I’m considering registering for the Rattlesnake Master Run for the Prairie 10k coming up in just over a month. Ahead of any race it makes sense to do a bit of speedwork. And I wanted to do a little test, to make sure I’m up for running hard for (close to) that long. So I did.

I always hesitate before I call a workout “speedwork,” simply because I run so slowly, but really, anytime you run faster than usual, it counts as speedwork.

I do two sorts of speedwork. Sometimes I do sprints (either on the flat or uphill). Other times I do what I did today, which is perhaps a tempo run or perhaps a lactate threshold run—I’m not sure which is a better description.

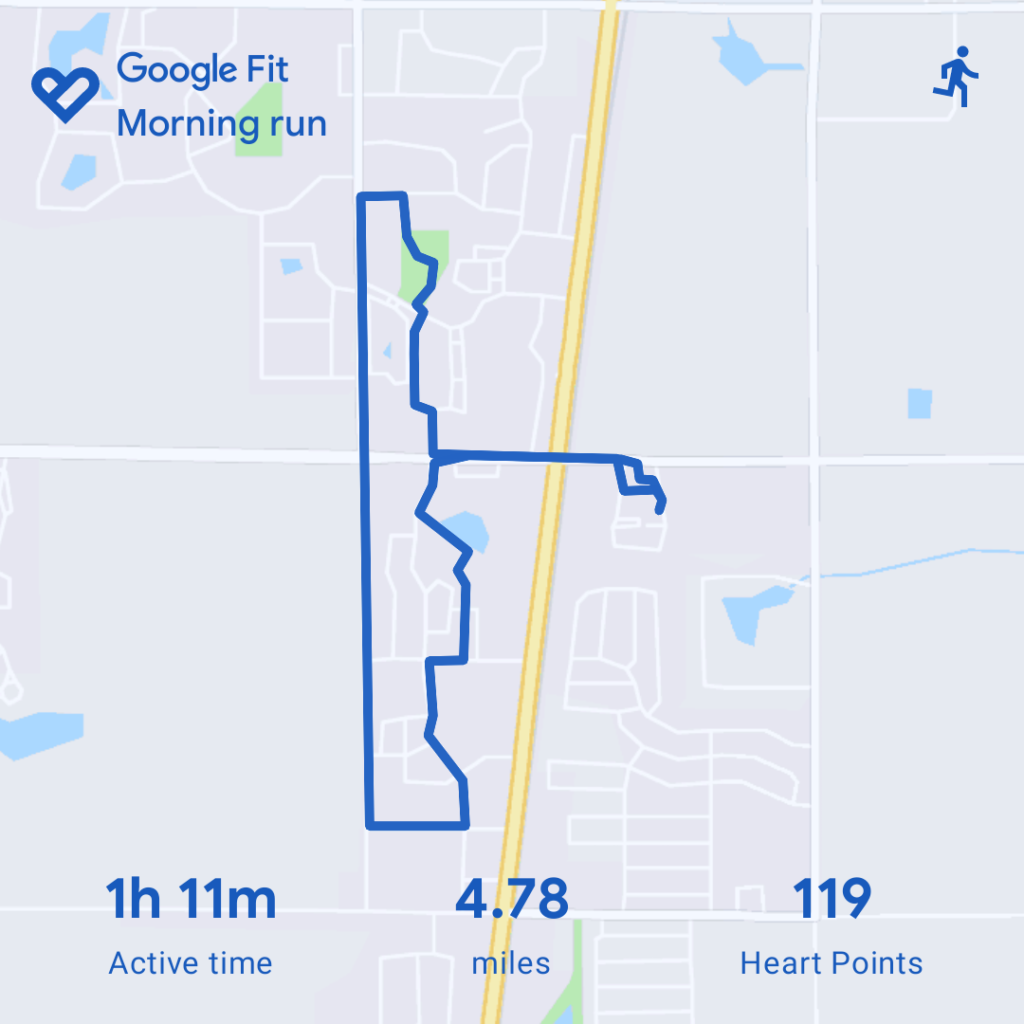

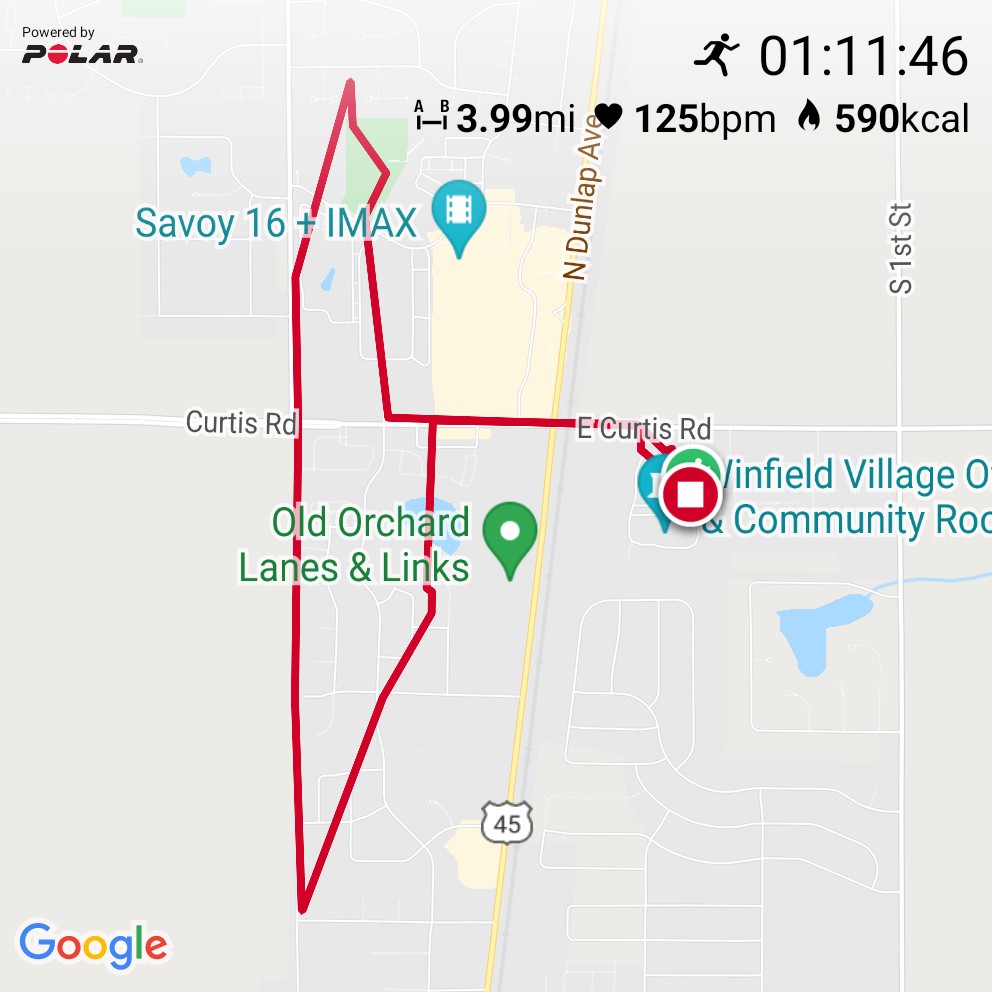

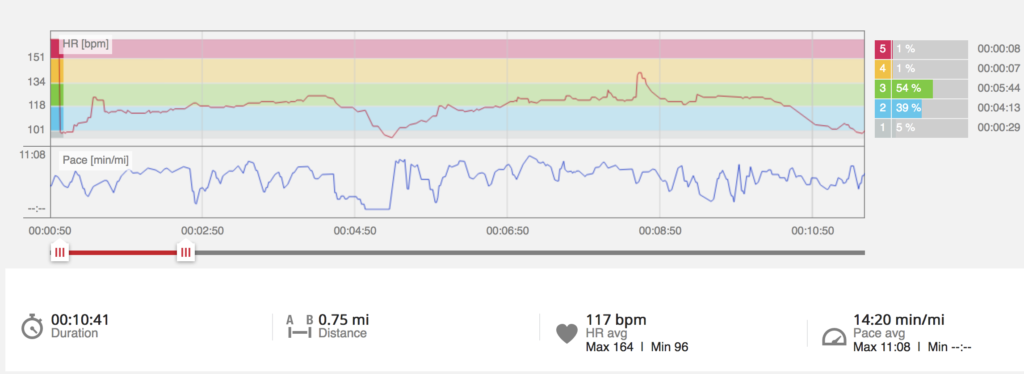

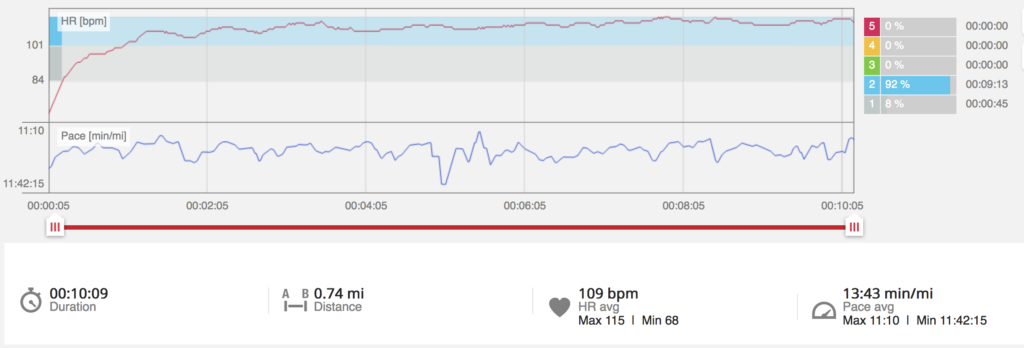

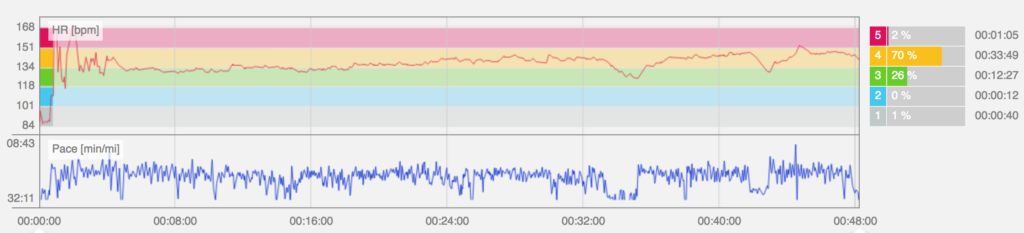

What I actually did was set out to run at the fastest pace I could maintain for an hour. The whole run came in at 5.19 mi in 01:08:43, so an average pace of 13:13 min/mi. That included some easy minutes to warmup at the beginning, and then some cooldown at the end. The core part of the workout (which was intended to be 1 hour) came in at 4.58mi in 00:58:50, so an average pace of 12:50 min/mi.

I’m actually pretty pleased with that. For around six years now I’ve been trying (for almost all my runs) to keep my heart rate low enough that the exercise is almost entirely aerobic. The target HR for that is given by what’s called the MAF 180 formula. (The formula is 180 minus your age, and then with a few modifiers, which for me would include another minus 5 because I’ve gone back on blood pressure meds.) So I should probably be trying to keep it under 112 bpm. Boy would that be slow.

Years ago I came up with 130 bpm, and had never updated it. I usually keep my HR down around 130 for the first two-thirds of a run, after which it tends to start creeping up.

To hit those low heart rates I had to run pretty darned slowly: I averaged maybe 16 min/mi, which put my running speed down into the range of a fast walk. (Actually, very slightly faster than that. When Jackie and I were training for our day-hike of the Kal-Haven Trail we worked on upping our walking pace, to be sure we’d be able to walk 34 miles during daylight, and we got up to where we could do a mile in less than 18 minutes, but I’m not sure we ever walked a mile in less than 17 minutes.)

Back in March I realized that I’d probably been pushing on that one lever (workouts at a low heart rate) for longer than made sense, and I started easing back into running faster for at least some of my workouts, and this is one where I tried to go a bit faster.

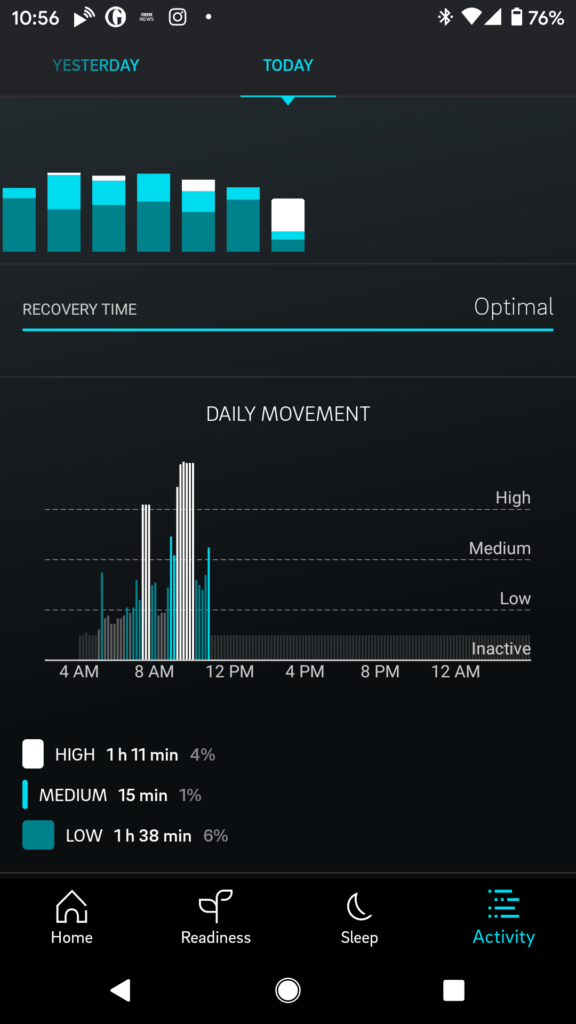

For this run my HR (excluding a few glitchy readings before I got sweaty enough for my HR monitor to work well) averaged 141 and maxed out at 151.

I looked back at this blog for reports of my running pace at various times, and found that I used to routinely break 12 min/mi, but all the specific reports I found were for runs under 3 miles. I did find that the previous time I ran Rattlesnake Master Run for the Prairie I ran it with an official time of 1:17:13.4 meaning a 12:26/mile pace.

At any rate, I’m pretty pleased with this run, both as a test, and as a bit of speedwork ahead of next month’s Rattlesnake Master Run for the Prairie, which I’m now considering a little more seriously.