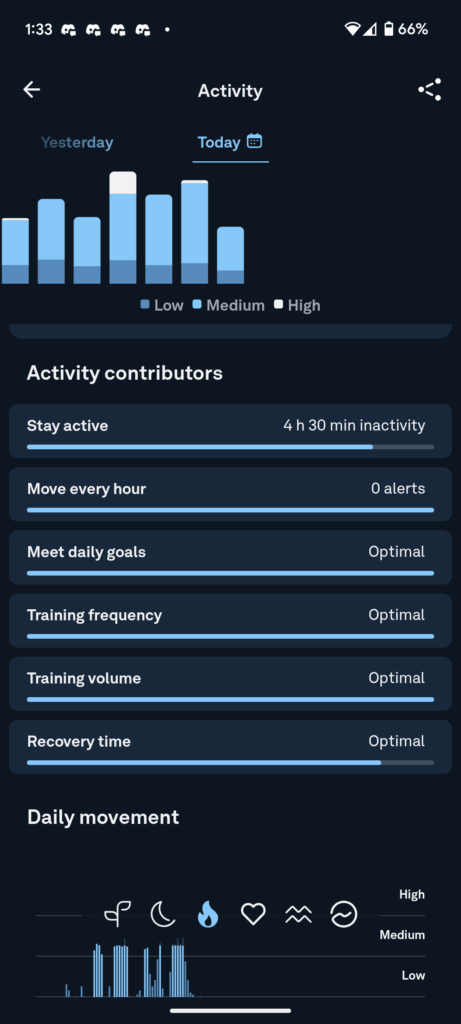

If you’ve been following me for any length of time, you know I’m big on metrics. It’s why I own both an Oura Ring and a Pixel watch. I am similarly interested in the annual blood work I get from my doctor’s office. That last though is often not quite as much or as often as I want, so I was very interested when Superpower reached out to offer me an extensive panel of blood work, if I’d post a review of their service.

This offer came at a particularly opportune time, as I’d been thinking of trying to get at least one specific test run ahead of my next physical. (I’d gotten a result that was slightly out-of-range on my creatinine test. This is common if you’re taking creatine, which I had been, but I still wanted to verify that it wasn’t indicative of a kidney problem. So, I’d gone off creatine, and wanted to re-run the test and be sure that my values had returned to normal.)

Getting a physical scheduled these days takes a ridiculous lead time, so it was going to be months before I got that blood work done. As I said, this made me want some other path to getting that test.

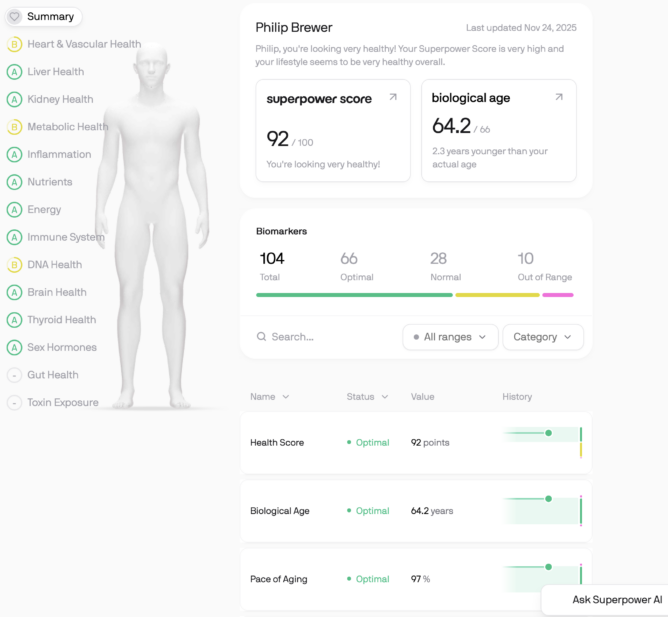

Enter Superpower, which is a way to get a vast suite of blood work done, but it’s much more than that. They have an AI trained on all these tests, with access to your results, that can integrate them together and answer questions about them. The answers are probably very similar to what your doctor could provide, except your doctor isn’t likely to have a couple of hours to go through your results line-by-line, the way I did last night with the Superpower AI.

You could get a reasonable read on any one of these markers just by googling the test name, but the Superpower AI has all your other results at its fingertips as well, so it can relate one value to another. For example, one of the blood tests measured my cortisol levels, and Superpower had this to say:

“Your cortisol level of 11.1 mcg/dL sits comfortably in the optimal physiologic range (10–18 mcg/dL), which suggests your adrenal function and stress response are well balanced.”

That’s roughly what you could get just by doing a google search on cortisol test and looking at the reference range. (Superpower is slightly better, because you won’t have to slog through the high values, the low values, the normal values, or the difference between the reference range and the optimal value.) But Superpower can do even better, because it has all your other data. For example, for me it goes on to say

- This level indicates your hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis is functioning normally—not underactive (as in adrenal fatigue or insufficiency) and not overproducing cortisol (as with chronic stress, inflammation, or metabolic strain).

- Given your low hs‑CRP (0.9 mg/L), balanced glucose (A1c 5.4%), and strong energy habits, your body is managing everyday physiological stressors efficiently.

- You also show good DHEA‑S (88 mcg/dL), suggesting adrenal reserve is intact and age‑appropriate. The cortisol‑to‑DHEA‑S ratio is within the healthy range, a good sign of adaptive—not excessive—stress output.

I knew nothing about DHEA‑S, so reading what the Superpower AI said about it was instructive.

There were dozens of other tests (I think 160 in the basic panel), so the part of my brain that wants all the metrics was very happy indeed. If you’re like me, and just want the metrics, Superpower seems great: Lots of metrics and a very useful AI tool to tell you what they mean.

If you’re not like me, and you’re just interested in improving your health and performance, the value of Superpower isn’t quite as clear, but I think there is some value:

- Every result that’s in the “optimal” range is one more thing to not worry about, and that’s useful.

- Every value that’s in the “good” range (normal but not optimal) is a thing you could work on to improve your health or performance, and the AI will make some suggestions for how you could work to optimize all your blood work.

- Every value that’s out of the reference range is, maybe, something you ought to talk to your doctor about.

That last is a bit uncertain. The doctors I’ve talked to over the years are pretty down on the idea of taking every test and then worrying about every value that’s out of the reference range. There are a few values (blood sugar, LDL cholesterol), where it’s both a clear sign that there’s something wrong that’s likely to lead to specific harms and there are practical treatments available that can reduce those harms. But just because a number is out of range isn’t much of a reason to do anything, unless there’s some symptom that’s plausibly related.

You almost certainly know what you ought to be doing to optimize your health. Eat food. Move a lot. Sleep well. (If not, read my post I’ve spent too much time thinking about longevity, which gives you a very slightly longer version of that same overview.)

Given that you know those things already, what would paying Superpower to run a bunch of blood tests do for your health and performance? That is: who is Superpower for?

First of all, it’s for people like me: People who just like having a bunch of metrics.

Second, it’s for people like me: People with a specific question to ask, like my question about creatinine levels.

Third, it’s for people who have trouble getting their doctor to go through all their test results with them. Of course any doctor who won’t go over any out-of-range results with you needs to be replaced. But ordinary blood work won’t even mention which of your results are in the reference range but outside the optimal range, and even a good doctor isn’t going to have time to go through those results and help you figure out how to improve them. The Superpower AI is a great tool for going through the normal-but-not-optimal results and coming up with a plan for optimizing your health.

Fourth, it’s for people who like the reassurance of being able to say, “Okay, I’ve got that one covered,” when one of the metrics is optimal, while being able to say, “Ah, but this other one could use a little more effort,” when one of the metrics is a little off. And, of course, there’s always the possibility that it’ll clue you in to something serious that you ought to take to your doctor.

So, how did I use it? Well, my creatinine levels had come back normal, so I’ve restarted creatine. My blood lipids are still a little off, even though I started a drug for that, so I have another thing to talk to my doctor about. Other than that, pretty much everything is normal, and most values are optimal, so I’m in that comfortable zone of feeling like I don’t have much to worry about.

How about the future? I just got the basic suite of blood work, and there are several options if I want to pay more money, and some of them are attractive.

For example, I’d be very interested to know about my magnesium levels. (Magnesium is very important in many cellular processes.) It’s not impossible to get enough magnesium from your diet—lots of foods have some magnesium in them—but there’s no one or two foods where you can just say, “Eat a couple of servings of this or that,” and you can be confident that you’ve got that base covered.

As another example, there are several B vitamins that need to be methylated to be turned into their active form, and people have a diversity of enzymes to do that, some of which are better than others. There are genetic tests to see if you have the gene for one of the good enzymes or one of the bad ones, but there are also tests to see if the vitamins in your blood are properly methylated, offered in the Methylation Specialty Panel. That’s another one that appeals to me.

I’ll consider those. If I decide to spring for them, I’ll follow up here in the future.

In the meantime, I’m pretty pleased with what I got: Something just for me.