I’m only rarely in shape to run 7+ miles, and even more rarely in shape to do it in the winter. 🏃🏻♂️

I spotted this toy in mile 4, and paused to get a photo.

I’m only rarely in shape to run 7+ miles, and even more rarely in shape to do it in the winter. 🏃🏻♂️

I spotted this toy in mile 4, and paused to get a photo.

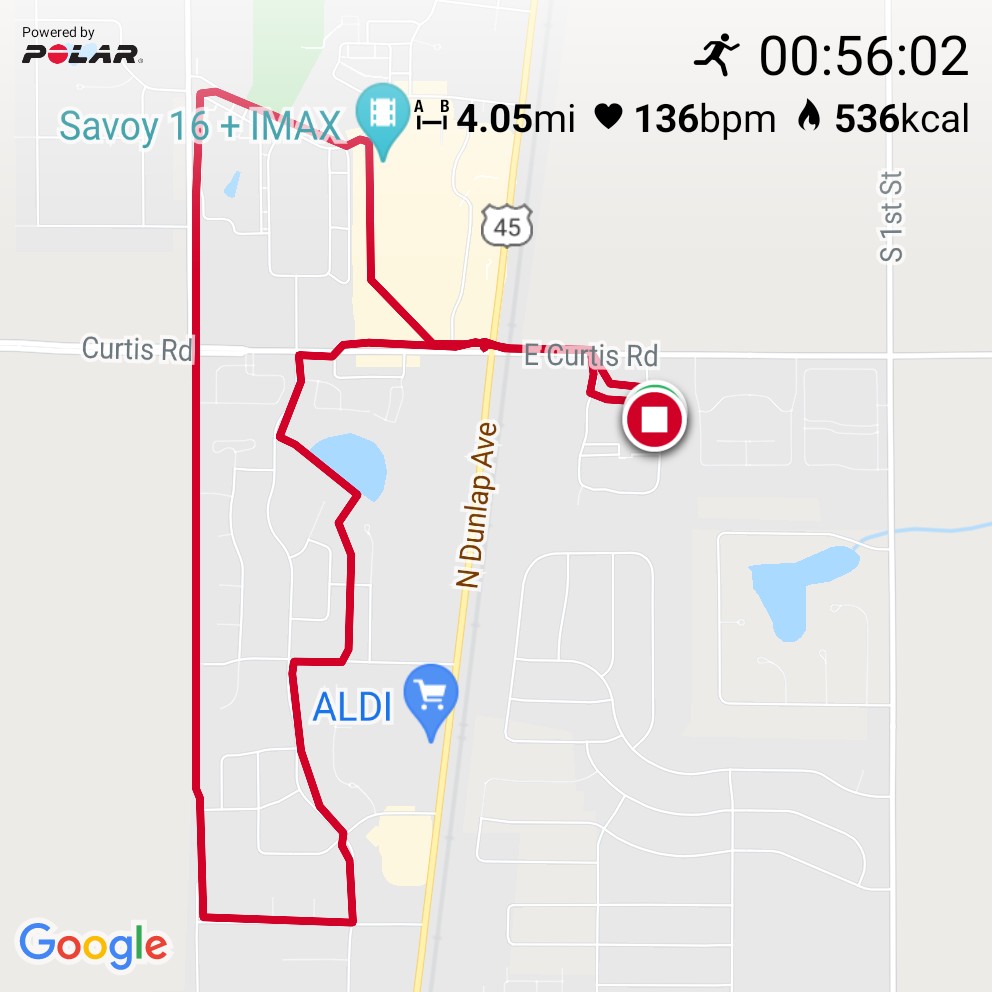

On Friday I did a 4 mile run. 🏃🏻♂️ Around half way, a Red-tailed Hawk flew low over my head and struck at prey in the lawn across the street. Then, before I could get my phone out, flew up into a tree. You can see it there: the bird-shaped smudge about 2/3rds up.

Two writing sessions got me 1,067 words, and brings me to nine #amwriting days in a row. Now I need to rush through my morning exercises if I’m going to get in my workout in time to grill steaks for lunch. 🏋🏻♂️ ✍️

It’s a bit harder to put this past year in a tidy descriptive box than it has been the past few years. Probably the simplest description would be: The same, but less so.

Last year I did a great job of leaning into exercise as a way to cope with the pandemic. This year started with me feeling like I could imagine that the pandemic would end, and I was focusing of all the new things I could do, once I could spend time with other people—rock climbing, parkour, fencing, historical European martial arts (i.e. sword fighting), etc.

Except then the pandemic didn’t end, and I was left to carry on as best I could with last year’s exercises. I did okay, but not as well as I had done.

In fact, I’m perfectly pleased with the way I maintained my capabilities. Late last year I checked and documented that I’d pretty much accomplished the baseline goals that I’d set for myself (see Five years of parkour strength training). I just checked again, and I’ve not backslid on those.

Last year I didn’t even think about setting new baseline goals, because my plan had been to move on from these solo training goals to training with other actual people. This year I’ve felt like I needed to at least think about it, but so far I’m not feeling it. I do want to recover the ability to do a few pull ups (again!), but that’s about the only physical benchmark of that sort where I feel like I want or need specific improvement.

It’s not that I’m a perfect physical specimen; it’s just that I don’t have much attachment to being able to squat this much weight or deadlift that much. I want to be strong enough to pick up something heavy and carry it a reasonable distance, but I don’t feel much need to put specific numbers on that weight or that distance.

I wrote a day or two ago about how I gradually shifted to more running and less lifting, which has been great. But in the middle of the year I spent some months doing less of everything—I had a minor medical issue in the spring, then we took a vacation, then I went to visit my dad, then Jackie had her hip replacement (meaning that I had to pretty much take over running the household for a few weeks). I did okay in terms of not backsliding too much, but I didn’t make much forward progress, and it has only been in the last six weeks or so that I’m really getting back to doing what I want to do.

So, where to go from here? I guess I want to:

I’ll aim to do something just like that in January and February. Along about March or April I will want to do the Superhero workout that I couldn’t do last year—that’ll be a brief interruption in my shift back to more running and less lifting, but just for eight or nine weeks. In mid-summer we have a plan for a hiking vacation in North Carolina, so in May and June we’ll want to gradually boost the amount and speed of our walks, and be sure to include plenty of hikes on trails, and to get in as much elevation change as possible in Central Illinois. I’ve got a couple more trips planned for late summer (assuming the pandemic allows), including attending WorldCon, but it’s only the hiking trip that will have much influence on my movement strategy.

So, I guess I have a plan.

My “fast” run for this week was just an ordinary 4-mile run, except around the midpoint I set my interval timer and did all-out sprints 5 x 10″ with 50″ recovery. 🏃🏻♂️

This is the fourth week in a row where I actually did both my “long” run and my “fast” run—always my intention, but rarely achieved earlier in the year. 🏃🏻♂️

I started practicing tai chi in 2009 with a beginner course at OLLI (the OSHER Lifelong Learning Institute). I’d always been attracted to tai chi. I liked the way it looked—the slow, controlled movement. I was also interested in it as a martial art, and I liked the idea of “moving meditation.” Despite all that interest, I had not anticipated how transformative the practice would turn out to be.

Before I added the tai chi practice to my life, I was all about figuring out the “right” amount of exercise—and in particular, the minimum amount of running, lifting, walking, bicycling, stretching, etc. to become and remain fit enough to be healthy, comfortable, and capable of doing the things I wanted to be able to do.

Pretty quickly after I took up the practice, I found I was no longer worried about that. I found that my body actually knew what the right amount was, and that all I needed to do was move when I felt like moving—and make sure that my movement was diverse.

Because diversity was the key, I did a lot more than just tai chi. I continued running. I dabbled in parkour. I stepped up my lifting practice (and then shifted to mostly bodyweight training when the pandemic made gyms unavailable, and then continued with it because it seemed to work better). I went down a “natural movement” rabbit hole. I walked a lot.

In about 2012 or 2013 my tai chi instructor asked if anyone wanted to “assistant teach” the beginners class with him. I volunteered, and then did so. After six months or so he asked me to take over the evening class that he was teaching for people who couldn’t come to the early classes. I gradually started filling in for him on other classes as well.

In 2015 I formally took over as the tai chi instructor at the Savoy Rec Center. I really enjoyed teaching tai chi, although I found the constraints (having to show up at every class) a bit. . . constraining.

I did some tweaking around the edges (in particular, combining the Wednesday and Friday classes into a single Thursday class, so I could have a three-day weekend), which helped, but only so much.

Then a few weeks ago, the Rec Center wanted me to sign a new contract which would have required me to buy a new insurance policy, naming the Village of Savoy as an “additional insured.” I’m sure I could have done that—there are companies that sell insurance specifically for martial arts and fitness instructors. But as soon as I got set to research such policies, I realized that I really didn’t want to.

Instead, I wanted to retire.

I’d retired from my regular job years before, in 2007. And of course teaching tai chi four or five hours a week was in no way a career. The first few years I was teaching, I found the money I earned a nice supplement to our other retirement income. But with various improvements to our financial situation over the last few years, the money became pretty irrelevant, and the time constraints more. . . constraining. Especially with my parents facing various health challenges, I want to be able to go visit either one if that seems necessary, which has been difficult if I want to honor my obligation to my students.

So a few weeks ago I told the Rec Center and my students that I was retiring from teaching tai chi. My last classes were yesterday.

I’m sad not to be teaching my students any more, but delighted at losing the set of related constraints.

For years now, my students have been gathering in the park (Morrissey Park in Champaign, Illinois) during nice weather for informal group practice sessions, and I expect we’ll keep doing that. At any rate, I plan to be there, starting in the spring, practicing my tai chi. You are welcome to join us.

For years I had trouble running into the winter. I eventually figured out that I’d simply had the wrong idea about how to do it. I’d imagined that if I just continued running through the fall, I’d gradually ease myself into winter running. That never worked—because there are plenty of warm days (or at least warm hours) through early fall, and then in middle or late fall there is (identifiable only in retrospect) a last warm day, and then it’s cold nearly every day until late March or early April. So even if I ran through fall, if I chose to get in my runs during the warm hours, I wouldn’t actually develop tolerance for the cold, the wardrobe for handling it, or the skill at picking the right garments.

A couple of years ago I failed to run through the fall, and then decided to develop a winter running habit anyway. I bought a few pieces of cold-weather gear—plenty, because I was generally only running once or twice a week.

I started with the sweats I wear to teach taiji, and then I added two pairs of tights—one sort of classic running tights, and then another pair of fleece tights, that ought to be good down to colder than I’m every likely to try to run in.

For tops I generally wore a regular sweatshirt over a regular cotton t-shirt. Then I got some short- and long- sleeved merino t-shirts, which are vastly better as a base layer. I also dug out a capilene half-zip top that my dad gave me a few years ago, which was just the thing when it got a little colder.

I also got a washable merino knit hat in high-viz yellow, and two different pairs of gloves in high-viz yellow—first a pair from the dollar store, which were not nearly warm enough, then a pair from Amazon that I think was marketed to people directing traffic, that were dramatically more high-viz, but still not quite warm enough.

Now that I’m in my third year of winter running—and now that I’m running more times per week—I’ve added a few more pieces of winter running garb.

I bought a third pair of high-viz gloves, these from Illinois Glove company, which are finally warm enough, and almost as high-viz as the previous pair.

Last winter I picked up a pair of Janji Mercury Track Pants, which are wonderful. Size medium fits me perfectly, they’re warm enough down to well below freezing (and I rarely run when it’s below freezing, because of slipping hazards). I liked them so much I picked up a second pair last year, and just now got a third pair (because a couple of weeks ago I wanted to go for a run and both of the first two were already in the laundry).

Last year I added another quarter-zip pullover in some high-tech fabric that I picked up cheap at Amazon, and just now today another fancy Patagonia capilene base-layer top that I can wear either by itself, over one of my merino T-shirts, or under a wind-proof or water-proof layer.

I’ve gone running five or six times in the last couple of weeks, at temperatures ranging from right at freezing up to maybe 50℉, and so far I’ve managed to nail it each time as far as matching the warmth of the clothing to the conditions outside.

I have one more piece of running gear that I’ve ordered, but that hasn’t arrived: a headlight. Normally I just don’t run when it’s dark. (Since I don’t work a regular job, I have the freedom to choose to run only during daylight.) But a couple of times in the last few weeks, I wanted to go for a run that would start in the daylight, but might not finish until after dark. I figured that a headlight might be very useful as a just-in-case piece of safety equipment, even if I didn’t plan on doing much nighttime running. I ordered this Spriak Wide-Beam headlight, which seems like it would serve my purpose as emergency safety gear. If I end up running in the dark on purpose, rather than by accident, I’ll be tempted to step up to this Petzl Headlamp that offers 3x to 15x the battery life, and what looks like a rather better system for fitting the whole thing on your head, but costs 10 times as much ($200 vs. $20).

(FYI: Those Amazon links are affiliate links. The non-Amazon links are not.)

If circumstances develop in any sort of interesting direction—if it turns out that the gear I’ve got doesn’t cut it for this or that sort of conditions, or if I decide that I need some other bit of fancy running kit, or if one of the things I’ve got turns out to be even more suitable than I’ve already described, I’ll go ahead to write another post.

If you’ve got great winter running gear, I’d be very interested to hear about it! Comment below or reach out on social media or by email (see my contact page for ways to connect to me).

As I have been saying for years. But the myth that “running will ruin your knees” is pretty tough to get past.

“cartilage is a living tissue that adapts and thrives with regular use”

Source: How to Save Your Knees Without Giving Up Your Workout — NYT

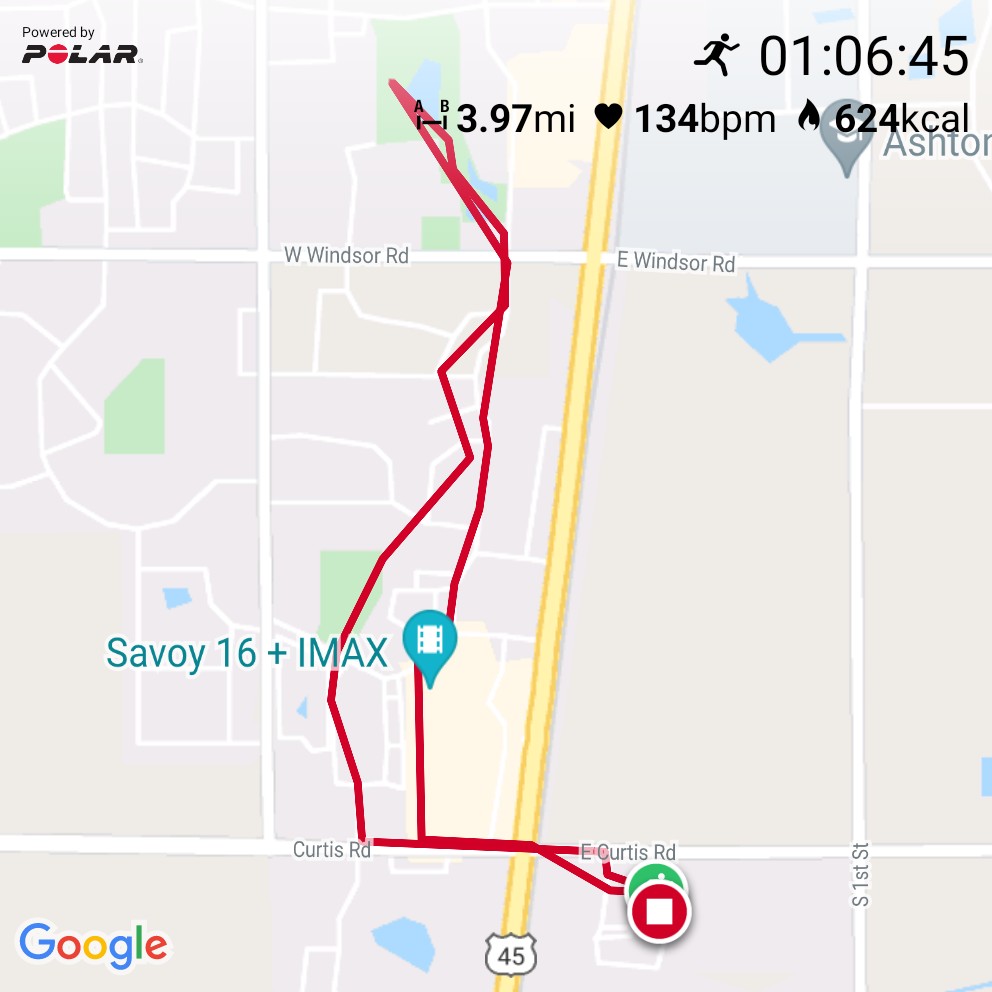

My workout was a medium-length run of 3.97 miles which I ran in 1:06:45, but that was not my only activity. Besides that, I also hiked a similar-length trail at Homer Lake with Jackie.

The walk was especially nice, and we’re very pleased that (with her new bionic hip) Jackie is once again able to walk reasonable distances. We walked about 2.72 miles in 1:24. There were some very nice views of Homer Lake, as well as some deer, some blue jays, and a handsome snek that I failed to get a decent picture of.

I did get a decent picture of Jackie:

Besides the pictures from Homer Lake, I also got a picture of a handsome Red-tailed Hawk while I was out running, taken quite close to home. (See at the top of this post.) He was still there as I returned home.

I should mention that the run was actually quite a bit longer than my exercise-tracking app gave me credit for. (Google Fit estimates the distance at 4.46 miles.)

You can get an idea of just how much my exercise-tracking app shorted me from this map, if you know that I ran around the lake at the north end of of my run (and not as the map suggests, through it), and that I generally followed roads and paths (without cutting nearly as many corners as the map suggests).

I want to reassure people that I will not be posting all of my workouts going forward. I just wanted to post a representative strength training session and run, so that I’d have then here as examples.