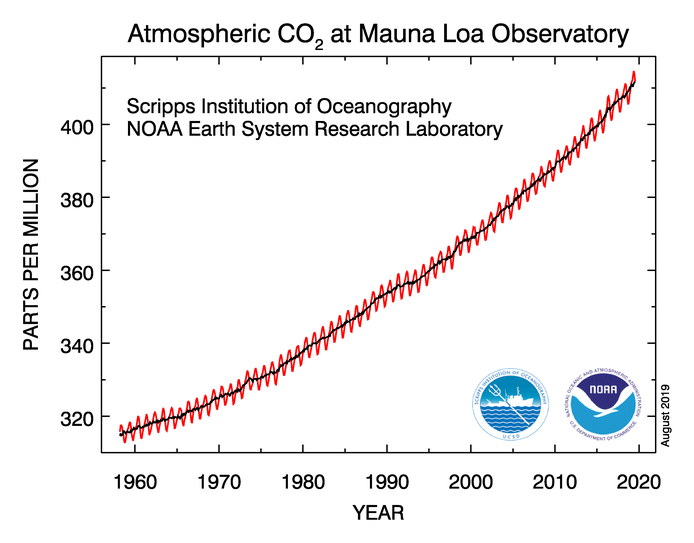

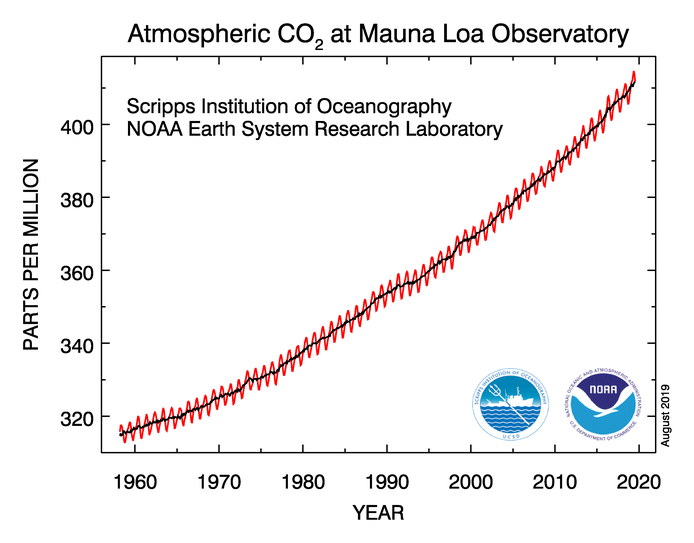

Interesting to me that the Great Recession doesn’t even show up as a blip on this graph.

Interesting to me that the Great Recession doesn’t even show up as a blip on this graph.

With no card number, CVV security code, expiration date or signature on the card, Apple Card is more secure than any other physical credit card.

Source: Apple Card launches today for all US customers – Apple

While @jackieLbrewer was working at the bakery there was a cash register glitch. For several days they took credit card payments on paper, writing the number down by hand, and then entering them manually at the end of the day.

Those customers would have been totally secure from being able to buy bread.

Very interesting and right up my alley: “fully automated luxury communism isn’t just science fiction: it’s a going concern with real evidence on the ground.” Via BoingBoing. h/t @limako

Cathy Reisenwitz is trying to reconcile her belief in the benefits of free enterprise with her growing realization that many industrial-produced edible substances are not healthy food. See: .

Personally, I do not find those ideas at odds: Corporations operating in a free market will make maximizing their profits their only goal.

Producing food that’s cheap to make and tastes great is the obvious way to maximize profits. Negative health effects that don’t show up for years (and don’t kill the customer for decades) are entirely consistent with the profit-maximizing goal of a corporation.

The health of their customers will only be prioritized to the extent that poisoning their customers isn’t profitable. (Sometimes not even then: See the multiple scandals related to Chinese companies adulterating milk and baby formula with melamine.)

A free society would make a priority of allowing each individual to choose what to eat based on their own values. One would assume that being as healthy as possible would be a priority for most individuals, but there are many stumbling blocks. (One of the biggest is that getting accurate information is hard in a world where corporations fund studies designed to produce and publish inaccurate results about the harms of eating too much sugar. Another is that food scientifically designed to be hyper-palatable is in fact so tasty as to be hard to resist, especially for children—and the tastes one forms in childhood influence one’s tastes as an adult.)

Free markets are the best mechanism we’ve found for optimal allocation of resources. But the market only allocates resources to achieve one set of goals (maximum profits) and ignores other goals. Maximum public health is one of the goals that a free market does not concern itself with.

As to the topic of the term “processed” food, I have found it useful to include a category of “minimally processed” food when thinking about what’s likely to be healthy.

Blame the bosses, not the robots, when your job gets automated away. ‘Robots’ Are Not ‘Coming for Your Job’—Management Is

Does money come with new-agey energy flows or emotions attached? For most of my life, I’d have said no (or more likely just rolled my eyes at the question). As you might expect from an economics major, I bought into a free-market model of how money worked.

Experiences over the course of my career, gradually convinced me that those ideas were . . . Well, not wrong exactly, but incomplete. I came to understand that money isn’t the kind of neutral object that it is in economic theory.

Ken Honda’s new book will let you skip over the 25 years of first-hand experience it took me to figure this out.

If you think money is a neutral, transactional artifact, then it just makes sense to earn as much as you can in the easiest ways possible. Because I was a software engineer whose career started in the early 1980s, it was pretty easy to find a job that paid well, and salaries grew rapidly, so I was doing just fine as an employee. There are certain things that come along with being an employee, the main one being that you’re supposed to do what your boss tells you to do.

I was okay with that. More okay than a lot of my coworkers, who objected when the boss wanted them to do something stupid or pointless.

My own attitude was always, “Yes, attending this pointless training class is a waste of time that I could be spending making our products better. But it’s easier than doing my regular work, and if my boss is willing to pay me a software engineer’s salary to do something easier than write software, I’m fine with that.”

The idea that I was fine with that turned out to be wrong. In fact, putting time and effort into doing the wrong thing is a soul-destroying activity. Getting paid a bunch of money for it doesn’t help. That money is, in Ken Honda’s terms, Unhappy Money.

Money that flows into (or out of) your life in a positive way is Happy Money—money that you receive (or give) as a gift, money that you earn by doing something useful (or spend to get something that you want or need). Unhappy Money is money lost or gained by theft or deceit, paid grudgingly by someone who feels cheated or taken advantage of—or, as in my own case, paid willingly, but paid to someone who doesn’t think what he’s doing to earn it is worth doing.

Honda’s thesis is that if you adjust your life around this idea—so that your own money flows are all Happy Money (and that you refrain from receiving or spending Unhappy Money)—your life will improve. My experience is that this is true.

If that insight is the key to the book, probably next most important is understanding that “There’s no peace to be found in always wanting more,” which is one of the points I tried to make when I was writing for Wise Bread.

To be honest, probably one reason I like the book so much is that a lot of the practical advice sounds a lot like what I talked about for years at Wise Bread. (For example that the strategy of just saving more quickly reaches limits in terms of its utility for making your family more secure.)

Much of the book is on the details of how to shift all aspects of your financial life toward Happy Money. There’s a long discourse on what he calls your “money blueprint”: The attitudes and practices passed down from parent to child (or rejections of those attitudes and practices), people’s basic personalities, and simple ignorance about how money works. A crappy money blueprint will predictably lead to people into cycles of Unhappy Money flows.

I’ve been interested in money for a long time, at least since sixth grade. Between studying economics in college, and embarking on an enduring interest in investing, I’m sure I’ve read hundreds of books on money. Among them, Happy Money: The Japanese Art of Making Peace with Your Money stands out.

Whenever I tweet about a company, I like to go ahead and tag the company in the tweet, so they can see what I’m saying about them. Besides that, I’ve a natural inclination toward brand loyalty (for companies whose products I like), so I like to keep up with what the company is doing, and twitter is a good way to do that. (Not nearly as good a way as an RSS feed, but that’s neither here nor there.)

The upshot is that I’m not infrequently searching for a company’s twitter handle—and just lately, I’m pretty often not finding one. More and more companies are limiting their social media presence to Facebook and Instagram—both of which are terrible choices.

Facebook is very bad. It tries to monetize passing on information! It deliberately holds back information that the company wants to share and that I want to see, specifically in order to pressure the company to pay up.

Instagram may be even worse. It is inherently about sharing pictures, whereas information is often best presented as text. Worse yet, it won’t share links, which is almost always what companies (should) want to do, if they’re trying to tell me about the sorts of things I want to hear about.

Twitter is a bad company that provides a service which is bad in many ways, but at least it will show me all the tweets of the company I’ve followed, tweets which can include text and links as well as pictures.

The photo at the top is of a donut I bought this morning at Industrial Donut—the latest company I noticed limiting its social media presence to Facebook and Instagram.

Why has the Fed been able to produce asset inflation but no price inflation for past 10 years? My guess: lack of union power and globalization are blunting transmission into wages and prices. But I don’t see an easy way to test that hypothesis.

In a recent speech, Fed chair Jerome Powell talked about “balance sheet normalization” in terms that strike me as essentially admitting that the Fed is a failure as a central bank.

Here’s the quote:

The crisis revealed that banks, especially the largest and most complex, faced much more liquidity risk than had previously been thought. Because of both new liquidity regulations and improved management, banks now hold much higher levels of high-quality liquid assets than before the crisis. Many banks choose to hold reserves as an important part of their strong liquidity positions.

Source: Federal Reserve Board – Monetary Policy: Normalization and the Road Ahead

Powell seems to be suggesting that banks have chosen to treat reserves in the same way a gold-standard bank treated specie: as cash on hand to meet demands from depositors who want their money back.

I call this a failure because a big part of the reason behind the creation of the Federal Reserve was that this system—where every bank held some gold—was clearly inadequate. Commentators at the time likened it to a fire protection district which, instead of having a fire engine, required every household to have one bucket of water on hand.

By having a large common stockpile of gold at the Federal Reserve, a loss of confidence in any one bank could be easily handled. Faced with a bank run, a solvent but illiquid bank would bring some assets (loans, bonds, bills, etc.) to the discount window and receive enough gold to handle redemption requests.

Powell is saying that banks seem to have decided that they can’t count on the Fed to discount their illiquid assets—a basic function of a central bank. Instead they’re choosing to stockpile large quantities of reserves exactly the way nervous banks stockpiled gold reserves in the pre-Fed days.

I’m sure this is based on the experience of the financial crisis, where many banks held a bare minimum of reserves and safe assets, choosing instead to invest the maximum amount in complex derivative instruments, which were highly profitable until they suddenly became worthless (or at least of dubious value).

But that just means that this is a double failure by the Fed:

By paying interest on these reserves, the Fed is enabling this behavior—solving the old problem that “gold in the vault pays no return.” But banks should be in the business of facilitating commerce in the economy, not the business of using their depositor’s money to score some free cash from the Fed.

I completely understand the Fed not wanting to again put itself in the position of having to decide what discount rate is the right one to apply to 3rd tranche mortgage-backed subprime paper. But a strategy of “just hold more reserves” is a pretty poor solution to the problem, for exactly the same reason that “just hold more gold” was a poor solution in the pre-Fed days.

I marvel that the 1% is being so indifferent to the large and widening leftward political shift in the U.S. and elsewhere. It seems to me they should have already started telling their politicians, “Give the poor folks 20% of what they want, quick! We need to nip this in the bud!”

Of course, maybe they’re right and I’m wrong.

They got away with globalization, after all. And then they got away with the financial crisis. And so far they’ve gotten away with Trump’s tax cut.

Now, I can understand the first two. Globalization, despite how it crushed many individuals, families, and communities, did make people better off on average. Having the average person end up better off makes a policy supportable at some level. I can see it providing enough political cover for them to get away with it. Who doesn’t like buying cheap crap at WalMart? Nobody but freaks and weirdos like me.

The financial crisis is harder to understand, which I think is due mainly to it being harder to understand. There was a real sense that our whole economy could implode—and it was a real sense because it was actually true. The technocrats managed to save the economy, so they get some credit for that. They did it in a way that crushed homeowners, which is bad. They did it in a way that subverted the rule of law, which is bad. And they did it in a way that crushed a whole generation, which is also bad. But they did save the economy.

But now we’ve got multiple cohorts of people who have already turned against the system. It’s no longer just the freaks and weirdos who care about their local community and the natural systems that support life. It’s no longer just former homeowners whose homes were seized to save the banks. It’s no longer just millennials who graduated into a job market so bad that they’re a decade behind their parents’ generation in things like family formation (and further than that in preparing to retire).

Now it’s basically everybody except the 1% who is being harmed, and they’re being harmed right now, every day.

The Trump tax cut is just a naked grab at wealth by the wealthy. It didn’t help anybody else. Trump’s tariffs aren’t even that—they don’t help anything but Trump’s ego.

I cannot imagine that any amount of voter suppression and gerrymandering—even with the structural anti-democratic features of our constitution—will keep the supermajority of people being harmed by our current system from making some major changes.

If the 1% had any sense they’d have thrown some bones to the people already. I can’t imagine that the smart ones haven’t figured this out already.

Sure, there are plenty of dumb ones who figure that they can build a survival bunker in Alaska or New Zealand and survive the ensuing revolution and climate catastrophe. But are they really all that dumb?

Evidence so far suggests they are.

Or maybe they’re right and I’m wrong.