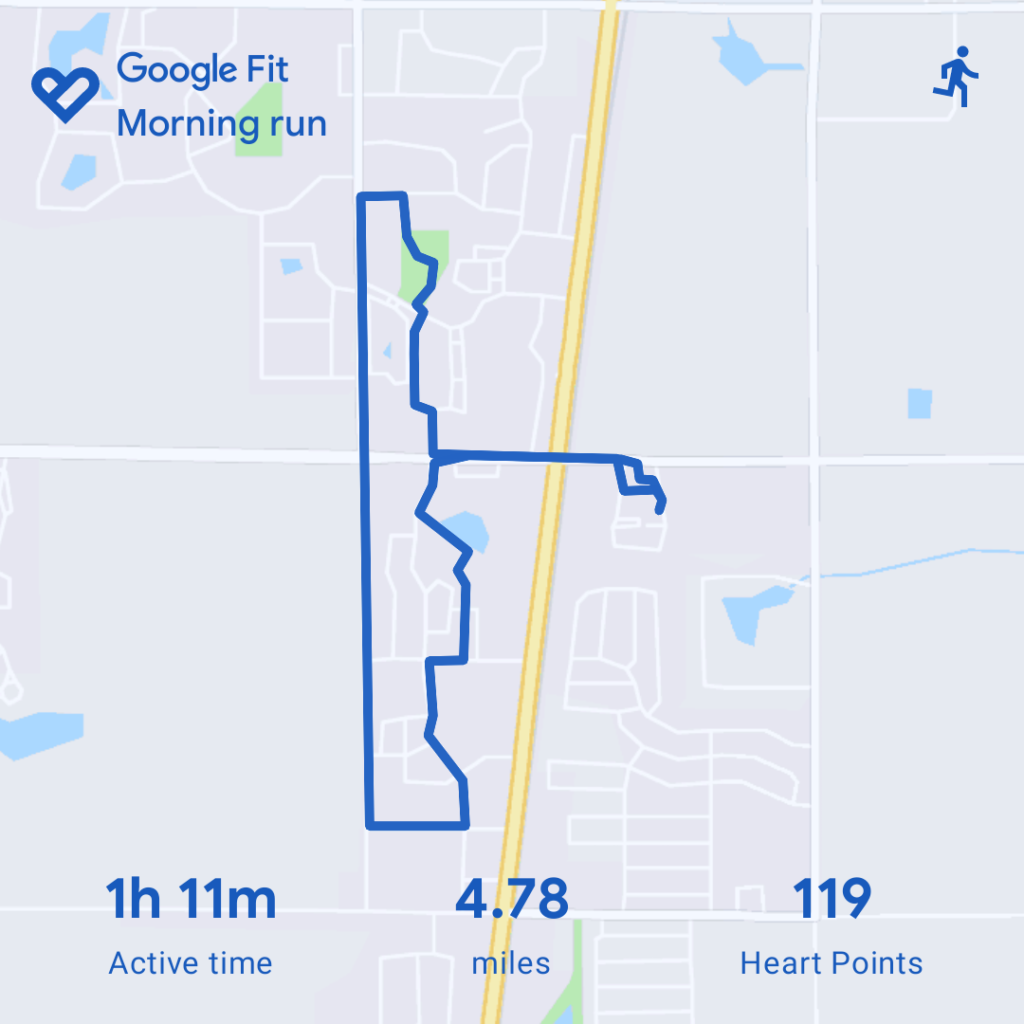

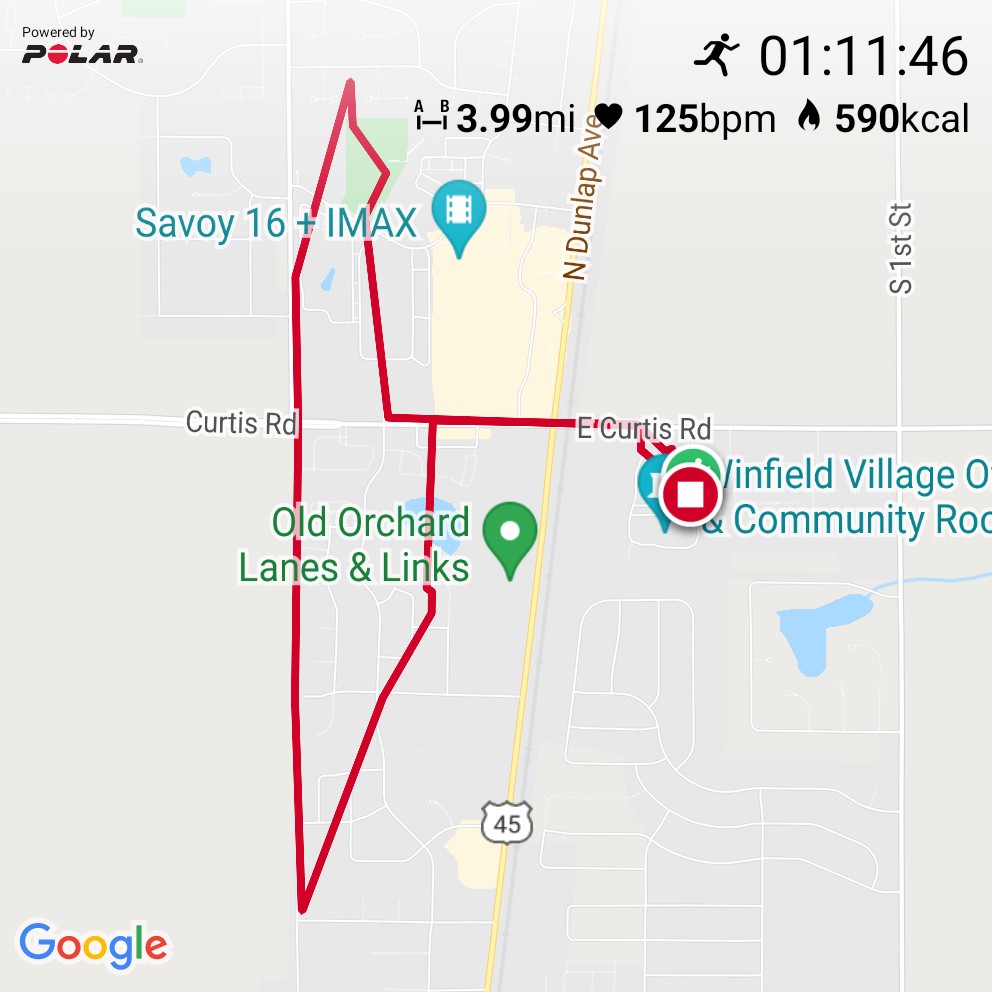

Sometime in the summer of 2020 GPS 🏃🏻♂️ tracking in the Polar Flow app on my Android phone suddenly started producing crappy results.

Polar shortchanges me by nearly 20%!

Sometime in the summer of 2020 GPS 🏃🏻♂️ tracking in the Polar Flow app on my Android phone suddenly started producing crappy results.

Polar shortchanges me by nearly 20%!

Since 2015, when Christopher McDougall’s Natural Born Heroes introduced me to the work of Phil Maffetone, I have not tried to work on running faster. Instead, I have focused on building a really solid aerobic base. Specifically, I have tried to run at a speed that kept my heart rate near 130 bpm (which was the MAF heart rate I came up with back then).

The theory is that, by training at that heart rate, you will gradually increase the speed at which you can run at that heart rate: You get faster at that particular level of effort. Basically, you persist with that—doing your runs at that heart rate—for as long as your speed increases. Only then do you add speed work (intervals, tempo runs, etc.), and then only as a few percent of your training.

In my own rather casual way I took all that to heart. I never did much speed work anyway, but I was happy to just not do any while I waited for the magic of the MAF system to kick in. But it never did. For the past five years I’ve been running very slowly (call it a 15-minute pace) at a nice low heart rate, but I’ve seen none of the gradual improvement that was promised.

I can’t really call it a failed experiment. I’ve enjoyed these slower runs. I’ve largely avoided injuring myself. I’ve built a solid aerobic base. But I’d like to be able to run faster, and following the MAF system doesn’t seem to have done the trick.

So I’m going to gradually ease back into running faster. I’ve done a little sprinting right along (more as strength-training for my legs than in an effort to work on running faster), and I’ll boost that up just a bit. But the main thing I’ll do is just run faster whenever I feel like it.

For years now, I’ve made it a practice to try to notice when my HR goes above 130, and ease up whenever it does. I might still do some runs like that—it does help me refrain from going out too fast and ending up exhausted halfway through a planned long run. But I think I’ll go back to just intuitively running at whatever pace suits me in the moment.

I did that today, and ran 3.16 miles in 43:16, for an average pace of 13:38. Not fast. But I wasn’t trying to run fast—I just quit deliberately slowing down anytime I noticed my heart rate was over 130. For this run my heart rate averaged just 134, so I wasn’t really pushing the effort. Maybe I can still run 12-minute miles!

(By the way, I wrote about Christopher McDougall’s Natural Born Heroes in a post on it and a few other human movement books.)

Choose your sport, get an evidence-based, sport-specific warm-up to reduce the risk of injury: Skadefri by the Oslo Sports Trauma Research Center.

How did I not already know about this?

I captured three videos of my exercises today. They’re mostly for my own use (to look at my form), but I thought I’d share them here as well.

Content warning: I didn’t mute the audio on these, so you get to hear quite a bit of me groaning through the final two or three reps of each exercise. If you don’t want to hear that, you’re advised not to play these.

When I first attempted plyo-lunges two or three years ago, I gave up after a single attempt. It was clear that I was endangering my ankles, knees and hips, because I had no control whatsoever over that move. Over the next couple of years, as I worked on the basic lunge and then the walking lunge, I tried a plyo-lunge a couple more times, without feeling like I had good control—until a few days ago when I figured out what I was doing wrong.

If you’re not familiar with the move, in a plyo-lunge you lower yourself into a lunge, and then from the bottom jump, switching feet in the air so that you land with the opposite feet forward and back, and lower yourself into a lunge position on that side. They’re also called jumping lunges or scissor lunges.

The error I was making—which seems kind of obvious, now that I’ve figure it out—is that I was somehow imagining that I should jump from the bottom of a lunge on one side to the bottom of a lunge on the other side. Of course, that’s crazy. What I need to do is jump from the bottom of the lunge on one side to the top of a lunge on the other side, and then sink to the bottom of the lunge on that side, before repeating.

Once I made that my intention, all of a sudden I felt like I was moving with adequate control. I still need some practice to do the move smoothly, and some increased explosiveness to do it well, but it no longer feels like I’m endangering all the joints of my lower body (and possibly my life) on each attempt.

(I’m making the effort because plyo-lunges seem worthwhile for working on adding some sorely needed explosiveness to my lower body, but also because they’re a component of the Superhero Bodyweight Workout that I’m hoping to do this year, after last year ended up being a bust.)

It was very nearly warm enough to wear shorts and a t-shirt. (That is, I did wear shorts and a t-shirt, and I was nearly warm enough. Nearly.) And in roughly the same sense, it is nearly spring! 🏃🏻♂️

I saw #writerslift on a twitter profile, and thought I’d found a community of writers who also lift weights. But no.

Someone should make an anime series that’s just training montages. Sword-fighting training. Rock climbing training. Running. Martial arts. Always training for some competition or danger, but the series skips those and just goes on to the next training montage.

TIL that “protean” and “protein” are spelled differently. (I knew meanings and pronunciations; I just assumed they were spelled the same, like record and record).

Incidentally, I also bought @TheBioneerʼs new e-book: SuperFunctional Training 2.0: The Protean Performance System.

“The research team discovered that 35 days of continuous exercise improved learning and memory deficits in the aging animals.”

Source: Optimal levels of exercise reverse cognitive decline in mice

I’m afraid I’m not up for 35 days of continuous exercise. Probably not even 35 hours.