The pale green lichen and the dark green moss are what caught my eye, and then I thought, “Oh, this might be worthy of a #thicktrunktuesday post!”

The pale green lichen and the dark green moss are what caught my eye, and then I thought, “Oh, this might be worthy of a #thicktrunktuesday post!”

“The research team discovered that 35 days of continuous exercise improved learning and memory deficits in the aging animals.”

Source: Optimal levels of exercise reverse cognitive decline in mice

I’m afraid I’m not up for 35 days of continuous exercise. Probably not even 35 hours.

I’m only rarely in shape to run 7+ miles, and even more rarely in shape to do it in the winter. 🏃🏻♂️

I spotted this toy in mile 4, and paused to get a photo.

On Friday I did a 4 mile run. 🏃🏻♂️ Around half way, a Red-tailed Hawk flew low over my head and struck at prey in the lawn across the street. Then, before I could get my phone out, flew up into a tree. You can see it there: the bird-shaped smudge about 2/3rds up.

Two writing sessions got me 1,067 words, and brings me to nine #amwriting days in a row. Now I need to rush through my morning exercises if I’m going to get in my workout in time to grill steaks for lunch. 🏋🏻♂️ ✍️

1,028 new words in my WIP, plus wrote out my critique for @limako’s latest story. Now time for my workout. #amwriting

Very occasionally I wish I were the sort of person who kept lists.

It’s most common that I regret not being a list-keeper when someone asks for book recommendations, especially when they want something in a particular scope—the 10 best books I read this year, or three books that I’ve given as gifts.

I’m always daunted by a request like that, because I have no idea what books I read this year.

Some of my tools—in particular, Amazon and my Kindle—do some amount of list-keeping for me. The public library could, but by default it doesn’t. (For very legitimate historical reasons, librarians worry about their patrons’ privacy, and since they don’t need to keep track of what books you’ve checked out once you’ve returned them, they default to forgetting about them.)

I played around with using a little toy tool called IndieBookClub, which posts the books you enter to your site, but it didn’t do most of the things you’d actually want such a tool to do (associate the books you’re meaning to read, books you’re reading, books you’ve read, and your thoughts about them), so I didn’t find it very useful.

Some people really enjoy the process of keeping lists, but that’s not me. Basically, I don’t want to keep lists, I sometimes want to have kept lists. I sometimes regret not having a list of something, but not in a way that makes me think I should start keeping such a list.

I do track some things—money, exercise, sleep—when experience has shown me that doing so is of great value, but in most areas of life I don’t keep track of anything at all.

Just today—after a year of having this post hanging around in my drafts folder—I saw plans for folks working on IndieWeb stuff to talk about how to do personal libraries in a way that would produce decentralized Goodreads-like functionality. That would really appeal to me.

In the meantime maybe I’ll look around at some list-keeping tools (or maybe start using a few pages in my bullet journal to keep track of books and other things worth tracking).

I’ll keep you posted. Maybe next year will be the year I keep a list of one more thing!

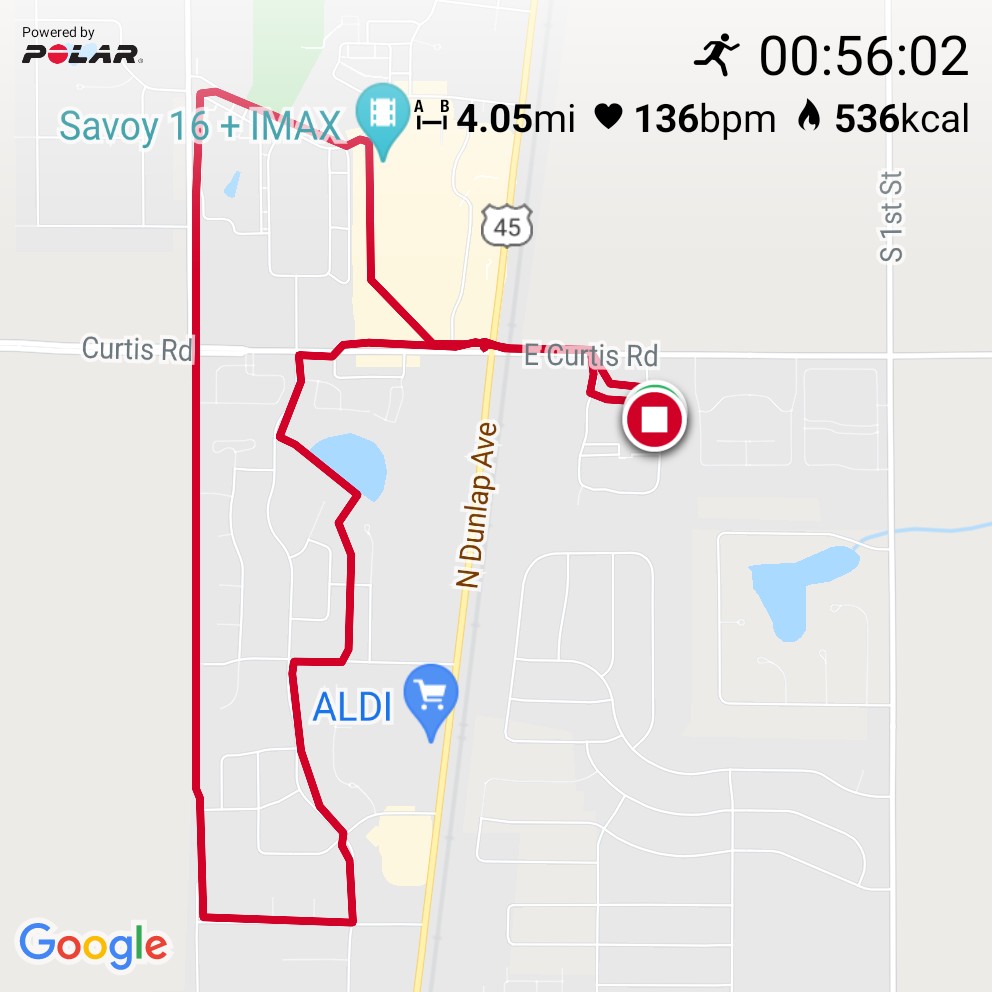

My “fast” run for this week was just an ordinary 4-mile run, except around the midpoint I set my interval timer and did all-out sprints 5 x 10″ with 50″ recovery. 🏃🏻♂️

This is the fourth week in a row where I actually did both my “long” run and my “fast” run—always my intention, but rarely achieved earlier in the year. 🏃🏻♂️

I started practicing tai chi in 2009 with a beginner course at OLLI (the OSHER Lifelong Learning Institute). I’d always been attracted to tai chi. I liked the way it looked—the slow, controlled movement. I was also interested in it as a martial art, and I liked the idea of “moving meditation.” Despite all that interest, I had not anticipated how transformative the practice would turn out to be.

Before I added the tai chi practice to my life, I was all about figuring out the “right” amount of exercise—and in particular, the minimum amount of running, lifting, walking, bicycling, stretching, etc. to become and remain fit enough to be healthy, comfortable, and capable of doing the things I wanted to be able to do.

Pretty quickly after I took up the practice, I found I was no longer worried about that. I found that my body actually knew what the right amount was, and that all I needed to do was move when I felt like moving—and make sure that my movement was diverse.

Because diversity was the key, I did a lot more than just tai chi. I continued running. I dabbled in parkour. I stepped up my lifting practice (and then shifted to mostly bodyweight training when the pandemic made gyms unavailable, and then continued with it because it seemed to work better). I went down a “natural movement” rabbit hole. I walked a lot.

In about 2012 or 2013 my tai chi instructor asked if anyone wanted to “assistant teach” the beginners class with him. I volunteered, and then did so. After six months or so he asked me to take over the evening class that he was teaching for people who couldn’t come to the early classes. I gradually started filling in for him on other classes as well.

In 2015 I formally took over as the tai chi instructor at the Savoy Rec Center. I really enjoyed teaching tai chi, although I found the constraints (having to show up at every class) a bit. . . constraining.

I did some tweaking around the edges (in particular, combining the Wednesday and Friday classes into a single Thursday class, so I could have a three-day weekend), which helped, but only so much.

Then a few weeks ago, the Rec Center wanted me to sign a new contract which would have required me to buy a new insurance policy, naming the Village of Savoy as an “additional insured.” I’m sure I could have done that—there are companies that sell insurance specifically for martial arts and fitness instructors. But as soon as I got set to research such policies, I realized that I really didn’t want to.

Instead, I wanted to retire.

I’d retired from my regular job years before, in 2007. And of course teaching tai chi four or five hours a week was in no way a career. The first few years I was teaching, I found the money I earned a nice supplement to our other retirement income. But with various improvements to our financial situation over the last few years, the money became pretty irrelevant, and the time constraints more. . . constraining. Especially with my parents facing various health challenges, I want to be able to go visit either one if that seems necessary, which has been difficult if I want to honor my obligation to my students.

So a few weeks ago I told the Rec Center and my students that I was retiring from teaching tai chi. My last classes were yesterday.

I’m sad not to be teaching my students any more, but delighted at losing the set of related constraints.

For years now, my students have been gathering in the park (Morrissey Park in Champaign, Illinois) during nice weather for informal group practice sessions, and I expect we’ll keep doing that. At any rate, I plan to be there, starting in the spring, practicing my tai chi. You are welcome to join us.