[This article originally appeared as a guest post on Self Reliance Exchange, but that site no longer exists and the successor site doesn’t seem to be using my post. Rather than just let the article disappear, I figured I’d post it here.]

There’s a reason we don’t see more self-sufficiency: It’s not frugal. It almost always takes more time to make something than it takes to earn enough money to buy one—and that’s without even considering the time it takes to learn the skills (let alone the cost of tools and materials). On the other hand, frugality is a powerful enabler for self-sufficiency. So, how do you find the sweet spot?

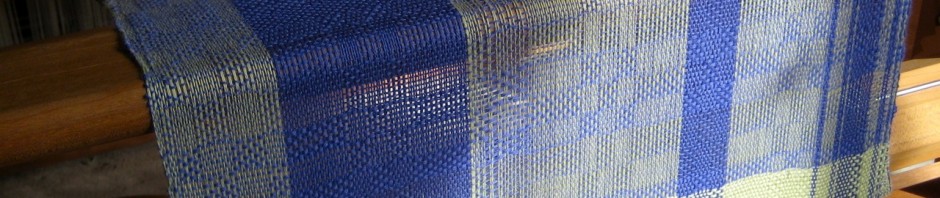

My wife spins and weaves. I have a beautiful sweater that she hand knit from hand spun yarn. It’s wonderful—and it’s comforting to know that my household is not only self-sufficient in woolens, we produce a surplus that we can sell or trade. But the fact is you can buy a perfectly good sweater at Wal-Mart for less than the cost of the yarn to knit it.

If you try to be genuinely self-sufficient—in the sense of producing through your own labor everything your household uses, like a hunter-gatherer or a subsistence farmer—you’re going to be poor. Your neighbor who works at a job for wages or a salary is going to be better off by almost every measure.

Oh, his factory-made microwave meals won’t be as good as home-cooked food from your garden and his furniture from Ikea won’t be as good as what you make in your wood shop. But he’ll have so much more! In the time it takes you just to build a kiln he’ll earn enough money to buy a thirty piece set of Corelle ware. Unless he’s only making minimum wage, he’ll probably have enough left over to buy an iPod—and you’ll never be able to make your own iPod from sand and vegetable oil.

That’s why we have trade. If everybody specializes in one or a few things, and then trades with others for what they need, everybody can be better off. It raises your standard of living, but it means that you can’t be self-sufficient.

There are still many reasons to do for yourself. You can make exactly what you want, instead of having to make do with whatever happens to be available on the market. You can use superior materials, and take them from the environment in a sustainable manner. You don’t have to worry that the stuff you use was made in a sweatshop by children or prisoners or slaves. You aren’t dependent on the continued smooth functioning of the vast global economy. But you can’t be self-sufficient in very many things—even if you had the skills and the tools and the land, you’d quickly run out of time.

So, we find ourselves trying to figure out where we belong on the continuum between actual self-sufficiency and ordinary self-reliance. How do you find the sweet spot? Here are my thoughts:

- Focus on necessities. It’s a lot more important to be self-sufficient in food, clothing, and housing than it is to be self-sufficient in tennis rackets and rollerblades.

- Focus on capabilities. Instead of trying to fill your pantry by hunting and fishing, do enough to maintain and improve your skills—and then start developing your next capability.

- Focus on what’s practical. It’s really hard to be self-sufficient in window glass and impossible to be self-sufficient in digital watches. Don’t waste your time.

Start with the few things where homemade actually is cheaper, like gardening. Then move on to things that can be done as a hobby—and that you’d enjoy doing as a hobby. Don’t let point #1 above (necessities) keep you from developing self-sufficiency in something that’s fun and interesting just because it’s not important. It may not be important to be self-sufficient in beer, but the equipment is cheap, brewing is a pretty easy skill to acquire, and the result is better than what you can buy.

Finally, remember that there’s a vast range between being “self” sufficient and being dependent on a global supply chain. It’s almost as good as self-sufficiency to source things from your neighbors. Short of that, it’s still an improvement to source things closer rather than farther—your home town, your region, your state, your country.

Once you set your priorities, don’t hesitate to go with the cheapest option for things that don’t make the cut. That frees up money that you can use on the important underpinnings of self-sufficiency—things like land and tools in particular, but also things like books, training classes, materials to practice with, and so on.

Then you’re in your sweet spot.