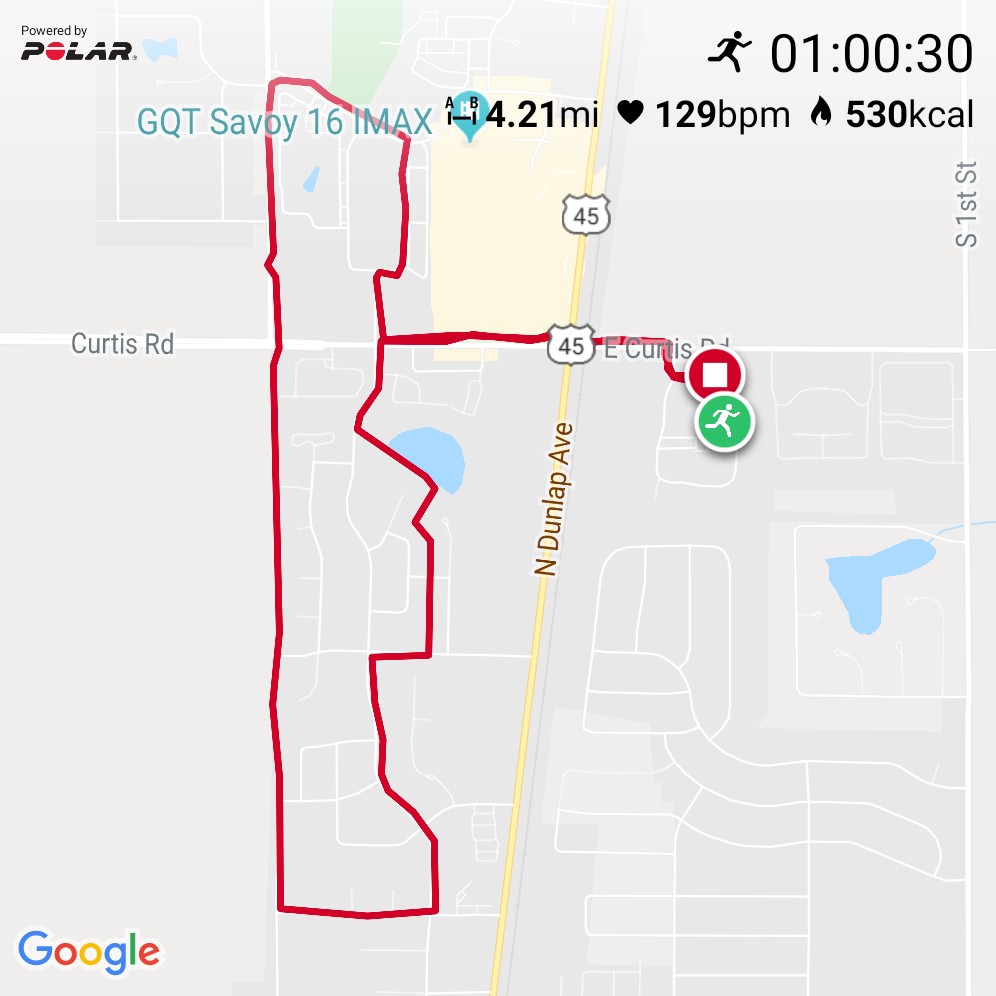

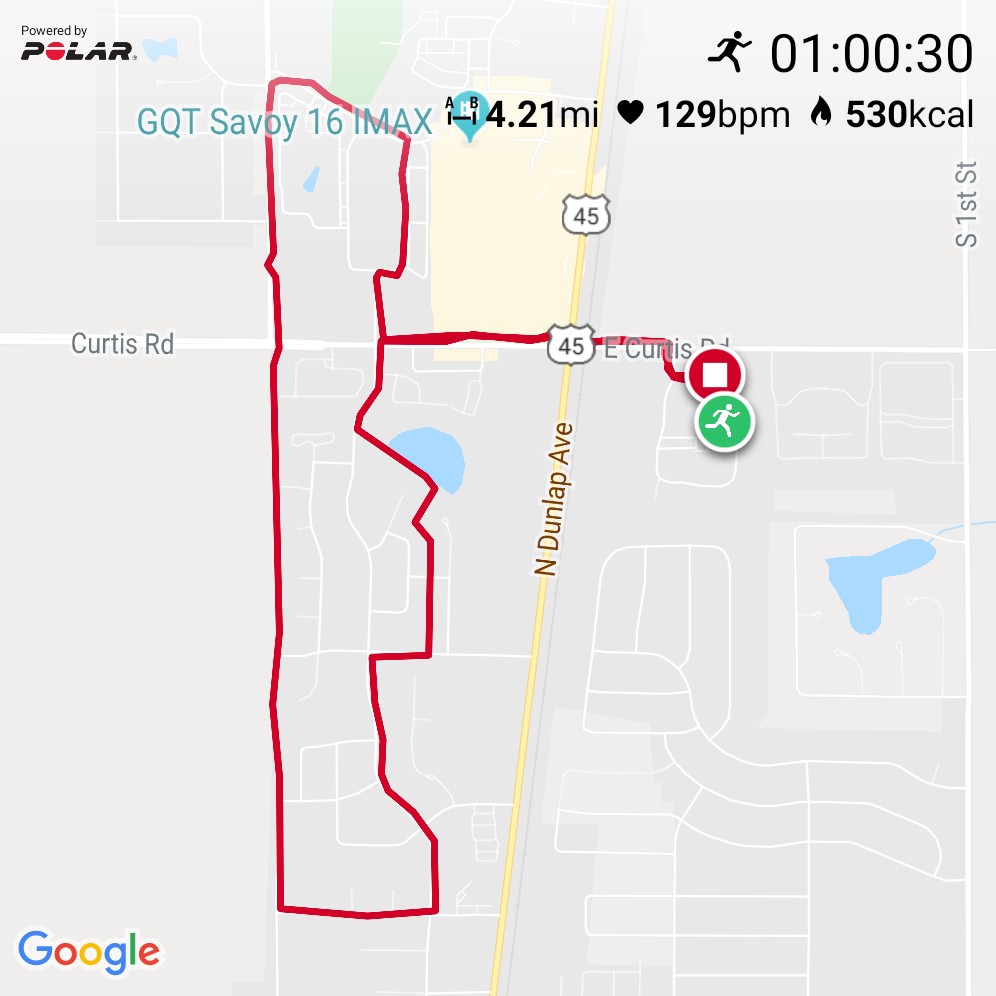

Great run! My sore foot didn’t hurt until I was just a few steps from home. My knee didn’t hurt at all. My heart rate held exactly where I wanted it.

Great run! My sore foot didn’t hurt until I was just a few steps from home. My knee didn’t hurt at all. My heart rate held exactly where I wanted it.

Latest in the long-running series, “Studies that reinforce my preconceptions just from reading the headline”:

Vegans have twice as many sick days as their meat-eating colleagues in the UK, according to a new report.

Source: Report finds vegans have twice as many sick days as meat-eaters

After the Rattlesnake Master 10k I came down with either a very nasty cold or else a moderately nasty case of the flu. Whatever virus it was, it had me pretty much down for the count for a solid week. Today was the first day in almost two weeks I felt up to a run.

On Sunday I ran in the Rattlesnake Master Run for the Prairie 10k.

Usually I expect that I’ll write a post when I participate in an event like that, but it turns out that I don’t have a lot to say about it. It went fine. I ran very slowly, which I expected because I’d done all of my training very slowly, but I did not come in last, which was nice.

I’d suffered with a nagging sore foot for several weeks leading up to the race. The pain was in the heel of my right foot, which made me figure it was probably plantar fasciitis. I think I’ve figured out though that it’s actually peroneal tendonitis. Understanding that gives me a clue toward recovery. The peroneal tendon, which reaches down the outside of your ankle, through the heel, and then forward across to the inside edge of the front of your foot, is heavily involved in balancing, especially standing on one foot. I do a lot of single-leg standing as part of my taiji practice and teaching, and since figuring this out I’ve been especially careful about being gentle with myself in this part of the practice, and in just a few days I’ve finally seen dramatic improvement.

The realization didn’t help in time for the race though, and my foot was a little sore right along. It wasn’t so sore that I thought I was doing real damage though, so I just ran the race anyway. It did impact my gate a bit, which meant that my opposite-leg knee started hurting about halfway through the race.

Part of the reason for this post is to test the GPX exporting at Polar (which had been broken for a while) and the GPX tracking plug-in that I’ve got here (which has been updated a couple of times since I last successfully got a GPX track exported from Polar). So, here’s the track of my run. The heart rate data doesn’t seem to be working.

(I didn’t want to fiddle with my phone at the start or finish of the race, so I started tracking my run about 5 minutes before the start of the race, and then I forgot to turn it off until about 5 minutes after I crossed the finish line, so both the time and the distance are a little off.)

My official time was 1:17:13.4 meaning a 12:26/mile pace. That’s as fast as I’ve run in years. (Overall results. Age-group results.)

It was pretty cold at the start—cold enough that I didn’t manage to get my race number in my pre-race selfie:

It had warmed up a lot by the end of the race, when I captured the selfie up at the top with Jackie (who along with a lot of the Master Naturalists had volunteered in the race).

Another post to file under “all the rays are actinic”:

[Near infrared light] can trigger cellular activities that restore cellular metabolism, promote blood flow, neuroprotection, and reduce levels of inflammation and oxidative stress. All of these cellular mechanisms can be summed up as “helping the brain to repair itself.”

Source: Will the Photobiomodulation Trial Be the One to Turn the Tide Against Alzheimer Disease?

I have always been an optimizer. I spend way, way too much time, energy, and attention optimizing things. Which is, you know, fine, even though my net benefit is small or zero, largely because I don’t focus my optimization efforts in places where I get the biggest payoff. (I’d say that I don’t optimize my optimization efforts, but I don’t want to tempt my brain into trying to do that. It would not end well.)

One place where my optimization efforts did end well has been in optimizing things for life under late-stage capitalism.

I was helped by a couple of lucky coincidences and a bit of lucky timing.

Purely because I enjoyed doing software, I became a software engineer at the dawn of the personal computer era, which gave me a chance to earn a good salary straight out of college, a salary that grew faster than my expenses for most of the next 25 years.

Whether because of my upbringing or my genes (my grandfather was a banker), I liked thinking about and playing with money, which meant that I was doing my best to save and invest during a period when ordinary people could easily earn outsized investment returns.

It worked out very well for me. I’m as well positioned as anyone who isn’t in the 1% to do okay in late-stage capitalism. (Frankly, better positioned than a lot of the 1%, who find it easy to imagine that they deserve the lifestyles of the 0.1%, and if they live like they imagine they should will quickly ruin their lives.)

This whole post was prompted by a great article that looks mainly at the efforts women make to optimize themselves under the overlapping constraints of health, fitness, appearance, and financial success in the modern economy. Highly recommended—insightful and daunting, but also funny:

It’s very easy, under conditions of artificial but continually escalating obligation, to find yourself organizing your life around practices you find ridiculous and possibly indefensible…. But today, in an economy defined by precarity, more of what was merely stupid and adaptive has turned stupid and compulsory.

Athleisure, barre and kale: the tyranny of the ideal woman by Jia Tolentino

One focus of that article is on “fitness.” I put fitness in quotes because of the way, especially for women, so much of fitness is actually about appearance. Perhaps because I’m not a woman—also perhaps because I’m already married, and because I’m older—my own perspective on fitness has gotten very literal: I want my body to be fit for purpose—fit for a set of purposes which I have chosen. I want to be able to do certain things because I have found the capability to be useful. (I also want to be able to do certain things that I can’t do, because I imagine that the capability would be useful, and much of the exercise I do now is intended to achieve those capabilities.)

In a sense, optimizing for fitness is really neither here nor there as far as optimizing for late-stage capitalism, which is mostly about money. And yet, really it is. My fitness suffered during the period I was working a regular job. Getting fit and staying fit takes time. To a modest extent, you can substitute money for time—you can pay up for the fancy gym where the equipment you want to use is more available, or take a job that doesn’t pay as much but allows you to squeeze in a midday run. But now we’re right where we started: optimizing for life in late-stage capitalism.

I should say that I’m delighted with how well my life has turned out. If I’d had any idea how little I could spend and still have everything I really want, or how early I’d have saved up enough money to support that modest lifestyle, perhaps I could have avoided a lot of anxiety and unhappiness along the way. But who among us has such luck? And more to the point, maybe some of that anxiety and unhappiness were crucial to my making the choices I did that got me to where I am.

I worry just a bit about my irresistible impulse to optimize, but like everything else about me, it got me to where I am. And, as I say, I’m delighted to be here.

Here’s a report on a study which measured vitamin D levels of Hadzabe and Maasai individuals living traditional hunter-gatherer or pastoral lifestyles, the data having been collected with an eye toward learning something about what would have been typical during our evolution as a species.

For the Hadzabe the mean was 109 nmol/l and for the Massai 119 nmol/l. These levels are not outside the reference range, but are way above the minimums.

[T]he mean vitamin D concentration of traditional Africans is indicative of the level that would have been typical throughout much of our evolution, and hence, the level that the human physiology would have grown accustomed to over millions of years. Hence, it’s not unreasonable to speculate that such a level may indeed represent optimality…

Source: The Vitamin D Levels of the Hadzabe and the Maasai: An Important Study That Flew Under the Radar

People not living traditional lifestyles can get enough sun to see similar levels, but probably not if they work in an office, and probably not at all in the winter (unless they live in the tropics).

I had my own vitamin D level measured once. It was 38.5 ng/mL (equivalent to 96 nmol/l) versus a reference range of

As I was observing just a few days ago, when exposed to sunlight, your skin does a lot more than just make vitamin D. I’m pretty sure that high vitamin D levels are just a marker for adequate sun exposure. Taking vitamin D supplements in sufficient quantity to raise your blood levels high enough to mimic those of people who get enough sun will produce no more benefit than gaming any metric does.

I’d be interested to know what my vitamin D levels are right now, after a long summer of getting plenty of sun. But not interested enough to go to the effort of convincing my doctor that it’s worth testing again, nor interested enough to pay for the test.

Many years ago I read a pretty good book: How to Want What You Have by Timothy Miller. It teaches what is basically a stripped down, secularized Buddhism as a way to make yourself happier. I was reminded of it because I’ve just read 10% Happier by Dan Harris, which covers similar material. I’d recommend either book for anyone who wants to be happier.

Reading a book about meditation made me realize that I’ve been meditating (in my own somewhat haphazard way) for a full ten years now. I don’t meditate every day, but for most of the year (while I’m teaching my taiji classes) I meditate at least five times a week.

Some people seem to find their meditation practice immediately reinforcing: the practice helps them deal with real world problems, which makes them more keen to meditate, which helps them even more, in a self-reinforcing cycle.

That hasn’t really been my experience.

I’ve long been inclined to blame that on initially not taking the meditation more seriously, and figure that if I’d just try a little harder to really meditate, rather than just go through the motions, I’d discover that it’s extremely useful to me just like other people find it useful for them.

That’s been true in a small way, but only a small way. And I think reading the Harris book has helped me spot one reason why not. His alternate title was The Voice in Your Head is an Asshole, and a good bit of his (and other people’s) experience of meditation is like that—their internal voices are belittling and denigrating, full of imposter syndrome and criticism. Meditation helps them by helping them understand that their internal voice is not them, and that they can easily go astray by paying too much attention to it.

My internal voice isn’t like that at all. My internal voice thinks I’m great. (I credit my mom for this. She thinks both of her sons are perfect in every way, and will countenance no disagreement.)

My internal voice isn’t without its flaws. It’s way too prone to remind me of things I did that were wrong or mean or unhelpful, as if its purpose were to make me embarrassed or unhappy. It’s also way too likely to get me started worrying about possible bad things that might happen in the future, sending me into a spiral of anxiety or depression. But it doesn’t think I’m bad. Just that bad things have happened in the past (that I should feel bad about) or that bad things might happen in the future (that I should worry about).

So I too can benefit from learning not to pay too much attention to my internal voice. But I don’t get the immediate payoff that comes to those whose internal voice is an asshole, rather than merely occasionally unhelpful.

Having been reminded of the Miller book, I was reminded of the other two legs of its recommended practice: gratitude and compassion.

I’ve made an occasional effort to practice gratitude. Click on the gratitude tag in the sidebar to see any number of instances where I documented a feeling of gratitude. I should do more of that, but I think I’ve gotten pretty good at gratitude, at least compared to when I was a child and had a lot of trouble feeling gratitude for the things I did have when there was so much that I wanted and didn’t have.

Which brings me to compassion. It turns out I have a tag for it too, although there was only one post under that tag before this one, where I wrote about how excited I was that Christopher McDougall’s book Natural Born Heroes was coming out. One of McDougall’s main points is that compassion is a key attribute in a hero, every bit as important as bravery or strength.

The Miller book suggests a specific technique for practicing compassion, which is that whenever someone acts like an asshole, you imagine some reason why their behavior might be excusable, or at least understandable. The guy who cut you off in traffic? Maybe they’re rushing to the emergency room because a loved one was just in an accident. The dude who practically knocked you over because he was staring at his phone? Maybe his boss just fired him by text. The woman who overheard a casual comment in a private conversation and rudely took you to task for it somehow being offensive? Maybe your words reminded her of some past traumatic experience.

I have a friend who used to do this when we were officemates. Whenever I’d complain about somebody—typically for endangering my life with their careless or aggressive driving, but sometimes just for being rude or dismissive or inconveniencing me in some way—he would always have an excuse. Maybe the person was old or sick or injured or in pain or hadn’t slept well. He could always imagine some reason why that person should be excused for their behavior.

It was really annoying.

But I can now feel some compassion for his need to do that. Partially he was trying to help me—help me be less annoyed, help me learn how to feel compassion. But at least as much, I now understand, he was trying to remind himself to practice compassion for the people who made his life more difficult.

Dan Harris describes a specific Buddhist meditation technique for practicing compassion. Called metta meditation, it involves choosing a few compassionate phrases such as “May I be happy. May I be healthy. May I be safe. May I be filled with ease.” In your meditation direct them first at yourself, then at a series of others: a benefactor, a close friend, a neutral person, a difficult person, and then “all beings.”

Time for me, I think, to step up my own gratitude and compassion practices. I think I’ll give metta meditation a try, and I’ll get back to gratitude journaling here on my blog.

I find gratitude easy. I am, for example, grateful for the public art in our local parks. (If you’re an arachnophobe, you should be grateful that I didn’t go with my first impulse, which was to post a photo of the spider friend I saw in the house this morning, to which I’m grateful for its help with insect pests. Relatedly, I’m grateful to my mantis friend! And to a growing number of human friends, such as this human friend with Jackie!)

Compassion will take more practice, I fear. But I think it’s practice I’m ready for.

I observed years ago that the more sunlight I got the better I felt. Although “it’s the vitamin D” seemed like a reasonable hypothesis, I’ve been pretty careful not to just assume that—whenever I’ve written about this I’ve gone ahead and listed some of the other “active ingredients” that tend to come along with sun exposure—exercise, time in nature, etc. As I look into the matter more, I find there’s a growing body of evidence that sunlight itself does provide benefits, but it’s not just the UV light—the other frequencies of light are also actinic in all kinds of ways.

The UV light doesn’t just make vitamin D. It also has all sorts of other effects. In particular, it modulates your immune system in ways that reduce the risk of multiple sclerosis, and probably other autoimmune disorders and some cancers. It also reduces blood pressure. In mice it has been shown to limit diet-induced weight gain.

We’ve long known that blue light (especially, but not exclusively, a specific frequency of blue-green light absorbed by a pigment in the eye called melanopsin) was critical for establishing and maintaining an appropriate circadian rhythm. Very recently we’ve discovered that adipose tissue expresses the genes that produce the same pigment and use it to vary how the cell acts. In particular, after exposure to an amount of blue-green light that might shine through skin exposed to full sun, fat cells reduce the amount of fat they store, and also produce less leptin (a hormone that affects feelings of satiety).

As I discussed a few weeks ago, there’s been a lot of research on the effects of red and near-infrared light exposure. Here’s a page with links to a bunch of studies that suggest that red and near-infrared light boosts collagen synthesis, speeds healing of burns, incisions and broken bones, reduces inflammation, and generally reduces the effects of aging on your skin.

I guess that leaves us with orange and yellow light unaccounted for, but I don’t doubt that they’ll turn out to be actinic as well.

I have spent a lot of time following the latest research on all sorts of interventions to increase lifespan and healthspan. I am now ready to say that virtually all this time has been wasted.

I guess it hasn’t technically been wasted, in that I’ve come to understand the latest research, and that’s of some value. But when it comes to choosing interventions that might help me, it turns out there’s nothing new beyond the obvious healthy lifestyle recommendations of 20 or even 30 years ago.

There are a bunch of chemical interventions that are interesting—they have definitely been shown to increase healthspan and lifespan in animal models, and have had some very promising results in humans as well. However, it is becoming clear that virtually all of them are either exercise mimetics or fasting mimetics—drugs that activate (some of) the metabolic pathways activated by exercise or fasting.

From a public health perspective, perhaps this is of some interest. Given a population of sedentary people with poor diets it’s easy to foresee a mix of these drugs delaying mortality and morbidity—people will live longer, and during their extended lifespan they’ll have less disability, less illness, and require less medical care.

From my perspective though, it’s completely uninteresting. I would much rather just exercise than take a drug that provides a subset of the benefits of exercise. Similarly, I’d much rather just eat good food than take a drug that simulates some of the effects of doing so.

Do you want to live a long, healthy life? Here’s an plan for you:

That’s it. Unless you are sick with a diagnosed condition for which there is treatment, I very much doubt there is anything modern medicine—or even bleeding-edge longevity research—can do for you that you won’t get from this plan.

I’m sure my brother is very amused that it has taken me this long to come to this conclusion.