The Winfield Village laundry room is open again, after having been closed for a week to put in new flooring.

The Winfield Village laundry room is open again, after having been closed for a week to put in new flooring.

We stocked our pantry yesterday, so we need not go out in the freezing rain.

Back in the day the telephone network was a regulated monopoly. As long as the phone company kept the regulator happy, they were permitted to earn a profit on their investment. This resulted in a couple of interesting effects.

First of all, the company was incentivized to invest more in infrastructure: The more they invested, the higher their profit (which was a regulated rate times the size of their investment). This is very different from an unregulated company, where investment is viewed as a cost.

Second, while keeping the regulator happy was always a complex dance, the regulator tended to focus on a few key metrics, one of which was network uptime. This incentivized the phone company to use that large infrastructure investment to produce a network of extreme reliability.

And that network was reliable. In my personal experience with wired phones in that era a wired phone always had service: For two decades as a youth I had literally 100% success picking up a phone and getting a dial tone. Likewise, calls did not drop. Service was rated in nines: 99.999% uptime was 5 nines, 99.9999% uptime was 6 nines.

Of course, that sort of reliability is impossible with cell phones. They move around. Worse yet, they go places where radio signals simply can’t reach.

Cell phone reliability is pretty darned good—let’s call it 98%, as long as you’re not trying to get service in places where nobody else cares if there’s service (the middle of the desert, the middle of the ocean, etc.). But people are not surprised when they find a spot where there’s no service, nor are they surprised if a call drops when elevator doors close or they drive into a tunnel.

This is not to say that cell phone service is bad. My point is simply this: To get the advantages of cell phones, people have accepted a drop in telephone service reliability from six nines down to less than two.

I think this is particularly of interest because I see a potential parallel with the power grid.

The big problem with solar and wind power is that they’re crappy at providing baseline power, for obvious reasons: nighttime, cloudy days, calm days, etc.

If you want a power grid to provide five or six nines of availability, you really need to have enough fossil fuel (or nuclear) generation capacity to provide a large fraction of your total power needs—at least 80%, probably more if you don’t have considerable diversity in your renewable sources (both diverse sources: solar and wind, and geographic diversity: the wind is always blowing somewhere and the sun shines different hours different places).

But just as people learned to get by with less than two nines of phone network reliability, people could certainly learn get by with a less reliable power grid as well.

Thinking of household use, there are certain things that really need fairly reliable power (refrigerator, freezer, furnace), but beyond those few things, we only require a high-availability grid because we’ve set things up with the expectation that it would be there.

Just two or three modest changes to the way we use power could easily accommodate a less-reliable grid.

The easiest one would be for each household to have a guaranteed level of power—enough to keep your food fresh, your pipes unfrozen, and a couple of lights turned on—and then make additional power available on an as-available basis. Alternatively, you could go with a market-based measure where power was cheap when it was plentiful and expensive when it was scarce. A third option would be to distribute the resiliency, with each household providing its own backup power storage or generation capability.

My point here is not to solve the issues for a smart grid, but just to make this point: For a big enough payoff—like the payoff of a internet-connected supercomputer that you can carry in your pocket—we would accept a considerable downgrade in reliability from our power grid.

The payoffs from renewable energy arguably are that big. (In particular, not rendering the planet uninhabitable for humans. But that’s a payoff that’s uncertain and diffuse, with the gains—especially the early gains—going to people other than the ones who need to make the sacrifices.) But there are payoffs to everybody: less particulates in the air, fewer pipeline and tanker spills, fewer truck and rail accidents hauling coal and oil through towns and cities, fewer worker deaths in the coal-mining and oil-drilling industries. And then there are the cost savings: Renewable power has the potential to be very cheap and very reliable in the out-years, once the infrastructure has earned out its initial capital costs.

It might well be worth getting past the idea that the power grid should provide near-perfect reliability, given the payoffs involved in accepting a bit less.

Last night the Urbana Park District hosted a winter solstice night hike at Meadowbrook Park, and Jackie and I had a great time walking with Savannah, the park district guide, and the nearly a dozen people who attended.

The winter solstice is always a hard day for me. The longest night should be the day things finally start to get better, but I have trouble finding solace in that truth. Making a bit of a ceremony of the solstice helps.

In years past—pretty much without even thinking about it—I have always fought against the gathering dark. My reaction to this tweet by Jonathan Mead is a good example.

The more you resist the seasons the more you’ll pay later. Sink into the darkness. There’s no better time than now to fully recharge.

I was having none of it:

“Good advice,” I say, vowing never to give in. I’ll gladly pay more later, when the light has returned. A lot more.

That particular reaction—so automatic, and so strong—prompted some thinking over the past year. Maybe there was something to the idea. Could it be that there’s a way to concede to the dark and cold without sinking into depression?

This winter I will experiment with that idea. I mean, it’s going to be cold and dark whether I rail against it or not. Maybe a bit of acceptance could help?

Savannah read a short text that advocated along these lines—something about “being where you are” on the winter solstice. [Updated 28 December 2016: I had emailed Savannah a link to this post, and she replied with the link to the text she had read from: Winter Solstice Traditions: Rituals for a Simple Celebration]

I’ll post more on this as winter progresses.

The night did not fully cooperate. The sky was overcast, which meant that we couldn’t see much in the way of planets or constellations. We didn’t hear any owls, despite Savannah’s best efforts to call to them, nor did we hear any coyotes. It wasn’t even as dark as it might have been—the low clouds caught and reflected the light pollution from Urbana and campus.

None of which meant the walk fell short of my hopes. Savannah talked about the history of Meadowbrook Park, and showed us several of their current projects—restoring native plants along Douglas Creek (Jackie helped with that one) and opening up some space along the Hickman Wildflower Walk. She talked about the Barred Owls in the woods to the west and the Great Horned Owls in the woods to the east. She talked about the few local species that hibernate, and compared them to the local species that instead engaged in winter sleeping. She took us to the Freyfogle Prairie Overlook and told us it was the highest point in the park—an amusing notion in a place so flat.

It was wonderful.

It was dark enough that I didn’t want to try to take pictures, so the pictures on this post are from earlier visits to Meadowbrook Park. The rabbit in the picture at the top is one of my favorite sculptures. This picture at the bottom, taken on one of our very long walks leading up to our big Kal-Haven trail hike, is from a spot quite close to the Freyfogle Prairie Overlook.

Jackie and I spent a few hours at the Urbana Park District’s Perkins Road Site, some land just behind the Urbana Dog Park that used to belong to the Sanitary District and was used for sludge ponds. The area is being restored as wet prairie.

Jackie and I joined a crew of about a dozen people cutting invasive bush honeysuckle and burning it.

I went to one or two stewardship workdays with my dad in Kalamazoo at preserves belonging to the Southwest Michigan Land Conservancy, but (probably just because of the details of what needed doing at those sites those days) didn’t come away with enough of a sense of accomplishment to prompt me to find similar opportunities here.

Since Jackie got involved with the Master Naturalists she’s been doing a lot of these, and I’ve joined her on several. We cut bush honeysuckle at Meadowbrook Park, and on another day gathered prairie seeds there. We pulled winter creeper at Weaver Park. And yesterday we were back to clearing bush honeysuckle—with the bonus that, because this site makes it difficult to haul things out, this time we got to burn it as well.

There’s an atavistic satisfaction that comes from playing with fire. Highly recommended. Don’t burn yourself.

As part of becoming a master naturalist, Jackie has been going on volunteer work days at local natural areas. A couple of times I’ve gone along as well, most recently on Saturday to Meadowbrook Park where we gathered prairie seeds.

Jackie is trying to learn to identify all the plants during all the seasons, so she made a point of gathering some of each of the prairie species that the organizers wanted.

I figured I’d just try and be productive, so I focused on a plant I knew I’d be able to identify, and just gathered baptisia aka wild indigo aka false indigo. Over the course of 90 minutes or so I manged to fill a big paper grocery bag about three-quarters full of seed pods. Apparently the crop is better this year than last year, when weevils consumed nearly every seed. (Although I did see a lot of weevils—kind of disturbing because their size and shape makes it easy to mistake them for ticks.)

It was pretty easy. I spotted a baptisia from the sidewalk and gathered its seeds (leaving about half behind, so that there will be some seeds to disperse naturally). Then I looked around, spotted another plant a few yards away, and moved to that one. They’re not very dense in the prairie, but I don’t think I ever harvested a plant without being able to spot at least one more to move to, and then another visible from that one.

The baptisia flowering stalks seemed to be a favorite of some medium-sized black wasp. I skipped those stalks. They are also a favorite of a large green and brown praying mantis, which blends in surprisingly well for such a large insect. I saw three of them, barely noticing two before I started harvesting, and not noticing the third until it scrambled off the stalk.

(That’s the same kind of mantis, although not taken in the prairie.)

These seeds are going to be used right in Meadowbrook Park. Over the winter, the mowed area in the southwest corner of the park will be turned into more prairie.

The workday shifts are nominally 2 hours, but they don’t work us very hard. Especially when we’re all off working in different locations, they start to try to get us rounded up again after just 90 minutes or so. (I think especially when it’s hot they keep the shifts short.)

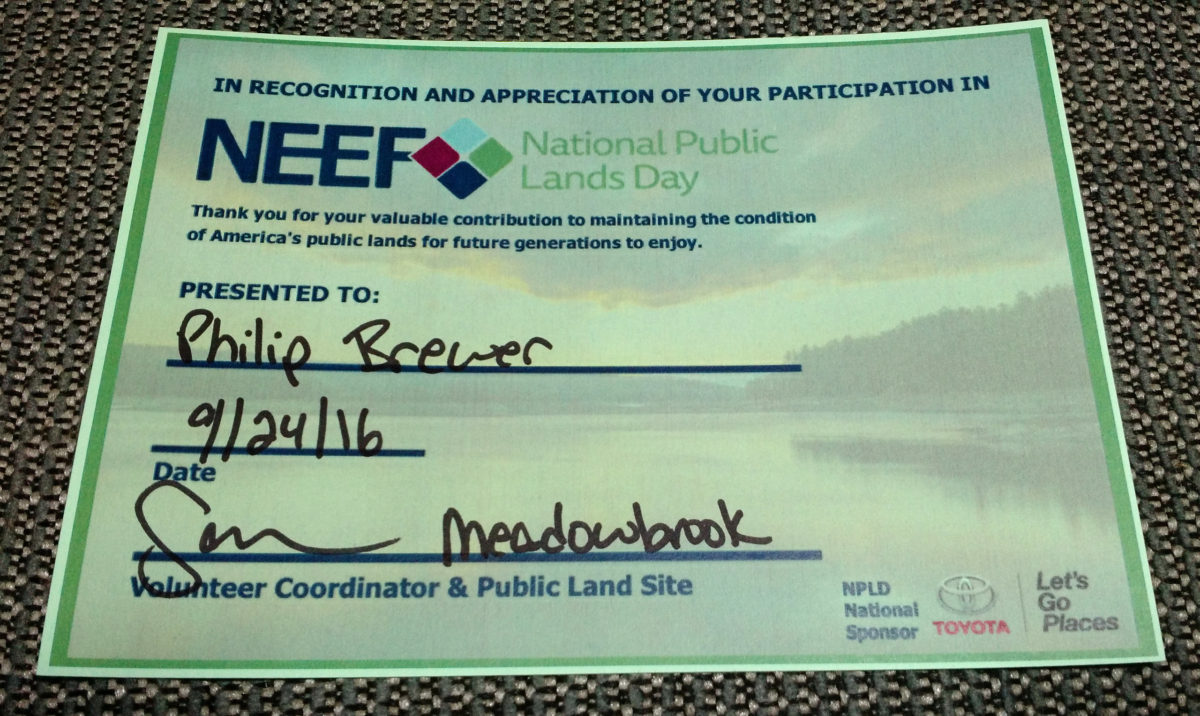

This particular work day was in celebration of National Public Lands Day, and while the workers refreshed ourselves with water, lemonade, and snacks back at the starting point, one of the organizers read an excerpt from a proclamation by Barack Obama in recognition of the day.

Then they gave anyone who wanted one a certificate recognizing our participation, and let us go.

Well shy of Shelobian proportions, but still I think the largest spider I’ve ever seen in the wild.

Spotted in the prairie, along the lower path. I put my hand in there for scale, but really didn’t want to get it quite close enough for that to work.

Updated to add: A bit of quick googling reveals that this is a yellow garden spider Argiope aurantia.

Everyone is welcome to join me and the folks from the tai chi groups I teach for free practice sessions this summer.

Everyone is welcome to join me and the folks from the tai chi groups I teach for free practice sessions this summer.

We’re planning to meet Monday-Wednesday-Friday 8:30–9:30 AM in Morrissey Park. (If we meet later it gets too hot before we’re done.)

These group practices sessions have no teacher or leader, so they’re free.

These sessions tend to be much like our usual classes:

This means that most of the hour is accessible to anybody, even complete beginners.

We’re starting Wednesday, June 1st. I’ve promised to show up for the first couple of sessions to help students from my beginner class get started on the longer form. (After that I’ll miss several sessions in a row because I’ll have family visiting, but there are lots of other friendly people there, many of whom know tai chi as well I do.)

Join us!

Jackie and I attended a tree identification workshop at Allerton Park yesterday.

Both my parents are naturalists, and my brother took some botany classes as part getting his PhD in science education, so they all know all the trees we’re likely to see in any of the places where we’ve ever lived. They routinely identify the trees for me when we’re walking. If I’d had any sense, I’d have learned all that stuff myself long ago.

Sadly, I have a lazy brain—the sort that figures that if other people will identify the trees for me, there’s no need for me to learn how to do it myself. So, I had to subject myself to this workshop to try and catch up.

It was a very well done workshop. We spent about half an hour going over basic terminology of tree characteristics—alternate versus opposite, simple versus compound, pinnate versus palmate, petioles versus petiolules—then we spent about three hours hiking through Allerton Park on the south side of the Sangamon River, before breaking for lunch. After lunch we spent another three hours hiking on the north side of the river, looking at the trees found over there.

We learned to identify maybe 30 species, with enough repetition of the more common species that we might actually be able to remember them.

It was good.

With all the time and effort I’ve been putting into fitness of late, I’ve been feeling just a little smug—I’m in so much better shape than I was nine or ten years ago. But this outing showed me that any such smugness is unjustified—everybody in our group of 20 or so, including some people older than Jackie and me, held up just fine to the rigors of five or six hours on our feet in the woods, some of it hiking off-trail. Jackie and I held up just fine too, but I was pretty tired at the end. (And managed to jam my ankle at some point, which wasn’t a problem during the event, but got sore in the night.)

It was a good reminder that endurance is a very complicated thing. Being in shape to walk briskly for 10 or 15 miles is not the same as being in shape to alternate walking and standing for the same number of hours. Adding effort in a mental dimension—trying to learn the trees, keeping an eye out for things like poison ivy, nettle, and tripping hazards—also makes things more taxing, something that’s easy to forget.

Now we need to get back to Allerton reasonably soon—before we forget everything—and see how many of those trees we can still identify.

The natural movement people I follow continue to broaden my perspective on what constitutes natural movement. Fairly recently, in her podcast, Katy Bowman pointed out that dilating and contracting the pupil of your eye is a natural movement.

Most people spend most of their time at just a few lighting levels—dark (however dark they keep the room they sleep in, which often isn’t very dark), medium (ordinary indoor light levels), and bright (ordinary outdoor light levels). Katy suggests that there may be some benefit in experiencing the whole range of light levels, from in-the-woods-at-night dark to full-sun-at-midday light—and most especially everywhere in between.

It’s an idea that appeals to me, and I’m inclined to copy her and go outdoors while it’s still dark, and take a walk during the time from just before dawn until just after sunrise.

Taking such an early morning walk would be a change to my daily routine, and whenever I think about adjusting my daily routine I like to compare it to that of Charles Darwin. He was so productive for such a long time, I figure his is a touchstone for a successful daily routine. So I went and checked and was very pleased to see that Darwin’s daily routine included a pre-breakfast walk of about 45 minutes.

I’d previously copied some elements from Darwin’s routine, but I hadn’t taken that one. I’ve been spending that time at the computer checking email, Facebook, and my RSS feeds, and chatting on-line with my brother. Those are all things that are probably worth doing, but maybe they don’t need to be the very first things I do in the morning.

I’ve been thinking about doing this for a while, but spring has been cold and damp and not really conducive to early morning walks.

This morning I took a test walk, strolling around Winfield Village and in the Lake Park Prairie Restoration in the half hour before sunrise. It was very pleasant.