I’ve been lifting weights for decades. I was pretty consistent about it for a long time. For years while I was working at a regular job, Jackie and I would go to the Fitness Center and lift before I went to the office at least two, often three times a week, using whatever machines they had (three or four different brands/styles of machines over the years). I saw pretty good gains the first six weeks or so that I was doing this, but they leveled off. I kept at it for years after that, with very little to show for it.

All that time I imagined that the issue was intensity—to make more gains, I needed to lift more and harder. I now think that was wrong. I think the problem was just that machines are a crappy way to build strength or muscle.

Four and a half years ago we moved to Winfield Village, which has a pretty good set of free weights. I’ve been using them—once again without much to show for it. In this case, the issue is not a matter of using the wrong equipment or a lack of intensity—it’s that my consistency has fallen off. I get on a schedule of lifting two or three times a week, but only keep it up for a week or two and then miss a few workouts.

Happily, this month I’m doing pretty well. In 21 days I’ve gotten in 9 lifting sessions, which is just about exactly my target. (I aim for every other day, so when I miss an occasional day it still comes in at 3 times a week.)

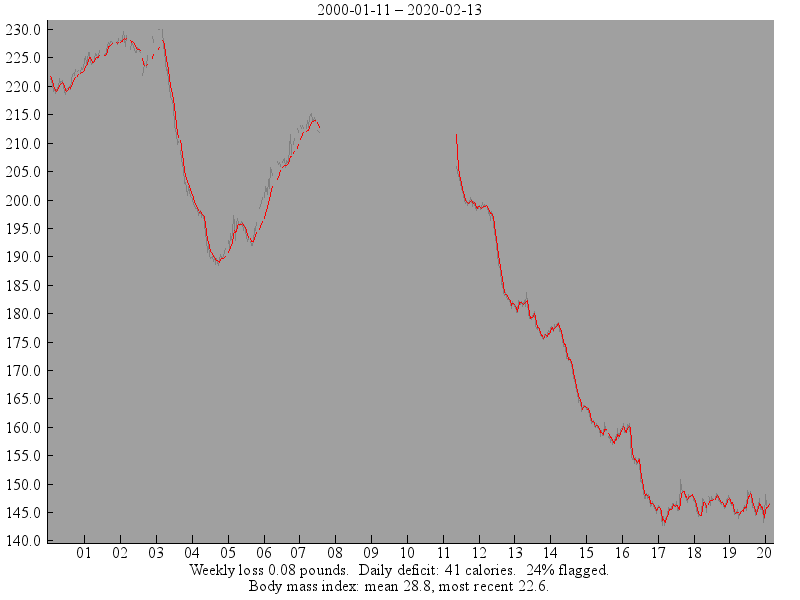

I’m seeing some nice strength gains (although after just three weeks I can’t be sure I’m not back in the situation of “anything will build strength for six weeks”). I’m also putting on some weight—probably just because I’ve been eating too many carbs, which I’ll fix here shortly, but in the meantime I’m choosing to imagine that I’m adding some muscle as well.

Understanding that consistency is the key, maybe I’ll be able to keep it up. (Watching my older relatives become frail due to sarcopenia, I’m determined to avoid that fate.)

I’m pretty sure I’ll manage okay until the weather turns and I have to start balancing the lifting with the running and hiking. (I’ve only gotten in one run this month, because of ice and cold.) We’ll have to see after that. But as I say, I’m determined.