You couldn’t see it, even if it weren’t behind the Oura ring “activity” sticker, but there’s a Great Blue Heron near the middle of this photo.

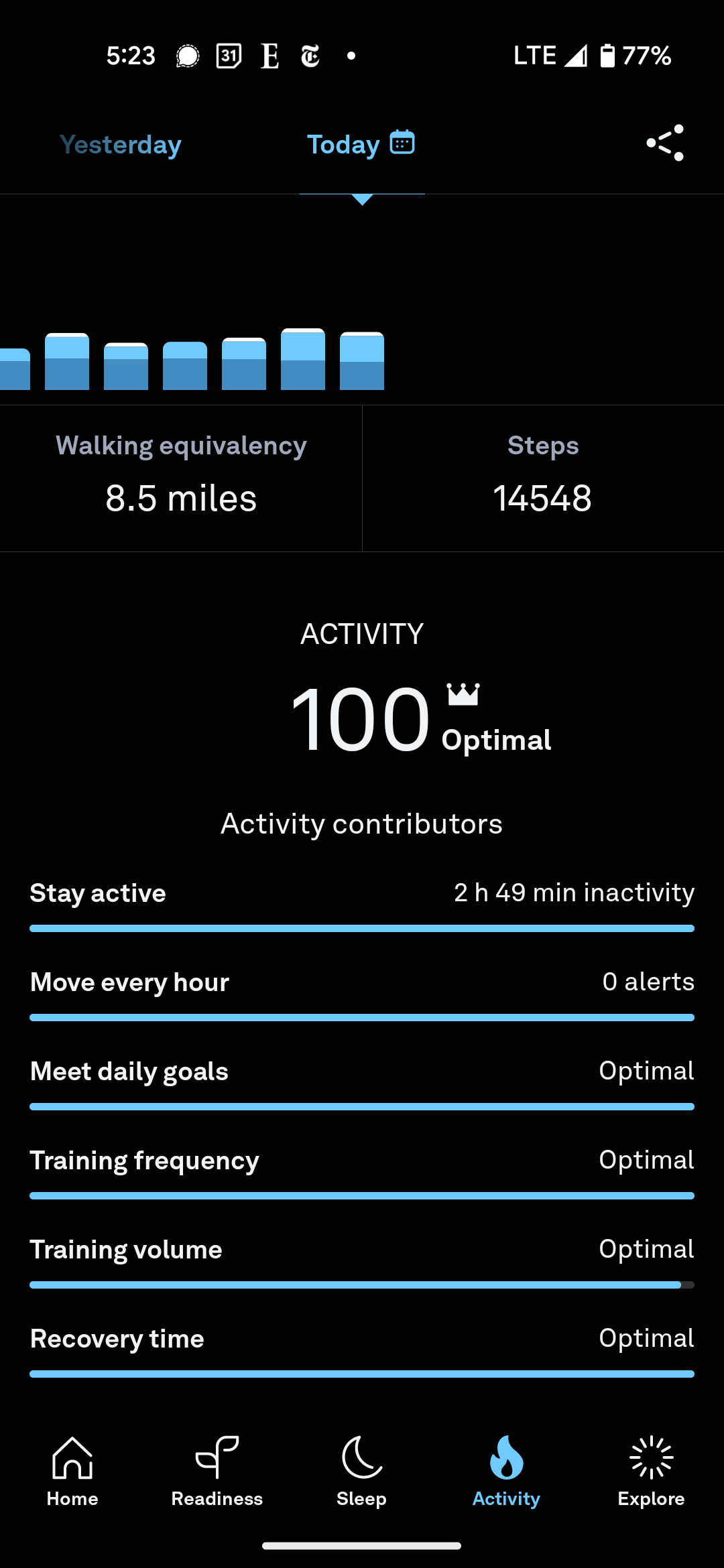

Anyway, “Go me!” for getting an activity score of 100 from my Oura ring.

You couldn’t see it, even if it weren’t behind the Oura ring “activity” sticker, but there’s a Great Blue Heron near the middle of this photo.

Anyway, “Go me!” for getting an activity score of 100 from my Oura ring.

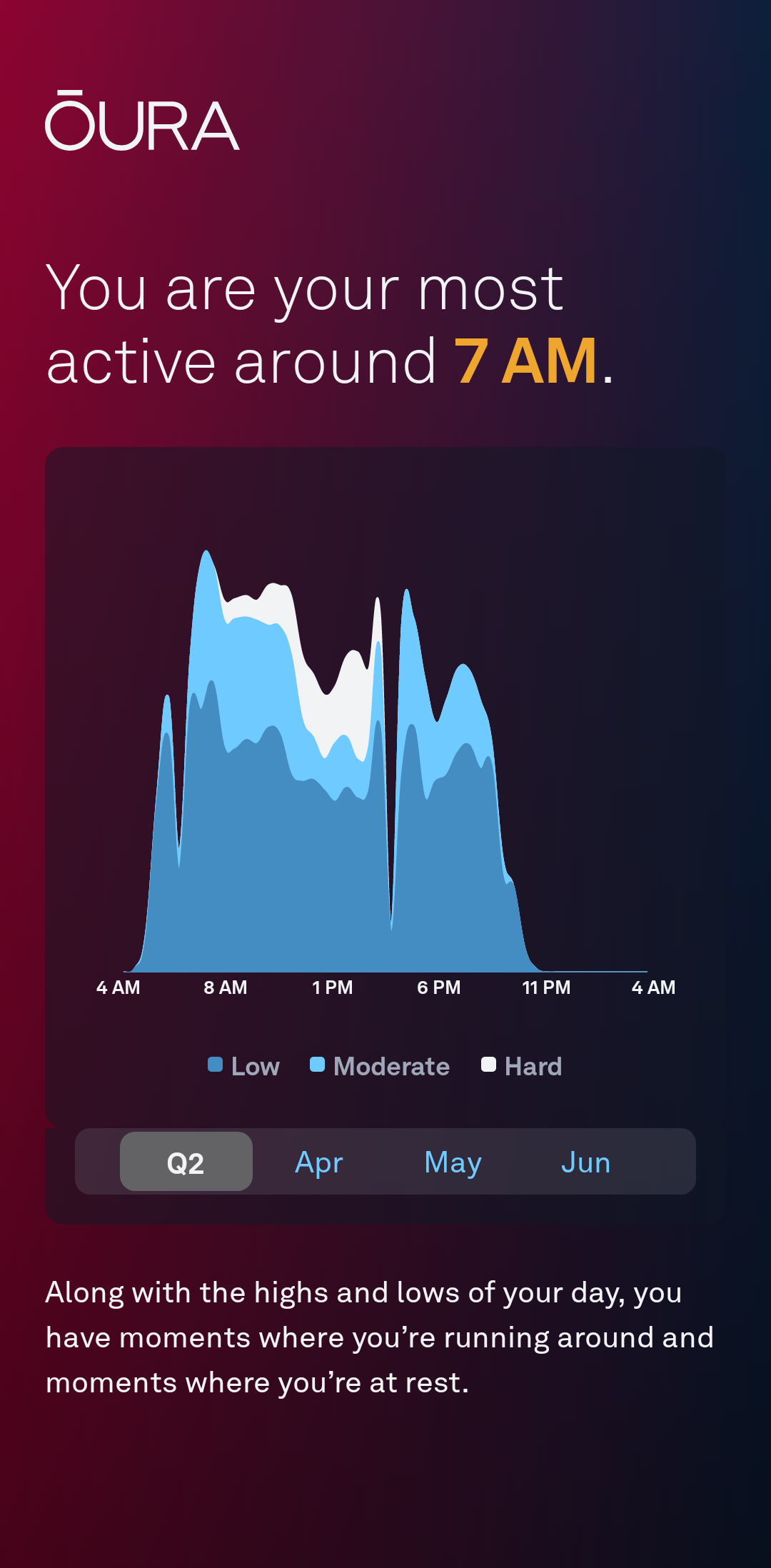

Mildly amusing. Low peak for the first dog walk, notch for drinking coffee and Jumbletime, then my most active time is 7:00 AM, for the second dog walk.

Before I got a dog, my most active time was 11:00 AM, because that’s when I finally get to my workout.

My activity score of 100 due purely to walking the dog. Well, and sleeping better since getting a dog.

I get scores in the upper 90s pretty often, but scores of 100 less so. Today I kept my “inactive time” nice and low, which I think is what made the difference.

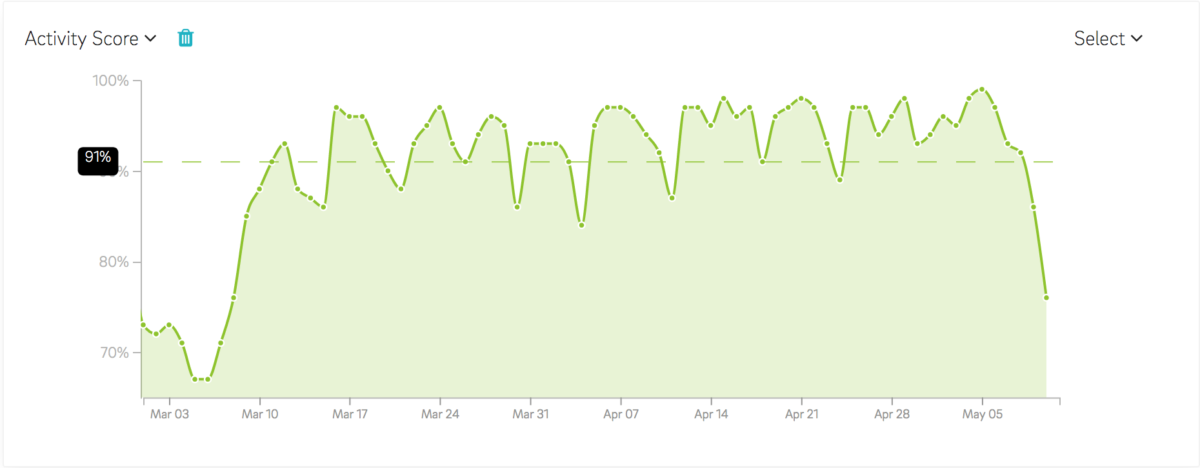

My Oura ring prepared an annual summary of the data it has gathered. One interesting bit shows the dramatic change in my activity since getting Ashley

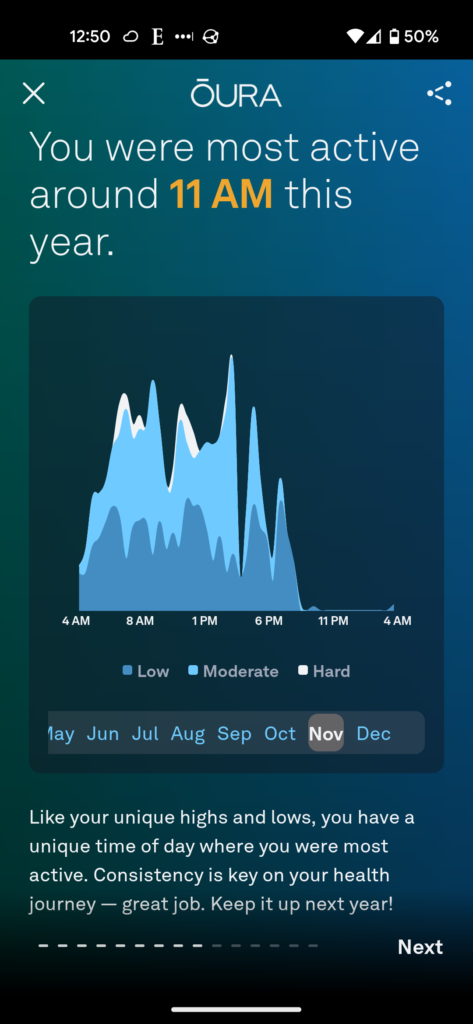

This shows my activity levels across the day, averaging the whole year together:

The white area shows when I was engaging in “hard” activity—basically running, high-intensity interval training, and (if I was really going at it) lifting weights. I did quite a bit of those things for most of the year, and the Oura ring is interested to observe that it was largely between about 10:00 AM and noon.

That graph averages the whole year together. This graph shows the same thing, but just for the month of November (we got Ashley on November 2nd):

I had only a modest amount of hard activity, mostly early in the morning and then again at mid-day. (I assume those are bits where Ashley wanted to run and I tried to keep up with her, something that I quit doing after tripping, falling, and splitting the skin across my knee.) Basically, I replaced nearly all my hard activity with lots and lots more medium activity.

Just as an aside: My 4:00 PM cocktail hour really shows up on these graphs, with modest spikes in activity that I think have gotten larger now that I get the dog out for pre- and post- cocktail hour walks.

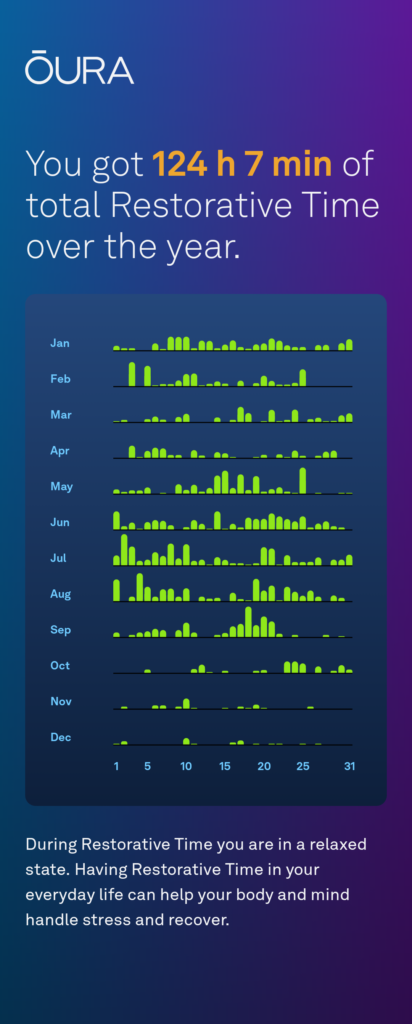

One other tidbit that changed with the dog has been my “restorative time,” periods of low activity where the heart rate falls quite a bit. You can see the difference between the first ten months of the year and the last two here:

I used to get at least some most days, but since I got the dog my restorative time has really dropped off. I think that’s partially just because my periods of low activity are shorter (because pretty soon I have to take the dog out again), and maybe also because, since I have less hard activity, I don’t feel the same impulse to really slow down when I get a chance to do so.

First, let me say that maximizing my Oura ring activity score is, in and of itself, of no value whatsoever—except to the extent that it reflects and reinforces my efforts to get an appropriate level of physical activity.

Happily, I find that getting an appropriate amount of activity generally results in a higher score. So it works at that level, with perhaps a few mismatches between what I think is appropriate and what the Oura software thinks is appropriate, the main one being their idea of what counts as a recovery day.

Periodization of training—getting a mix of training days and recovery days—is a great idea. In fact, the lack of periodization is one of the limitations with Google Fit, whose model is to have a daily activity goal which is a little aggressive—a goal that motivates you to to get out and walk just a little more than you otherwise might. The problem is that a goal that’s even a little bit aggressive is going to be excessive for your recovery days, while still being much less than you probably want for your training days.

This is where the Oura ring software is a big step up from Google Fit. It strongly encourages both training days and recovery days. Unfortunately, its idea of a recovery day seems a bit too strict for me:

For Oura, an easy day means keeping the amount of medium intensity level activity below 200 MET minutes (200-300 kcal/day), and high intensity activity below 100 MET minutes (100-150 kcal/day).

In practice this can mean doing lots of low intensity activities, getting healthy amounts of medium intensity activity (30-60 min), but only a small amount of high intensity activity (below 10 min).

Now, that’s all well and good, except that ordinary walking is a medium intensity activity, and (except when the weather is crappy) it’s a very rare day indeed that I don’t end up walking more than an hour—meaning that I basically never get a recovery day in Oura ring terms.

The result is that whenever the weather is nice my activity score starts dropping, because I’m not getting what my ring thinks is appropriate recovery. Then, when there’s a couple of days of crappy weather and I sit around the house all day, my score will climb (as my recovery time value improves). Then, as soon as the weather gets nice again and I can get out and be active, my activity score can shoot up into the high 90s:

However, I can only get five days of such high levels. Since I need to have at least two recovery days per week, a string of more than five nice days means my recovery suffers once again, turning into lower activity scores.

I haven’t fully characterized the behavior so far, but it seems like the software may well be doing just what the quoted text above says: Getting between 30 and 60 minutes of medium activity makes a day a recovery day, with a hard end to any “recovery” at 61 minutes.

If true, that would probably be the place to make a fix. That is, I’m not trying to suggest that I have any data to show that an average person could walk more than 60 minutes and still recover as well, nor do I have any good metric for identifying some subset of people who can walk more and recover well. But I am pretty sure that the 1 h 3 min of medium activity that I got the day before yesterday is not so much more than the 60 I got yesterday that the former should count as a training day rather than a recovery day.