Having lunch in Monticello after hiking and running at Allerton Park. Despite what the glasses say we’re both drinking the Half Acre Daisy Cutter. 🏃

Having lunch in Monticello after hiking and running at Allerton Park. Despite what the glasses say we’re both drinking the Half Acre Daisy Cutter. 🏃

I wrote this a while ago, after seeing two articles in two days ragging on fitness tracking devices, and suggesting that they’re bad for you. Both articles warn against outsourcing your intuitive sense of “how you are” to some device. And, sure, I guess you can do that. But if you actually are doing that, I’d suggest that what you have isn’t a harmful device. What you have is a device disorder.

I was going to make an even stronger statement along these lines, comparing a device disorder to an eating disorder. I think the comparison is valid, even though, upon reflection, it weakens my argument. Sure, some people have an eating disorder. But anybody is likely to engage in disordered eating when they eat industrially produced edible food-like substances. Maybe that’s a fair comparison with industrially produced fitness-tracking devices. Unlike with industrial food though, I think the data from fitness trackers can be consumed safely.

“… sometimes I would wake up in the morning and check my app to see how I slept — instead of just taking a moment to notice that I was still tired…”

Source: Opinion | Even the Best Smartwatch Might Be Bad for Your Brain – The New York Times

I get this, because I joke about this myself. My brother will ask how I slept, and I’ll say, “I’m not sure—I haven’t checked with my Oura ring yet.” Or I’ll say something like, “My ring and I agree that I slept well last night!” But I’m just joking. I know how I slept, I know how recovered I am from the recent days’ activities, and how ready I am to take on a physical or mental challenge.

That doesn’t make the data from the Oura ring useless. My intuitive sense of how I am isn’t perfect. Many’s the time I’ve let wishful thinking convince me that I’m ready for a long run or a tough workout not because I really am, but because the weather is especially nice that day and the next few days are forecast to be cold or rainy. Or because I have some free time that day and the next few days are going to be busy. My Oura ring has been a useful counterbalance to that. If I had a hard lifting session yesterday, but I feel great today and my heart rate lowered early last night, maybe I am really ready for a long run today. On the other hand, if my heart rate took the whole night to get down to its minimum, and its minimum was higher than usual, that’s a good sign that I’m not fully recovered, even if I’m feeling pretty good.

If you have an eating disorder, do your best to avoid triggers that lead to disordered eating. Similarly, if you have a device disorder, it makes good sense to avoid using whatever sort of devices lead to disordered behavior. But that doesn’t make the devices bad, any more than eating disorders make food bad. But any particular device might be bad for you, just like any particular food might be bad for you. (And, I admit, industrially produced edible substances are probably bad for everybody.)

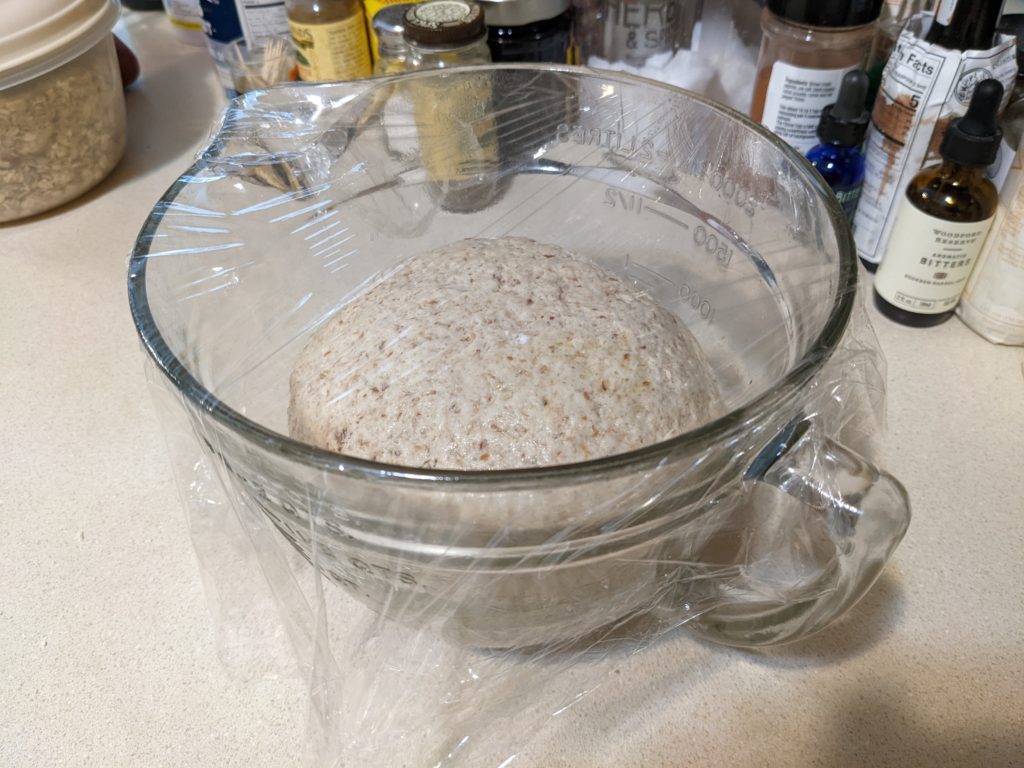

Today’s loaf has citric acid, acidic acid, salt, diastatic malt powder, boiled cider, olive oil, and honey. Oh, and it has oats, spelt, sprouted whole wheat, medium-grind whole wheat, barley, rye, einkorn, semolina, bread flour, and prairie gold flour. And, of course, it has Bubbles, our sourdough starter.

We’ve gotten Indian food a couple of times during the pandemic, but this is our first sit-down meal at one in two years, and we’re celebrating with Kingfishers. @jackieLbrewer

Sockeye salmon with the Great Salmon Rub from @Grovestone. Red onion and poblano pepper sauteed in olive oil. Extended Jam by @DESTIHLbrewery. Lovely wife @jackieLbrewer.

Very yummy, if I do say so myself.

Happy Valentine’s Day to my sweetie, @jackieLbrewer!

Soon to be flourless chocolate cake.

Loaf fresh out of the oven:

Today’s bread: 2 c Bubbles (our sourdough starter); ¼ tsp each salt, acidic acid, citric acid; ¾ tsp diastatic malt powder; 1 T olive oil; 2 T local wildflower honey; ⅓ c each rye, semolina, spelt, barley flour, quick oats; 1 c bread flour; 1⅓ c whole wheat.