www.thenerdreich.com/silicon-valley-apocalypse-capitalism/

Telling yourself a compelling story can definitely help you put in the time and effort to achieve your goals, just like the structures that underlie games can do the same.

Is anybody else out there interested in using story structure to motivate themselves to exercise (or do something else)? Anybody already doing so, and able to provide some first-hand experience?

Let me know! (See my Contact page for many ways to contact me.)