One metric that the Oura ring tracks is inactivity time: basically, the amount of time spent just sitting. It is here that I perhaps see the biggest dog-related change.

I have always spent a lot of time just sitting: I sit to work, I sit to read, I sit to watch TV, I sit to play a video game, I sit to write a blog post, I sit to eat. I sit in the morning while I drink my coffee, and I sit in the evening before getting ready for bed.

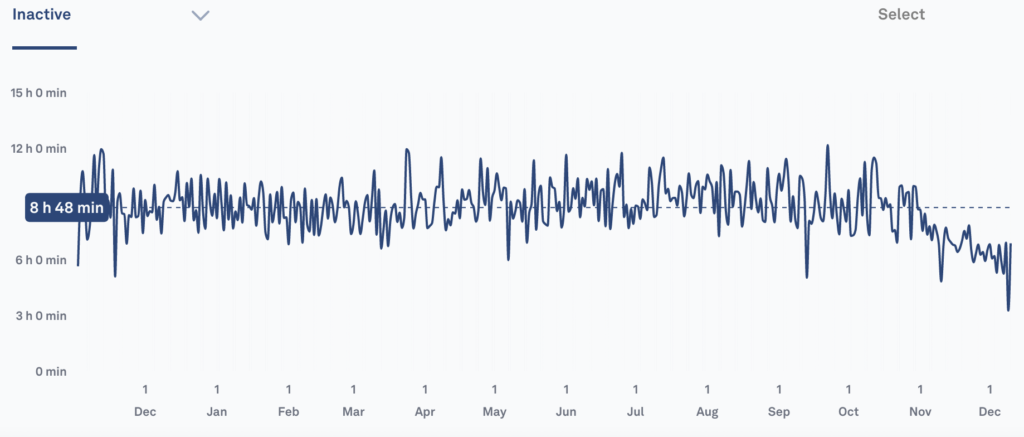

The Oura ring folks rather emphasize this particular metric, suggesting that “Keeping your daily inactive time below 8 hours works wonders for your body and mind.” I didn’t doubt this, but I did a pretty poor job of actually doing it. I had the occasional individual day when my inactivity was below 8 hours, but it was usually somewhat over. In fact, my average daily inactive time for the year before we got a dog was 9h 2min.

Since getting the dog, I’ve been way, way more active. I mentioned a few days ago that I was sleeping lot better, and listed a few metrics that had changed that seemed to be related—in particular, walking a lot more, but I hadn’t thought to check how my inactive time had changed, and the results are significant. My average daily inactive time over the 5 weeks since we got the dog has fallen to 6h 38min.

The shift is pretty obvious in a graph of my inactive time starting one year before I got the dog and continuing through yesterday:

The change was dramatic enough that just 5 weeks of post-dog data pulled the overall average down by almost 15 minutes per day. (It’s actually kind of interesting how variable the individual data points are in the first year, and yet how absolutely flat the average is, until Dog Day.)

Well, I have been sitting for rather longer than I probably should to get this post written. I’ll go ahead and post it, and then carry on with the activities of the day.