I’ve long been peeved by how little credit people give to the power of their vote.

I’ve long been peeved by how little credit people give to the power of their vote.

So many people seem to think that a vote isn’t effective unless it holds the balance of power, as if their vote only counted when the other voters were equally split, so that their vote would sway the election one way or the other.

This isn’t true for individuals, and it most especially is not true for groups.

Back in the run-up to the 2008 election, I heard a story on NPR that provided a good counterexample. An Indian tribe in (I think) New Mexico was getting attention from state and national candidates of both parties, because they had started voting. Pretty much all of a sudden, after their voting turnout had shot up, their issues became important to politicians at all levels. And their issues weren’t just important when there was a close election and their votes might make the difference: Because they voted in every election, every politician needed to pay attention to their issues all the time.

If you’re a member of a group that votes, your group’s issues will be taken seriously. You don’t need to be a majority. You don’t even need to vote as a block. (In fact, it’s probably better if you don’t: You want politicians thinking that each individual vote is up for grabs, if they institute the right policies.)

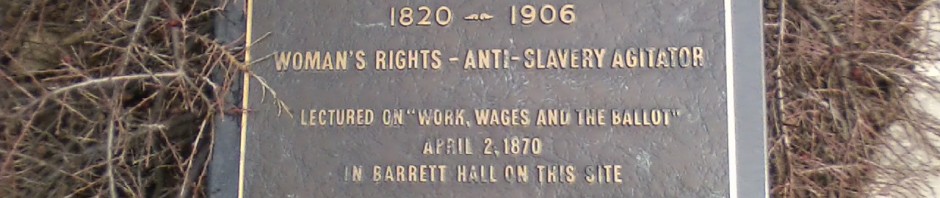

The image at the top of this post is of a plaque in downtown Champaign, commemorating a lecture on “Work, Wages, and the Ballot,” that Susan B. Anthony gave here back in 1870. I’ve seen the plaque many times, but couple of days ago, I thought to take a picture of the plaque, and that prompted me to do a proper search, which yielded some results.

This Project Gutenberg Book Susan B. Anthony: Rebel, Crusader, Humanitarian, by Alma Lutz is pretty good:

She had at hand a perfect example in the unsuccessful strike of Kate Mullaney’s strong, well-organized union of 500 collar laundry workers in Troy, New York. Aware that Kate blamed their defeat on the ruthless newspaper campaign, inspired and paid for by employers, Susan asked her, “If you had been 500 carpenters or 500 masons, do you not think you would have succeeded?”

“Certainly,” Kate Mullaney replied, adding that the striking bricklayers had won everything they demanded. Susan then reminded her that because the bricklayers were voters, newspapers respected them and would hesitate to arouse their displeasure, realizing that in the next election they would need the votes of all union men for their candidates. “If you collar women had been voters,” she told them, “you too would have held the balance of political power in that little city of Troy.”

I turned 18 shortly after the voting age in the US had been lowered to 18. The drinking age had been lowered along with it, so it was legal for me to drink. But a big jump in drunk driving accidents prompted many states to raise their drinking age.

In Michigan it turned out to be an oddly complex process. A state law was passed, raising the drinking age to 19, but grandfathering in people who were already old enough to have started drinking before the law went into effect. After that law was passed, but before it went into effect, a state constitutional amendment was put on the ballot, that would raise the drinking age to 21, without any grandfathering. That would create a whole cohort of people who’d been able to buy alcohol for a year or more, who would lose that right. And all of them could vote.

I voted against it, of course. But nobody else I knew who was going to be in the affected group bothered to vote. They didn’t much care about the issue—it was as easy for under-age drinkers to buy booze then as now—and they didn’t think their vote would count for much. And, as it turned out, they were right. But only because their peers didn’t vote. Not only could a solid voting block of 18-to-20 year olds have affected the outcome, I rather doubt if the issue would have even gone on the ballot, if 18-to-20 year olds voted at the rates that senior citizens do.

The way voting helps is not by winning individual elections (although that does happen and it’s nice when it does). The way voting helps is that if you’re a voter, politicians take your interests into account all the time.